A Brand Is Not a Tree

What Brand Builders Can Learn from City Planning

In 1965, Christopher Alexander wrote what went on to become an iconic essay in the world of architecture. “A City Is Not a Tree” was first published in Architectural Forum and eventually ended up in his classic 1975 book A Pattern Language. In the essay, Alexander criticizes the modernist movement’s tendency toward city plans whose trunk → branch → twig hierarchy resembled highly rational grid structures. For him, this way of planning missed the nuance, depth, and overlap that define thriving cities. He argued for the concept of the semi-lattice, a construct that enables rich, overlapping, and evolving systems.

A mailbox, for example, means different things to different people. A person delivering mail sees an object they use to complete their job. A person expecting a letter might see a way to connect with a loved one on the other side of the world. A street cleaner might see an obstacle to be avoided. A dog might see a place of relief.

All of these interpretations are true, and the tree structures that defined modernist urban design (and classical information-organization systems) did not lend themselves to overlapping interpretations.

Superlinear Cities

Contemporary interpretations of cities include the idea of human friction. Jane Jacobs described how “cities have the capability of providing something for everybody, only because, and only when, they are created by everybody.” And it’s the encounters between strangers, the mixed uses of spaces, and the overlapping flows of people that create vibrancy. More recently, theoretical physicist Geoffrey West, of the Santa Fe Institute, proposed that cities have a metabolic rate. They are superlinear systems in that, as population increases, so does productivity and innovation, at an accelerating rate. He goes so far as demonstrating that when you know the speed of an individual’s footfall in a city, you can extrapolate to the number of patents and libraries the city has, among other things.

How fast people walk, in other words, can be a visible indicator of underlying urban dynamics—especially those related to scale, energy, productivity, and social behaviour. As cities grow, so does the average walking speed. You don’t need to tell a person from any small town that people in Toronto, or any big city, walk faster. According to this theory of superlinear scaling, faster walking speed suggests higher metabolic and cognitive activity and the urgency, density of interactions, and compression of time that is characteristic of a big city.

A City Is Not a Logo

Planners and developers, to varying degrees, build with a goal of creating vibrant urban spaces. They build with physical materials, with atoms. Brand builders are building physical things as well, but they are also building ideas and mindsets, physical and digital and conceptual worlds, with bits as well as atoms. This intersection between atoms and bits is the opportunity for both brand builders as well as planners and developers. Neither want to build one-dimensional experiences. Both are trying to create vibrant worlds. Each can learn from the other.

A Logo Is Not a City

Just as the complex richness of a city isn’t encapsulated by its skyline or its flag, the potential richness of a brand should not be limited to its logo. For brand builders, a great brand, like a great city, is not a finished thing.

Brand strategy often relies on literary ideas. Concepts like the hero’s journey or the brand manifesto help to both create and guide a brand. But these metaphors are brittle. Campaigns fade. Logos change. Enduring brands endure not because of a single narrative arc, but because they are built like cities: complex, layered, resilient, and constantly evolving. Traditional branding and brand managers fight for a fixed, consistent identity across all “touch points.” But this approach assumes that the brand exists in a static world. The brand is “performed” and the audience is … well, the audience. They watch.

That world is gone.

Today’s audiences are not passive. They remix, respond, and reinterpret. Brands live across unpredictable environments: owned media, earned media, dark social, physical experiences, decentralized networks, and AI models. Trying to tightly control a brand in this new world is like trying to control how people move through a city using only billboards. Brands need to create ecosystems where meaning can emerge. They should be designed with intention but be open to variation, to life. Great urban environments support cross-pollination and engagement—and so should great brands.

If you think about the great cities of the world, each is distinct. Tokyo, Copenhagen, or Mexico City all evoke feelings that do not come from a single symbol or slogan. Those feelings are created in the layers that make up the city: language, signage, infrastructure, rhythm, the way light shines through the leaves on a narrow side street. Each city is greater than its “brand”; it is its experience.

Compare that way of thinking with how many companies approach brand: logo, font, cheeky tone of voice. It’s like trying to brand a city with a postcard. Instead, today, a strong brand, like an iconic city, earns its identity through much more than a visual-identity toolkit.

Take Parade, the Gen Z underwear brand. Founders Cami Téllez and Jack DeFuria built a fashion company that doesn’t behave like a traditional fashion company. They operate more like a queer-inclusive cultural district. Sex positivity, sustainability, body diversity, pop art, and political activism all intersect in its world. The aesthetic is fluid and the tone is playful but also radical, and the product itself connects to a much bigger social conversation than underwear.

It’s not a brand built on a single framework. It’s a dynamic neighbourhood where identity, values, and styles clash and mix and remix. Its urban plan is not top-down. It’s not a tree. It’s deeply embedded in the feedback it gets from its community and the cultural loops it creates through its activities. It doesn’t tidy up contradictions. It knows that contradiction is at the heart of what makes it thrive.

Desire Lines

Urban planners refer to the paths people carve across lawns and public spaces as desire lines. A smart city planner watches these lines and responds by turning them into real paths.

