Big Digs

Radically different visions of sustainable architecture, in Boston and rural China

I moved to Boston for university during construction of the “Big Dig,” a decades-long infrastructure project that involved creating two expressway tunnels, a bridge over the Charles River, and new public green spaces downtown. For all its flaws (its $22 billion price tag won’t be paid for until 2038!), it radically reshaped the city—ultimately for the better. Its nickname is etched in my mind.

A conversation last week with architect Paulo Rocha, of KPMB, dredged that phrase from memory. He was talking about the thirty one holes, each deeper than the Empire State Building is tall, that were dug to create the geothermal energy powering the newly opened Center for Computing & Data Sciences at my alma mater, Boston University. A very big and creative dig, if not quite a Big Dig.

The phrase rattled around until I connected it with a very different project: architect Xu Tiantian’s adaptive reuse of abandoned quarries in rural China. Where the BU tower took about a decade and $300 million USD, her team began designing in June 2021 and work on three projects was done by early 2022. Here, the digs had taken place over centuries, and her task was to rehabilitate the gashes they created.

Both efforts have unexpected elements that bring joy to their visitors, whether it’s a torquing tower or the sheer surprise of rural outdoor cultural spaces. And both offer scintillating, if different, visions of environmentally sensitive building practices. Read on to learn more—and hit reply to send me your own favorite recent sustainable buildings.

–Brian Sholis

This interview, conducted on January 18, 2023, has been lightly condensed and edited.

Brian Sholis: Large-scale university projects often bring together departments or disciplines that had previously been housed in separate buildings. Was that the case here and, if so, can you talk about the programmatic opportunities that encouraged?

Paulo Rocha: It was the case here. It was initially three departments—math, statistics, and computer science—but as the building evolved the university formed a new faculty called Computing & Data Sciences. The programs brought together obviously have synergy—they’re all involved in the study of data. Because of this synergy, the building needed to maximize interaction between them as a way of fostering a broader sense of community.

So we emphasized openness to encourage collaboration and movement, which enhances the experience for both faculty and students. Because of its constrained site, it becomes a vertical campus. To break down the building’s scale and to give a distinct identity to each department, we created two- to three-story “neighborhoods.” They do more than just promote community and identity, the shifting volumes also give us opportunities for outdoor spaces.

BS: The overall shape of the building seems to have been in place since the competition phase. Can you talk about what led you to the stacked and torqued volumes?

PR: We wanted to change the idea of what a tower can be. The form speaks more to what’s happening inside the building rather than giving the same space and configuration to every floor. The immediate context also prompted the decision to break down the tower’s scale into neighborhoods. The nearby brownstones are three and four stories; this building’s podium is five stories, which aligns with the university’s Arts & Sciences building to the west and the Sargent College building to the east.

The brief called for something remarkable and iconic; we knew a standard tower wouldn’t cut it. So even our competition entry contained the idea of movement and circulation through a vertical campus.

BS: You mention the surrounding context but neglected to say something about the three-tower residence hall across the street …

PR: The “three sisters” building primarily offers solid walls, even at street level. So our building is almost a rejoinder to it, and by extension to the campus designs of the 1960s and ’70s. That building is closed off. Ours prioritizes connectivity, openness, drawing people in from the street. It’s glazed, porous, vibrant. The busyness and activity of Commonwealth Avenue can spill into the core. These characteristic are part of the DNA of our practice: collaboration, openness, giving back to the public realm.

BS: Only about two percent of all US universities get some of their energy from geothermal sources. Can you discuss choosing a closed-loop geothermal system as your sustainable-energy source?

PR: For context, we won the competition in 2013. Back then, developers were basically looking for LEED certification. But we always knew the process would be put on hold—that had been communicated early on. And before we picked it back up in 2018, Boston University put together a climate-action plan that involved getting to carbon neutral by 2040 (ten years ahead of the City of Boston’s goal).

