After-School Special

On learning in—and especially beyond—the college classroom

Hi everyone,

At our normal publication hour I was participating in a lively panel discussion on architecture and design publishing hosted by DesignTO. Thanks to those of you who attended, and welcome to the many new subscribers who arrived this past week. Below is the second part of our “back-to school special”: a reflection on Wesleyan University president Michael S. Roth’s new book about being a student.

I finished my formal education more than a decade ago, but I feel like I’m learning as much now as ever. In what ways are you still a student? Hit reply or comment below to tell me, and what you share will inform what we choose to cover in future issues. See you next Wednesday at our appointed hour.

Love all ways,

Brian

After-School Special

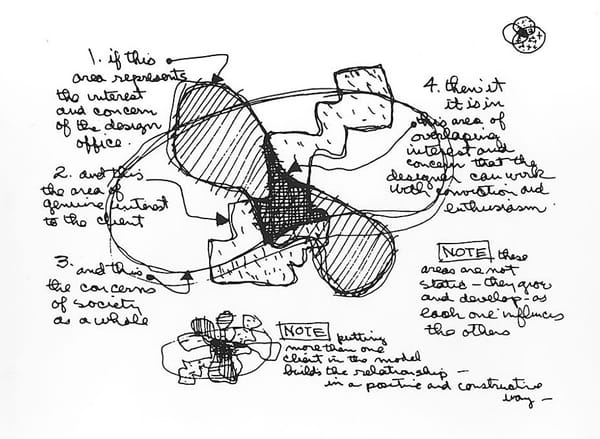

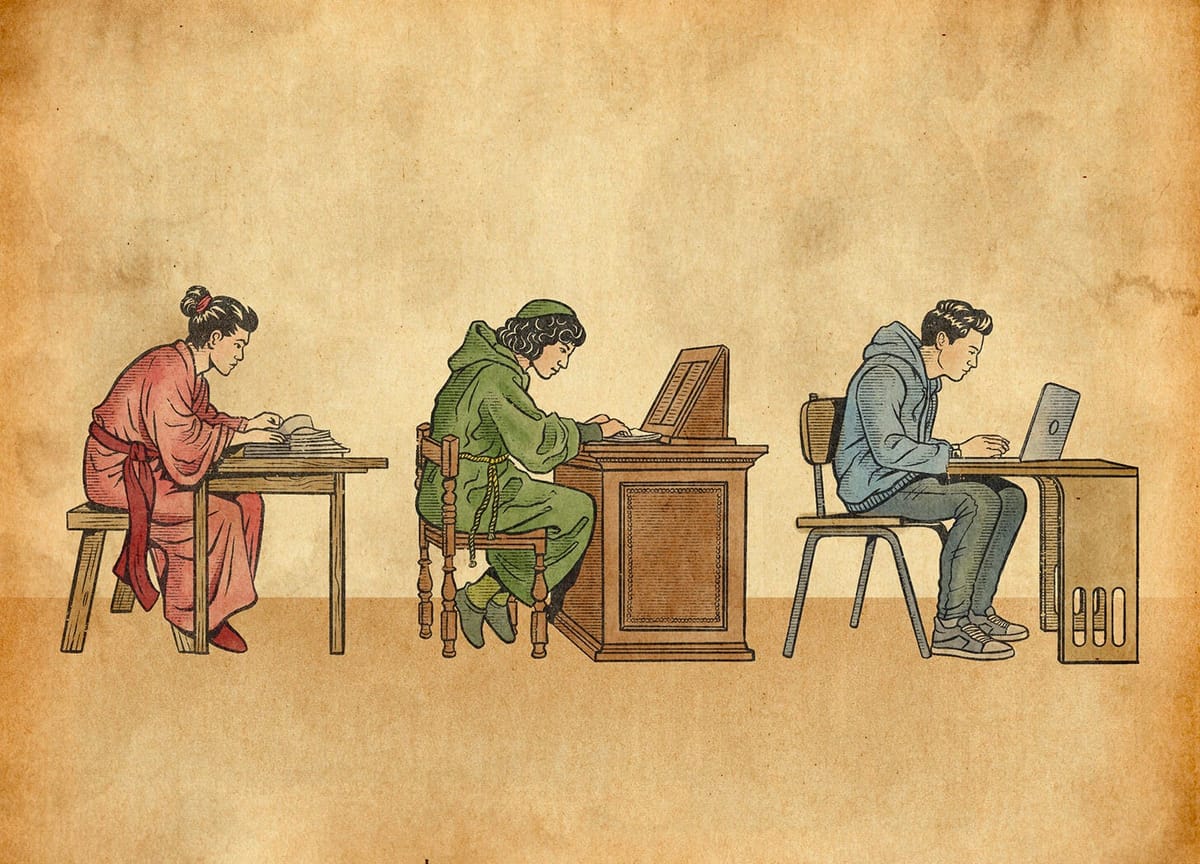

In The Student: A Short History (buy in CA, US), Michael S. Roth narrates how the definition of student has changed through the centuries, from those who gravitated to “iconic” ancient teachers Confucius, Socrates, and Jesus to today’s teens choosing a university. It is a malleable concept, ranging from followers and disciples in ancient times to Medieval apprentices and rowdy nineteenth-century “college men.” This wandering path, Roth suggests, heads off in an irreversible new direction with the words of philosopher Immanuel Kant. The first line of Kant’s essay “An Answer to the Question: What Is Enlightenment?” reads: “Enlightenment is man’s emergence from his self-incurred immaturity.” As Roth adds, “This is the clarion call in the development of the modern idea of the student: someone in the process of learning to think for oneself.”

Roth helpfully anchors his story in the biographies and words of individuals, from Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Thomas Jefferson to lesser-known figures like Charles Rollin, a Catholic priest and rector at the Sorbonne in Paris, the Prussian education minister Wilhelm von Humboldt, and American academic James Morgan Hart. Students continually push for scholarly autonomy, the ability to use their status as students to go beyond premodern obligations to God, family, and community. They want to engage in inquiry for its own sake, for their development as whole beings. Roth acknowledges this push was halting and uneven: “The direct pathway to freedom was education, and nothing made that more apparent than attempts to block it.” This was especially true for women and for slaves, as the references to Mary Wollstonecraft and W.E.B Du Bois make clear.

Nonetheless, this is a story of progress: “With freedom we can be students, and as students, we expand the realm of freedom.” Roth is a suave commentator on philosophy and literature, and anchoring his story in others’ words makes for an entertaining read—and gives the dedicated independent learner a rich bibliography to explore. Yet his scope narrows as he marches toward the present, zeroing in first on higher education, then higher education in the United States.

