Bad Moon Rising

On The Sphere, a new building in Las Vegas that’s empty by design

Hi everyone,

Quick housekeeping note: Our editorial partnership with The Bentway continues. Yesterday we published my interview with urban ecologist Matthew Gandy, which touches on the ecology of concrete, engineered versus spontaneous landscapes, and the politics of design language. Find that story and dive deeper into the series on this page. Thanks!

About ten days ago, short videos of a giant glowing basketball, seen through the dashboard of a car driving up a street, appeared all over my Twitter feed. The ball towers over the mid-rise apartment buildings in the middle distance, a surreal apparition seemingly lifted from Blade Runner 2049. I wondered, Is this some weird AI trick?

A little sleuthing and I realized that no, it’s not a trick. In 2015, nepo-baby billionaire James L. Dolan got the blues after selling Cablevision, the company his father built, to a French telecom giant and finding his New York Knicks on the path to another losing season. To lift his spirits, Dolan, whose companies own other sports teams as well as Madison Square Garden and Radio City Music Hall, decided to “reinvent live entertainment.”

As Rolling Stone senior writer Andy Greene noted, “Without giving any thought to what was technologically feasible, Dolan drew a sketch of an enormous geometric structure, essentially a spherical IMAX theater on steroids. Its central purpose would be to house arena-size concerts…. ‘We had literally no idea how we were going to do it,’ says [MSG Ventures CEO David] Dibble. ‘We had no staff. It was just Jim Dolan and me.’”

Eight years and $2.3 billion dollars after Dolan drew a circle on the proverbial napkin, this giant basketball was the first sponsored use of The MSG Sphere at The Venetian, an eighteen-thousand-seat arena in Las Vegas covered, inside and out, with super-high-resolution LED screens. The building does not officially open until late September but had already been turned into an advertisement for the NBA’s Summer League.