So we knew the building had to be carbon neutral and fossil-fuel free. How could we achieve that? Solar panels across the whole building? Solar technology wasn’t yet able to produce enough energy. Geothermal was the best choice. So we dug thirty-one boreholes into the ground, down to 1,500 feet, and added a energy-efficient triple-glazed façade.

As part of its plan, BU committed to buying nonpolluting wind power from a wind farm in South Dakota to offset its carbon emissions in Boston. That’s part of the university’s answer to how you decarbonize existing buildings. You can’t renovate every existing building, but you can be smarter when building new. This tower is the exemplar for how the university moves forward in design.

BS: Part of what makes its massive geothermal project work is that BU owns land around the building and could place bore holes “off-site,” so to speak.

PR: Yes, that helped. That’s not to say that developers can’t do sufficient geothermal power on-site. Putting bore holes off-site also meant we could construct the tower and do the digging at the same time.

BS: And for developers without access to extra land and can’t take advantage the way you could, what incentivizes geothermal?

PR: The City of Boston is evolving its building-emissions reductions measures. There will be penalties for buildings that don’t hit the targets. That’s one way to incentivize sustainable approaches like geothermal energy. To really move the needle today, you need people with foresight and vision, as we had with our university partners.

For many developers, though, money talks. Today, governmental policy is the primary way to make sure the average developer takes sustainability seriously. In addition to that, people increasingly want to live and work in sustainable buildings. We are all aware of environmental challenges, and if you’re a company’s real-estate lead taking a lease on 300,000 square feet in a tower you want that building to lead by example. The largest companies out there are trying to be better citizens, they’re looking for better options.

BS: Now that the building is complete and students and faculty are beginning to use it, can you speak about a favorite part, or something that surprises you about it?

PR: We were confident we’d made a good building. I think what people have found surprising is how much they love the interiors. What the building does for Boston’s skyline at the macro scale, the interiors do at a micro scale. The collaboration spaces, the warmth, the sense of movement all lead to nuanced and rewarding uses. The energy the building spins off toward the city is mirrored at human scale inside it.

Deep Cuts

In spring 2021, officials in rural Jinyun County, China, invited Beijing-based architect Xu Tiantian to propose ideas for converting some of the region’s thousands of abandoned quarries. At the turn of the century, mining had been halted due to ecological concerns, and county officials sought ways to honor the legacy of hard labor while revitalizing these unusual and inactive spaces.