At one point Roth writes, “The focus on exclusive schools distorts our picture of what it means to be a college student.” I am as deeply committed to the ideas of liberal education as Roth, and believe as strongly in its personal, social, cultural, and political benefits. I thrilled to the miniature disquisition on teaching in the final chapter, which moves from John Dewey and Paulo Freire to a paragraph that references Friedrich Nietzsche, John Baldessari (!), and William James.

Yet as his story narrowed, I began reflecting upon my own formal education, which through great fortune included stints at both private and public schools and universities in the US. I’m grateful for those experiences, but, looking back on them from the vantage point of middle age, I realize that the bulk of my learning didn’t happen while a college (or graduate) student.

Though no one would have described me as a “student” of its bands and zines, I learned as much from participating in Chicago’s punk scene during high school as I did in the core arts-and-sciences curriculum during my undergraduate years. Though there was no syllabus, I have learned as much from sharing my writing online—and hearing back from strangers about it—as I did from certain of my professors in graduate school. And so I began to ask myself, while reading The Student: how can we ensure our understanding of the term incorporates such experiences?

Roth helpfully mentions what he calls, at one point, “lateral learning”—the idea that students learn from each other as much or more as they learn from their teachers. Now I want a whole other history of that kind of learning-through-mutual-support, an update to and expansion of Joseph Kett’s 1994 book The Pursuit of Knowledge Under Difficulties. This is why I prefaced today’s newsletter with one last week focused on two experimental educational initiatives, and why I continually seek out self-organized and non-accredited educational projects. At one point Roth writes, “The [public] focus on exclusive schools distorts our picture of what it means to be a college student.” The same is true of a narrow focus on college in defining what it means to be a student today. In most people’s lives, if they have the good fortune to attend a university, those years are their own “short history.” There are so many more ways to be a student, and I look forward to exploring them with you.

🔗 Good links

- 🤔 Many of the links above are to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, which is an autodidact’s dream: a massive, continually updated, and freely available archive of expert philosophical knowledge

- 🎳 “It felt like our clubhouse, like a punk-rock Cheers.” WBEZ public radio recently produced a half-hour audio documentary about The Fireside Bowl, the punk venue mentioned above

- 🏛️ “American museum educators are trying a more playful approach”

- 🤳🏻 Thanks to Jason Kottke for resurfacing this perfectly expressed cultural-intellectual mashup from 2017, which I had forgotten about: Steve Reich Is Calling