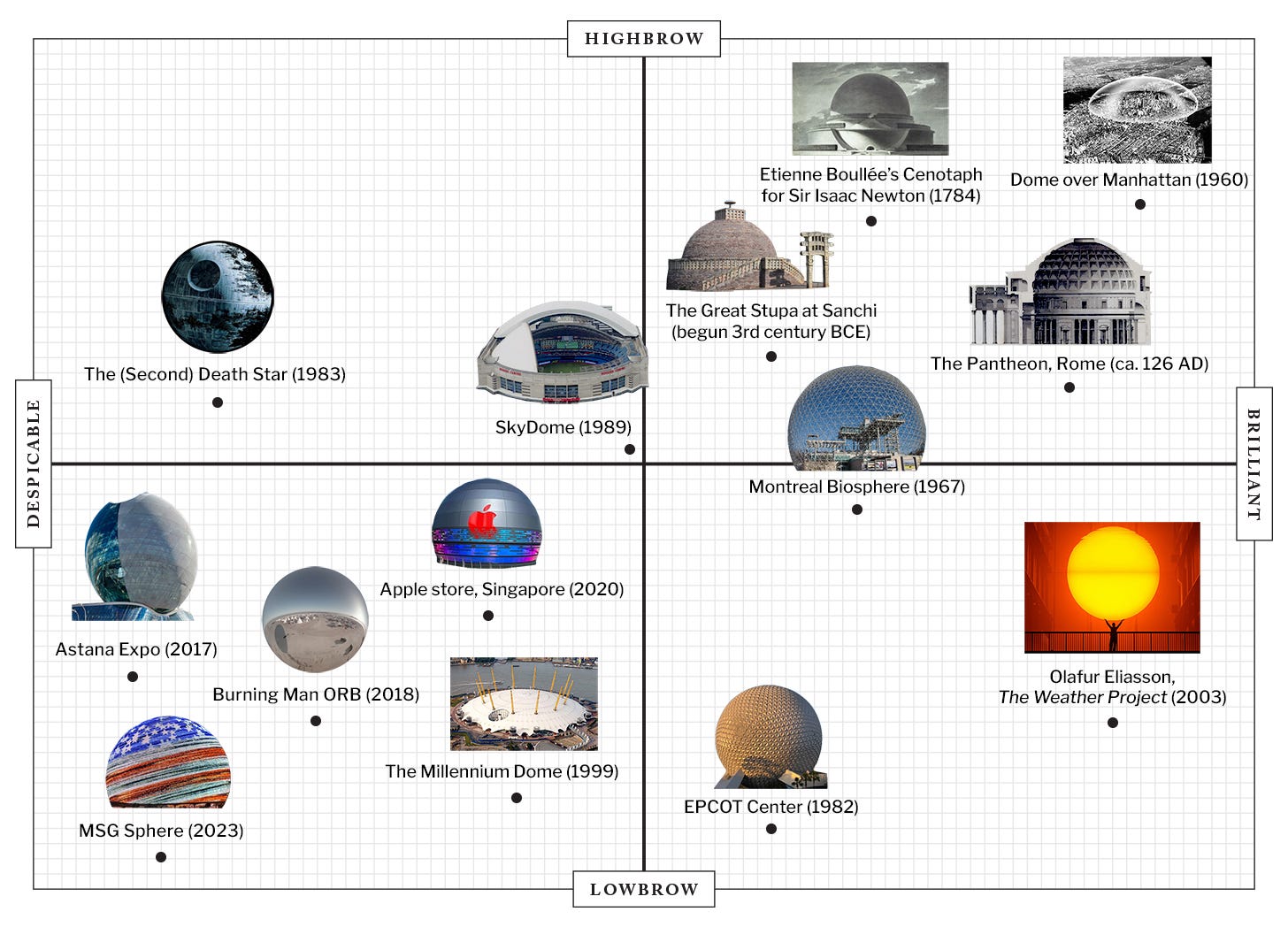

The sphere as an architectural form compels grand visions. There is Étienne-Louis Boullé’s late-eighteenth-century Cenotaph for Isaac Newton, an unrealized monument to beauty and Enlightenment thinking. Or Buckminster Fuller and Shoji Sadao’s 1960 proposal to encase a large swath of Manhattan in a glass dome to help regulate its ecosystems. Or, twenty years ago and in a more theatrical vein, Olafur Eliasson’s fantastical SAD lamp at Tate Modern.

But there seems to be little redeeming intellectual or artistic vision behind the MSG Sphere (even if you’re a fan of opening-season artists U2 and filmmaker Darren Aronofsky). The building is “a 34-story canvas for brands and event advertising” wrapped around a venue where the cheapest tickets I found online were $49 and VIP packages run into the thousands of dollars. After Summer League comes the F1 Las Vegas Grand Prix.

None of this is to deny the “dope tech” powering these experiences. It is amazing. MSG has spun off an entire content studio in Burbank, California, to create material for the building. Its teams invented a new, ultra-high-resolution camera rig to capture 16×16K footage. The Sphere has 1,800 sound cabinets capable of producing 160,000 audio channels. Ten thousand of its seats will have haptic features. There is a system to simulate scents, wind, and humidity. The numbers are mind-boggling.

But for those not ponying up, like the people who simply live, work, or play nearby, there will be “up to 18 hours a day” of brightly lit, 350-foot-tall “advertising activations, experiential campaigns, events, shows, and original art designs.” The order of that list is telling. In a recent Fast Company article, creative agency cofounder Nils Leonard brought the subtext to the surface. “[It’s] precious space,” he says. “A destination for brands that want scale and power. The win when you do outdoor right is huge. The best work doesn’t just appear on the poster, but on the phones pointing at the poster.”

The Sphere is an elaboration, using up far greater material resources, of the large, “Rain Room”–style experiential installations that have become prevalent in the art world over the last fifteen years. It’s an elaboration of the non-museum Museum of Ice Cream. It’s an elaboration of the increasingly common anamorphic digital-video billboards (splashing waves in Korea, Nikes and Louis Vuitton trunks in Tokyo, BMWs in Times Square).

The Sphere is architecture that fights against embodied experience. To borrow a famous characterization, it’s neither a duck nor a decorated shed. “The duck is the special building that is a symbol,” architects Denise Scott Brown, Steven Izenour, and Robert Venturi wrote in 1972, while the decorated shed is “the conventional shelter that applies symbols.” The Sphere’s unusual shape makes it a symbol—one that, when the lights are turned off, looks like the Death Star or the top of a microphone has crash-landed into the desert. But the ever-changing video content on its exterior means wildly varying symbols will be applied to it. (In addition to the basketball, the Sphere has already been used for a patriotic stars-and-stripes fantasia.)

It’s a building meant to be experienced through a frame: from a distance, through short-form videos on platforms like Instagram, TikTok, and Twitter; from a plane landing at Las Vegas airport; from the elevated vantage point of a nearby casino hotel; from a car windshield driving past. And it benefits from your memes. The on-the-ground experience doesn’t have the same clarity: you have to walk the blank-wall length of the Sands convention center to reach it, and even then the building is tucked behind a multistory parking garage.

“We thought, ‘Wouldn’t it be great to have VR experiences without those damn goggles?’” says Dibble, the MSG Ventures CEO. What the Sphere confirms about VR experiences, though, is that when they’re ill-considered, they’re hollow.

§

The social-media team behind the Sphere is soliciting “display ideas.” Since it exists, we might as well lobby to get some great art onto its screens and into its arena. To that end, I nominate:

- David Hartt, whose deeply researched alternate histories are both cogent and lush;

- Apichatpong Weerasethakul, whose delirious conflations of memory and history elicit deep emotional truths;

- Lawrence Abu Hamdan, whose investigative rigor could reveal so much more about how the Sphere, and Las Vegas more broadly, came to be;

- Sharon Lockhart, whose patient recordings of people and place reveal so much more than the quick-cut world we’re used to;

- Martine Syms, whose wry, self-aware video installations offer poignant meditations on identity and the creative act

And as long as we’re thinking about Sin City, let me point you to this month’s issue of The Baffler, whose theme is “Hell or Las Vegas.” As editor Matthew Shen Goodman’s introduction notes, “the city’s icons and ethos are unbounded by geography and suffuse the rest of the country, if not the world. What happens in Las Vegas, stays in Las Vegas, and Las Vegas is everywhere.”

Love all ways,

Brian

🔗 Good links—creating images in (and of) real spaces

- 🎬 How Wes Anderson created the image of a small desert town in 1950s America in the middle of Spain

- 🔲 Behind-the-scenes peek at how National Theatre teams made five theatrical sets inside one rotating glass box for Phaedra

- 🎨 Michael Sanchez’s stunningly prescient 2013 essay on how “hardware and software came together” to reshape how art is made, presented, and experienced

- 🏰 Drew Austin’s critique of the shallow “architectural traditionalism” that circulates online