The same applies to brands. Users will always appropriate the brand in ways you didn’t anticipate. They’ll meme it, critique it, mangle it, and love it for the wrong reasons. Smart brands do not fight that. They see them as opportunities. They observe, adapt, and co-design with their fans.

Duolingo leaned into the internet’s obsession with its passive-aggressive owl mascot. Rather than shutting it down, the brand embraced the chaos. Today, Duo appears in viral TikToks, weird fan fiction, and even parody ads, and the company got so carried away they killed it. Or did they?

That desire line became its main path.

Density, Mixed Use, and Adaptive Reuse

The best cities aren’t neatly ordered, they’re layered. There might be an apartment above a bakery next to a gallery inside a former factory. These unexpected overlaps create richness and allow the past to meet the present and support unexpected futures. The same principle applies to modern brands.

When MSCHF collaborated with Crocs, they created a viral shoe phenomenon. Every product they make is an overlap of culture, fashion, and cultural critique. And despite the diversity and dissonance, it all feels like the same city.

Great brands not only embrace contradiction, they invite it—and understand the reality that people will do what they want and interpret their products how they choose.

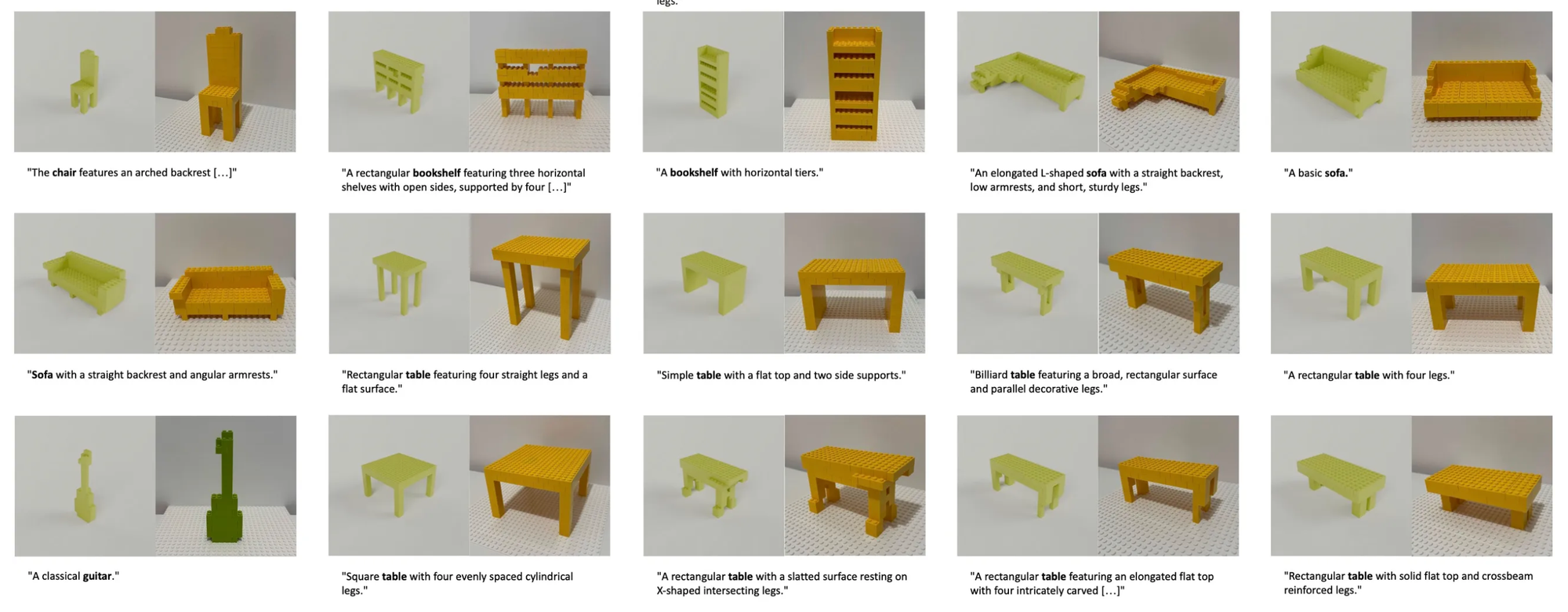

Lego’s brand resurgence is an example of adaptive reuse. It opened its platform far beyond its “core demographic” and invited architects, artists, and, well, everyone to submit kit ideas—even AI-generated ones. It treated its original product like an old abandoned building with massive potential for a new use. It invited new people and their inventive energy to reimagine what it could be.

Building for People and Not PowerPoint

Many brand systems, especially for smaller companies or those that are not direct-to-consumer, are designed primarily for pitch decks. They can look great as a set of brand guidelines or slide templates, but they collapse when used in the real world.

Cities don’t have the luxury of living in such neat and controlled environments. A beautiful master plan means nothing if the city doesn’t work for its residents and visitors. There are endless examples of brands that fall apart when put into practice.

