Behind the Scenes: Set Pieces

On a new book Frontier designed and edited for a longtime partner

Hi everyone,

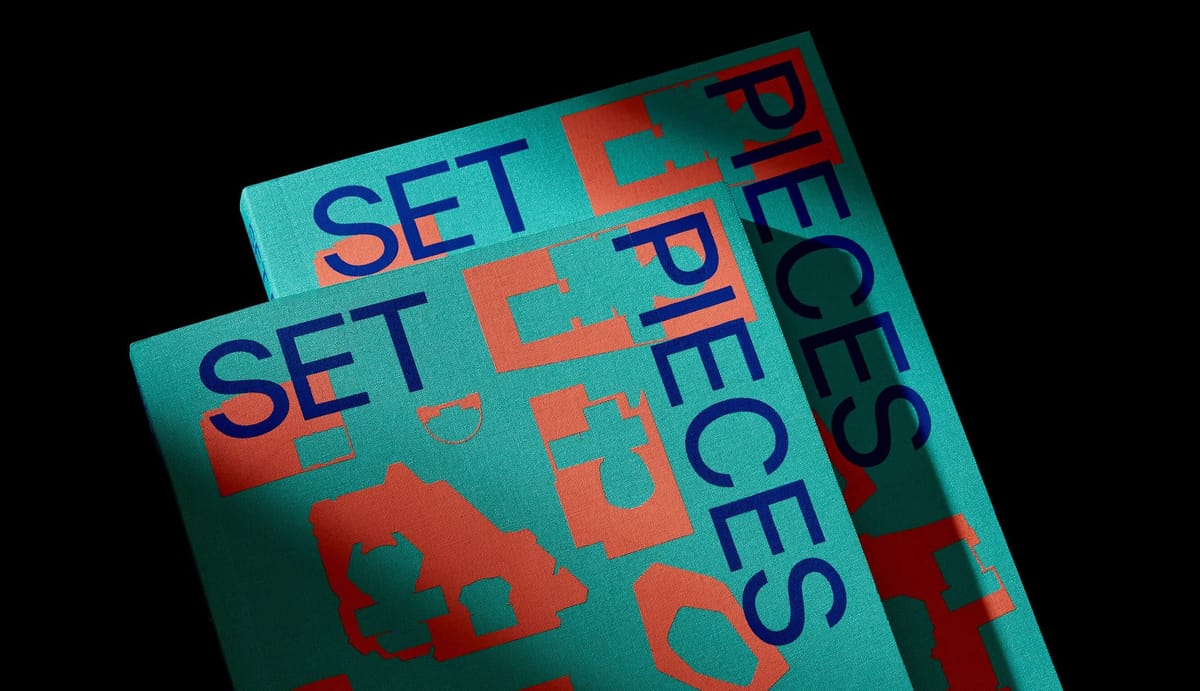

This week, a reminder that this newsletter is published by Frontier, a design office in Toronto, in the form of a behind-the-scenes glimpse at one of our recent editorial projects. Because while I write these newsletters, I am also working with Frontier’s clients on editorial and storytelling projects of all shapes and sizes. In this case, a new book, Set Pieces, which surveys Diamond Schmitt’s architecture for performing-arts halls and also asserts the value of gathering in-person for performances—even after COVID, even with infinite streaming options. Read a bit about the ideas that shaped the book below this week’s good links.

I just checked online, and a year’s subscription to Frontier Magazine is 1% of the cost of the world’s most expensive hamburger. Surely fifty-odd essays and interviews and hundreds of expertly selected links is of greater value than two hours in a Dutch restaurant. If you’ve received this email and have the means to support what we do, click to view it online and hit one of the green subscribe buttons.

Until next week,

Brian

🔗️ Good links

- 🏢👀 Buildings that caught my eye: Olsson Lyckerfors’s “wooden hybrid” 2018 student residence in Göteborg, Sweden; Edition Office’s brick-clad multigenerational courtyard house (2022); Handel Architects’ just-completed passivhaus student-residence hall here in Toronto; Tom Dowdall’s wheelchair-compatible passivhaus single-family retirement residence

- 🌳🌳 Apropos last week’s newsletter: “an unplanned green space can provide the benefits you’d get from an official park”

- ☂️🪂 My friend Diana Lind calls for an urban “shademaking movement” (I read this huddled in a sliver of shade in a neighborhood playground)

- 🚻🚾 Guido Corradi: “Public toilets are vanishing and that’s a civic catastrophe”

- 🎙️🌆 An interview with Devon Zuegel: “I see cities as expanding the palette of tools we have at our disposal to create better lives” (audio, transcript)

- 📈📉 “A century after the Harlem Renaissance, the famed Upper Manhattan neighborhood is dying a strange but predictable death”

Behind the Scenes: Set Pieces

Frontier has a long and rewarding relationship with Diamond Schmitt. The studio has updated the architecture firm’s strategic story, designed its visual identity, designed and built its website, and undertaken smaller writing efforts such as project case studies. As Diamond Schmitt made progress on a high-profile commission, its renovation of David Geffen Hall in New York, the firm’s founding partners began envisioning a way to demonstrate its decades-long commitment to designing technically adept and welcoming spaces for the performing arts. “Having worked with Frontier previously, we knew immediately they were the team to entrust with communicating the essence of our firm’s work for performing-arts halls,” says Donald Schmitt.