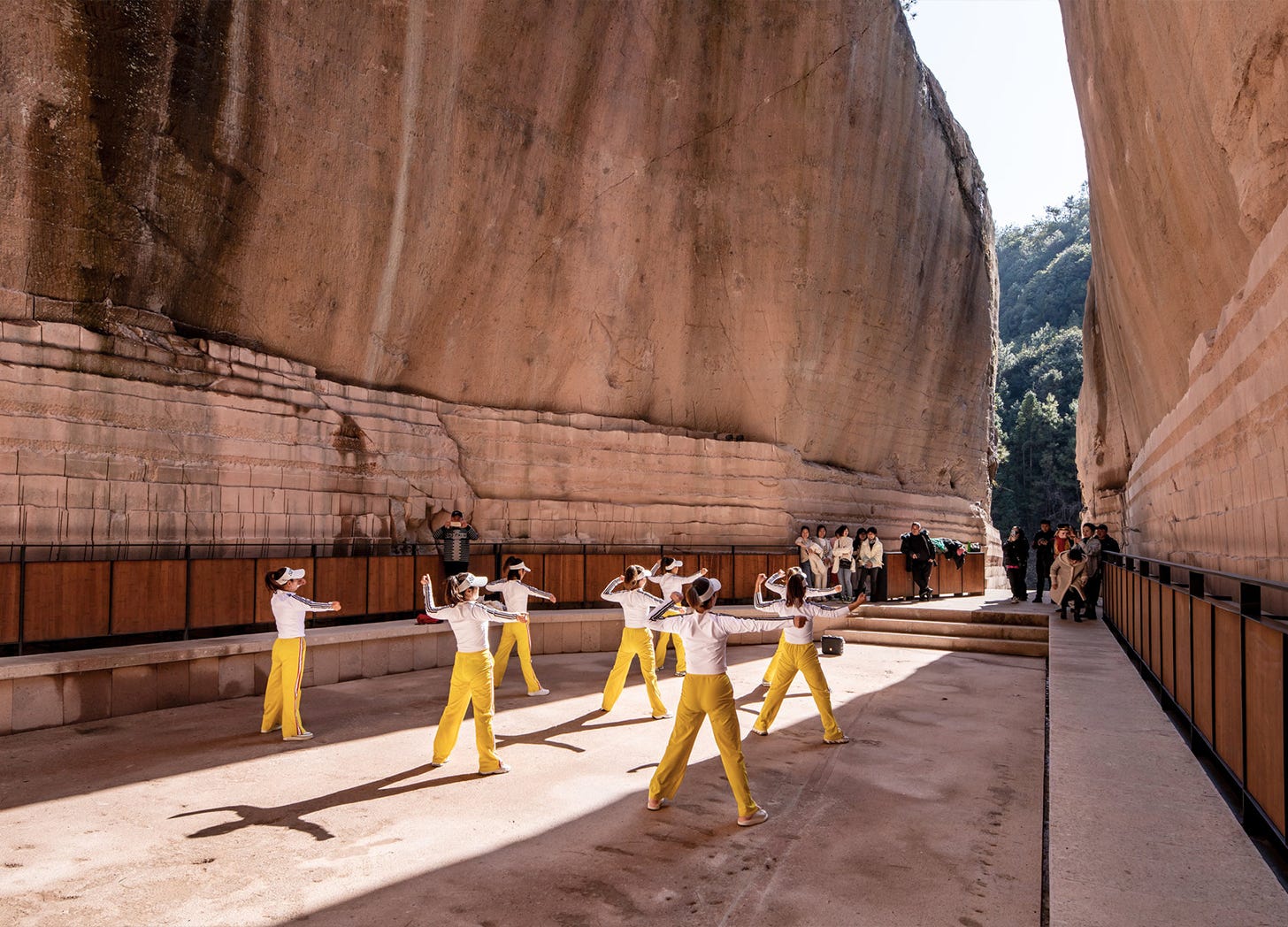

Xu’s firm, DnA_Design and Architecture, ultimately chose to create a series of engaging public spaces within nine quarries along a one-kilometer footpath. Work began quickly on three: a space for demonstrating ancient stonemasonry techniques; a library and study center poetically named Book Mountain; and an open-air performance venue. Others will create a restaurant, a tea house, and an information center to share stories for tourists and locals alike.

Xu’s interventions tread lightly, rehabilitating disused and spoiled places with little additional material. Yet the experiences they create offer dramatic contrasts between the craggy and the organic and her sober designs. She has crafted places that are at once landscape, interior, and land art.

But to see them for their formal qualities alone is to miss how they benefit the local community. As she said in a recent interview, “It’s not about superimposing. Behind these strategies is the community, the people, a collective that makes up the culture.” She continued: “With minimal design intervention, these spaces could be transformed into something significant, with a new public program for villagers who have a strong emotional connection to these places. It’s not about the signature of the architects, but about design being a supporting element to make these spectacular, monumental spaces accessible.”

With thanks to Eduard Kögel, whose study of Xu Tiantian’s work has led to articles and an exhibition in Berlin.

Good Links

- 💨 “Like my mother used to tell me, you let the wind come through.” In this TED talk, Designer Alyssa-Amor Gibbons on climate-resilient architecture that learns from local traditions.

- 🏡 “In a city that aggressively markets itself as the most culturally diverse in the world, suburban communities like Scarborough, often overlooked, epitomize that aspiration.”

- 🚶🏻♀️“Walkability should be used as a catalyst for developing sustainable, healthy, prosperous and attractive cities”: a report from Arup.

- 📚 If you’re visiting Boston soon, try travel writer Paul Theroux’s literary tour of the city.