Instead, the sensory, emotional, and communal human experience must be central to branding. It’s not just about what a brand says, it’s also how it feels to live in it. What does it feel like to move through your brand city? What friction points to people hit? Where are the moments of joy?

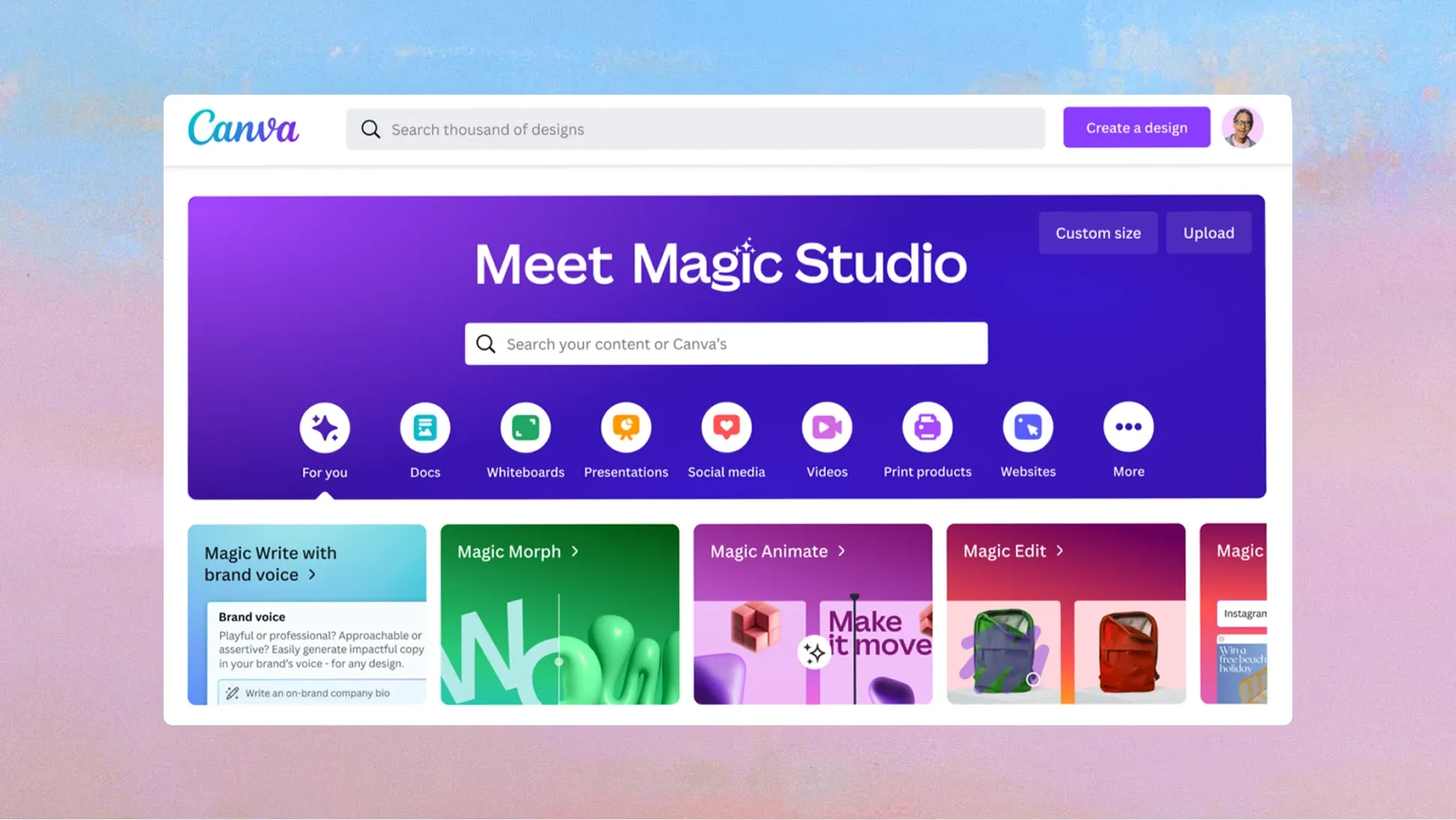

Canva, the design platform, has built an entire “city” for people who didn’t think they were designers. Every single touch point, from onboarding to templates to social content, is optimized for ease and enjoyment. While not necessarily the most exciting brand in the visual sense, it’s livable, like a great city. And that’s why people keep coming back.

Out the Window

Urbanists know that cities are never finished. They grow, decay, and regenerate over centuries. They hold collective memory, survive extreme crises, and adapt. They outlast individual leaders and strategic plans.

Shouldn’t brands do the same thing?

Many organizations today think about their brands like monuments: static and unchanging. The only way to get a better viewpoint is to throw that mindset out the window. The next generation of brand strategy will come less from advertising and more from a practice inspired by living and urban systems like ecology, urban planning, and participatory design. The market will reward brands that plan for evolution and not just impressions. It will reward those who think about brands in the way urban planners think about cities.

If you’re building a brand, ask yourself: Are you building a monument? Or are you building a place that people want to live?