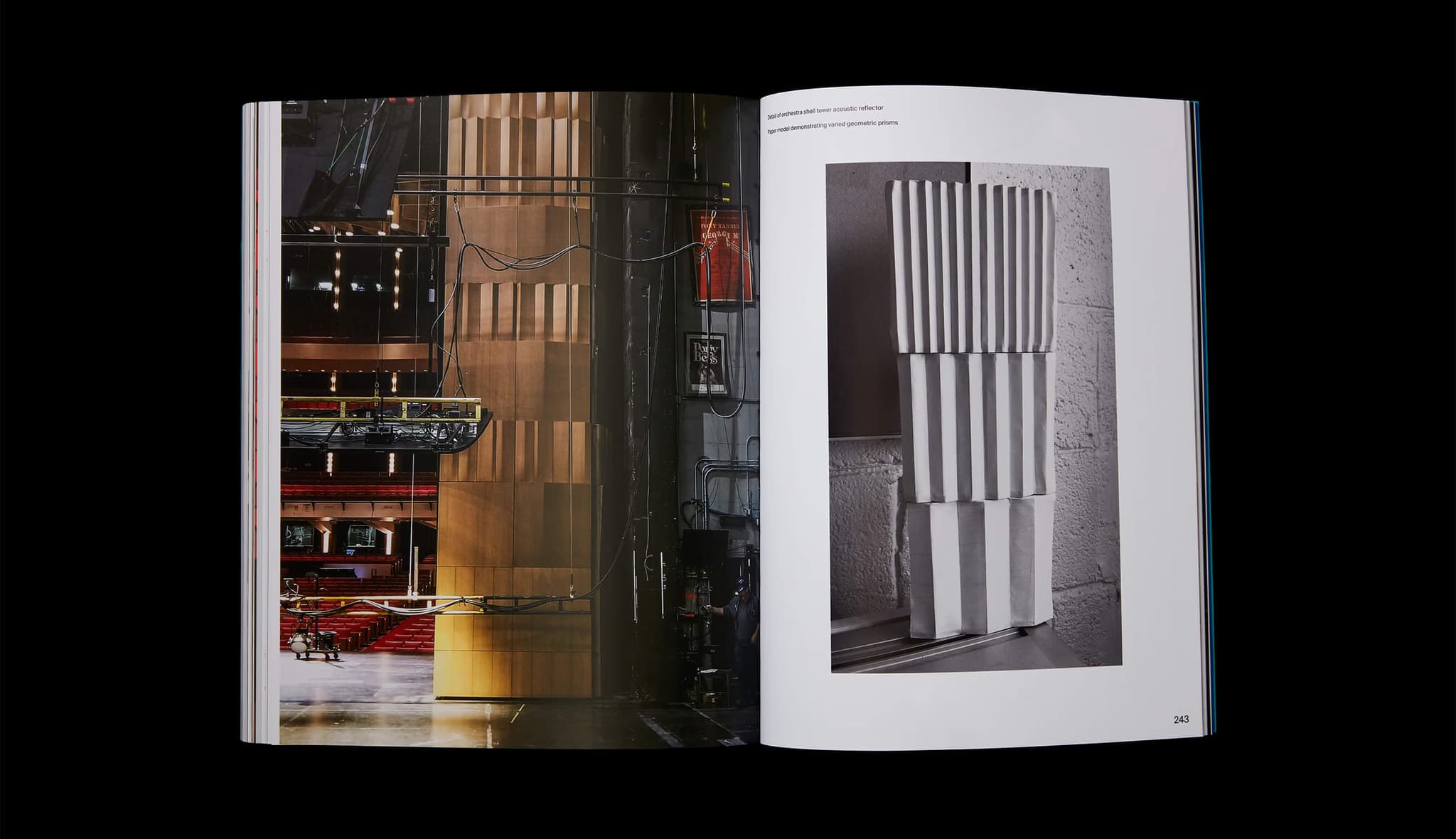

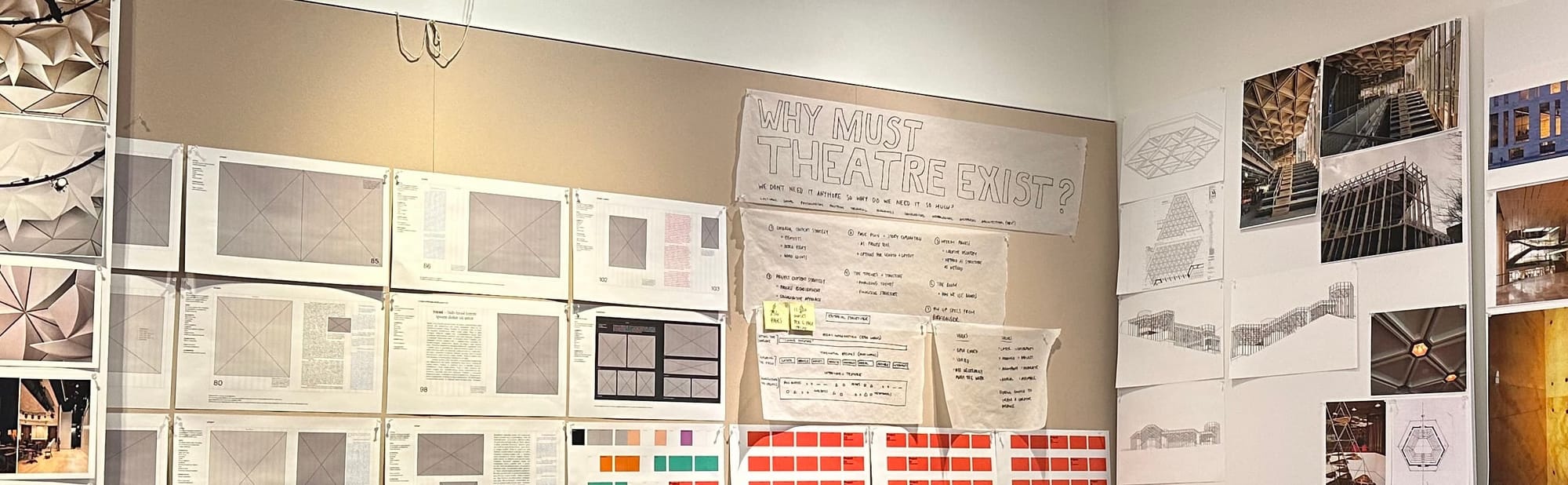

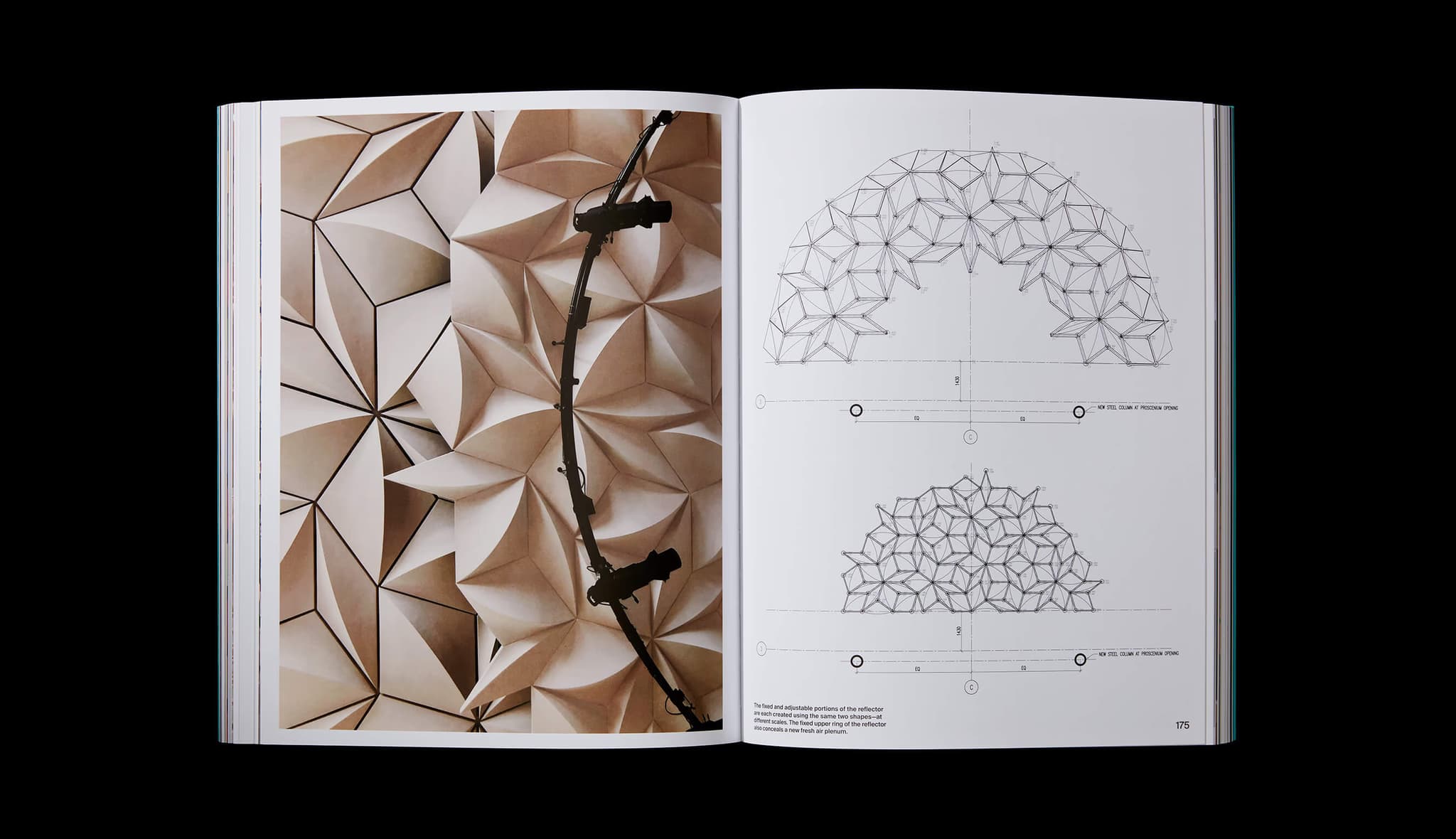

In turn, Frontier founder Paddy Harrington brought in editor Jennifer Sigler, whose career has included stints at prestigious institutions in the United States and Europe. Together they settled on an unusual structure and ambition for the book. First, rather than conventional case studies, the story of Diamond Schmitt’s projects would be told through design “fragments”: the design of a lobby staircase, say, or the acoustic reflectors that send sound throughout a room. Second, the book’s texts shouldn’t limit themselves to the firm’s work, but rather speak to the deeply affirming experience of gathering in-person to experience art. A handwritten note affixed to the top of the pin-up boards we used for layout kept our focus constant, asking, “Why must theater exist”?

I had joined the project around this time, and worked with Paddy, Jennifer, and several people at Diamond Schmitt to draft long lists of potential contributors. We knew we wanted the voices of both critics and artists. We eventually settled on critical contributions by two very different writers. The lead essay is by Justin Davidson, who studied music composition and has been both architecture and classical-music critic at New York magazine for more than fifteen years. A second piece is by Kate Wagner, known for her satirical blog McMansion Hell and for engaged writing on the politics of architecture, whose graduate studies in architectural acoustics included deep research into Avery Fisher Hall—the very building Diamond Schmitt was renovating.

