I Can See Clearly Now

On learning to think about exhibitions, not just art

Hi everyone,

Recently I’ve been reading a new academic essay collection about what goes in to exhibition designs, but rather than review it like last week’s piece on upfront carbon, I thought I’d share a more personal story of my formative encounters with exhibitions and how they shaped my first forays as a museum curator. At the end, I share a few ideas for how you can get more out of the exhibitions you visit.

What shows have re-framed how you think about the form? Reply or add a comment at the bottom of the post and I’ll share more of my formative encounters.

Until next week,

Brian

PS—Last night, at a dinner celebrating a book I helped edit, a frequent reader asked: “Who’s paying for this newsletter?” So let me remind you that if you’re getting value from these weekly issues and have the means, you can support us by viewing this message in your browser and clicking either of the big green subscribe buttons. Your support helps us make Frontier Magazine available free to everyone.

Takeaways from this week’s issue

- Every museum exhibition tells several stories: that of the art or objects on view, of course, but also of the opportunities and limitations that arose when bringing everything together and arranging it.

- We enrich our experience of all spaces when we teach ourselves to see beyond or around the objects in an exhibition.

- As with architecture itself, exhibitions are the work of so many people who don’t receive credit. Recovering their stories can teach us more about how culture is produced and disseminated.

🔗️ Good links

- 🤳🏻🏛️ I return to Michael Sanchez’s prescient 2013 essay about how smartphones and networked technologies are changing exhibition design at least once a year

- 🏢👀 Buildings that caught my eye this week: T3 Collingwood, a 15-story mass-timber commercial tower by JCBA; no.555’s three-table restaurant in a renovated building in Chiba, Japan

- 👟👨🏾🎨 Five years ago this week, the MCA Chicago opened “Figures of Speech,” a survey of Virgil Abloh’s broad creative output

- 🚦🛣️ Two on traffic: on roundabouts in Prince Edward Island and using smartphone data to improve stoplights

- 🗽🗞️ This week I picked up the late Peter Schjeldahl’s The Art of Dying, a collection of his final reviews and essays published in the New Yorker. Essential. Buy it in the US or Canada.

- 📽️👨💼 The National Film Board of Canada has digitized and re-released Jack Long’s 1981 documentary about architect Arthur Erickson

Title again

I was lucky to encounter artist and writer Brian O’Doherty’s influential book Inside the White Cube not long after I began regularly visiting galleries and museums. On its second page, he writes, “We have now reached a point”—now being the mid-1970s—“where we see not the art but the space first. […] An image comes to mind of a white, ideal space that, more than any single picture, may be the archetypal image of twentieth-century art.” His slim, provocative volume revealed to me many of the political and social implications of the “white cubes” I was just becoming familiar with. The book taught me that such spaces are anything but neutral containers.

Other historians have followed in O’Brien’s footsteps, including Charlotte Klonk, whose 2009 book Spaces of Experience described two centuries of developments that led to the white cube. Less scholarly attention has been paid, however, to the process of designing the exhibitions that fill those spaces. When I began organizing art-museum exhibitions about a decade ago, most of the ideas I brought to designing them came not from critical texts like O’Brien’s but from countless hours spent in galleries.