But how would we select from the countless wonderful artists we admired, or even the still-large number that had performed in a Diamond Schmitt building? The list was long, but we eventually settled on three: Robert Lepage, Mimi Lien, and Robert Gerard Pietrusko. Lepage is not only a celebrated theater director and filmmaker who had staged stirring and experimental work in the firm’s Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts, but also an architectural patron who had built Le Diamant, a multipurpose arts venue in Quebec City. Lien is a Tony Award–winning set designer who is working with increasing frequency in public spaces, as with her 2022 installation for The Bentway in Toronto. And Pietrusko is a scholar, design practitioner, and musician who has created sound installations that are constituted by their architectural surroundings.

Our critics wrote about “stepping across the gap between routine and revelation” and about “how to listen, which often means forgetting how to look.” Our artists spoke about how a good theater design can “decontaminate” an audience—how it can separate people from their everyday concerns—and can “support the sense of reality” in a show.

What remained was the opening and closing of the book. We collectively decided not to trumpet Diamond Schmitt’s achievements but rather to address the animating impulse behind the buildings showcased within its pages. (And, for that matter, the many competition designs that were not selected, two of which appear in the book.) Donald Schmitt hearkened back to a 1983 competition entry for London’s Covent Garden that convinced the firm that “architecture can intensify the connection between the arts and surrounding communities.” Matthew Lella emphasized that the best performances are multisensory, and the kinds of spaces in which they occur co-evolved over centuries with the art forms they house. And Gary McCluskie uses the words of the beloved Toronto conductor Richard Bradshaw to meditate on how “great spaces for performance encourage artists and audiences alike to give their all,” to be reciprocally vulnerable.

In some sense, all creative projects, undertaken in good faith, encourage that reciprocity. You know you’ll be transformed by the effort and, for my part, I can say the collaboration changed me for the good. So let me thank our closest partners and express the hope that they feel similarly. I’m grateful for the trust Diamond Schmitt placed in us, and for the heroic efforts by Jennifer; Javier Zeller, who was also designing buildings for the firm while tirelessly managing this project; and Cristian Ordóñez, the book’s designer.

To see many more spreads from the book, check out Frontier’s case study for the project. To buy it, visit the book’s page on the Birkhauser website. And, of course, if you’ve got a story you need help telling, just hit reply and tell us a bit about it. We’re here to help.