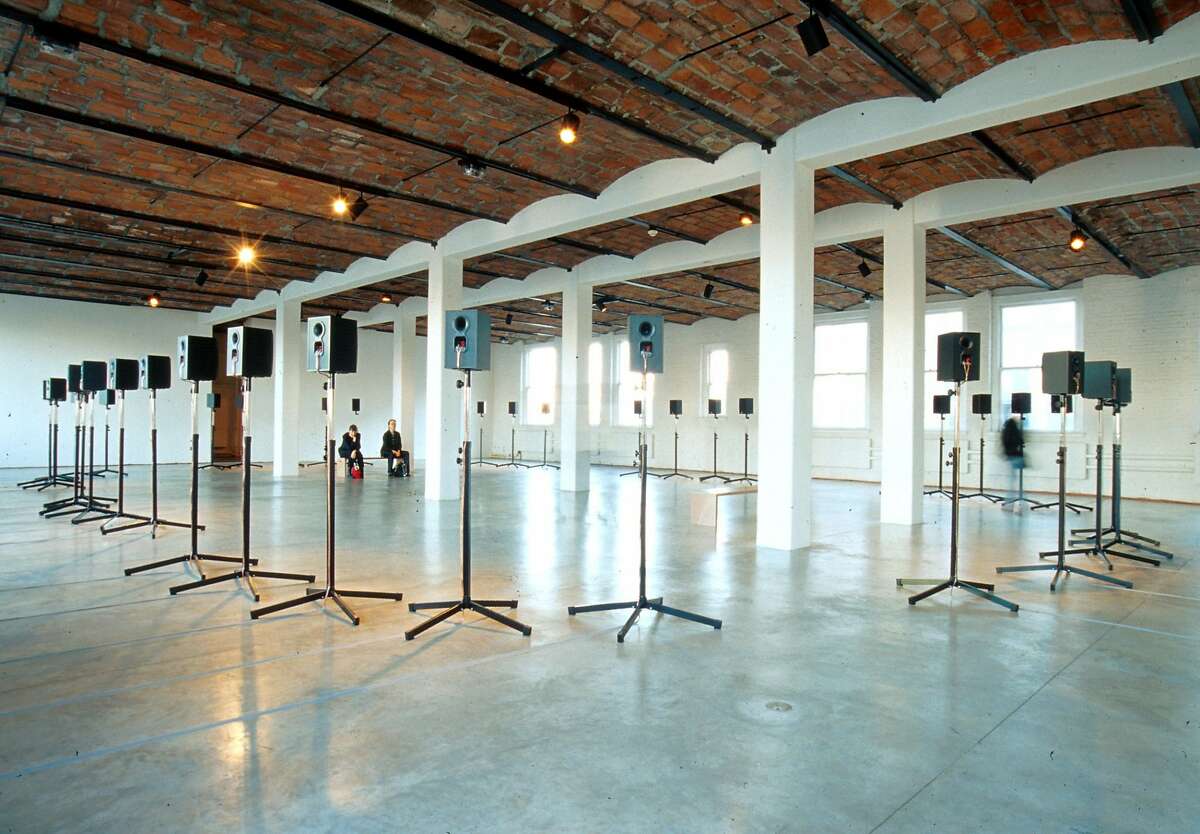

Sometimes the lesson arose from the cumulative effect of experiencing the same art in a variety of spaces. As an intern at P.S.1 in the fall of 2001, I spent countless hours in the large, barrel-vaulted room where Janet Cardiff and George Bures-Miller’s The Forty Part Motet played on an endless loop. Surrounded by freestanding speakers, each carrying the voice of a different Salisbury Cathedral Choir member, I had quasi-religious experiences that have made the installation one of the most popular artworks of this century. That popularity means it has been exhibited widely, and comparing my experiences with The Forty Part Motet again at London’s Whitechapel Gallery in 2003, at P.S.1 again in 2012, at the Met’s Cloisters in 2013, and at the National Gallery of Canada several times has taught me as much about those varied spaces as it has deepened my experience of Cardiff and Bures-Miller’s artwork.

But I’ve also benefited from artists who deliberately make the exhibition space an artwork, or part of the artwork. One transformative encounter was with photographer Christopher Williams’s 2014 exhibition The Production Line of Happiness. Its first presentation, at the Art Institute of Chicago, included radical gestures, such as hanging only one small picture in a ~1,500-square-foot gallery or creating a forest of uniformly sized walls that reveal the method of their construction. Later that year, at MOMA, some of the walls from Chicago were laid on the floor; other walls featured blown-up pages from the exhibition catalog; and one was made of cinder blocks, in reference to mid-century displays at The Whitechapel, its subsequent venue. As Williams put it in an interview, “Each of the three venues has a similar checklist, but the relation between the pictures, their organization, and the architectural frame changes with each venue.”

The Production Line of Happiness refreshed my appreciation O’Brien’s lessons at just the right moment. I had just joined the staff of a museum as its photography curator and was in the process of putting together my first large exhibition. The many collaborations required by that process—with the exhibiting artists and their galleries, with the museum’s internal design and education teams, with external fabricators, with my colleagues keeping the budget and authorizing expenditures—underscored Williams’s lessons: that all exhibition designs are contingent rather than predestined.

Yet when that exhibition was ready, I was the one giving the opening-night speech and the weekend tours. So much of that additional labor became obscured. A new academic volume edited by Kate Guy, Hajra Williams, and Claire Wintle, Histories of Exhibition Design in the Museum, argues for closer attention to those obscured histories. As they note in their introduction, “despite their centrality, the everyday processes and practices of exhibition design that shape the museum often go undocumented and even unnoticed.” On why that may be, they add, “exhibitions are challenging objects to reconstruct and research; they are multi-authored, complex tools of expression, iterative and experimental, and ephemeral in their nature.”

You could argue that difficulty is intensified by our recent predilection for showy museum buildings. Perhaps since the opening of Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, in 1997, our bias has been toward thinking about the exterior forms of these buildings. (Or, as with Studio Gang’s new American Museum of Natural History, show-stopping atria that double as rental spaces.) But our most intimate encounters occur with exhibitions in their galleries, and the design, sequencing, and lighting of those spaces is as carefully thought-through as are the buildings themselves. And unlike the buildings, exhibitions change frequently: you can see a new one every few months.

For those of you interested in deepening your experiences of built environments, in enhancing your thinking about how the stories these spaces convey are created, consider my technique for visiting any exhibition I want to engage with deeply. First: don’t read the wall labels! I go through a show reading nothing, just gathering sensory impressions and seeing what the art and layout tell me. Second: turn around when you reach the end and return to the beginning, against the flow of traffic, thinking both about what you saw and what you can glean from the layout decisions. Third: follow the prescribed path again, this time reading most if not all of the labels and squaring your thoughts with the curator’s.

If you try this, let know what you think!