Building Capacity

Lessons on humility and climate resilience from two Mexican architecture firms

Hi everyone,

During the 2000s and 2010s, colleagues in the contemporary-art scene began watching—and regularly visiting—Mexico City. Great galleries, like kurimanzutto, introduced us to a generation of innovative Mexican artists, and museums, among them collector Eugenio López Alonso’s Museo Jumex, contextualized that work with exhibitions by international stars. Through that focus, I became increasingly interested in the city’s architecture scene, admiring buildings like the Elena Garro Cultural Center (2013) by Fernanda Canales and arquitectura 911sc and learning about forward-thinking firms, often led by women, offering creative solutions to some of the country’s most pressing problems.

Below, I briefly discuss two of my favorite architecture firms in the city, Comunal and Taller Capital, which have both built unique and impactful projects rooted in public consultation. Designers often pride themselves on their ability to consult with and discern the needs and desires of their users. By actively and deeply engaging the communities for whom their projects are being built, Comunal and Taller Capital build capacity: of the local populations’ skillset and knowledge, of an ecosystem’s resilience. They offer a model of architecture worth considering—and celebrating, as indeed awards bodies in the United States and elsewhere have begun doing.

For more on architecture, dive into the Frontier Magazine archives for a January piece on sustainable projects in Boston and China; a summer 2022 conversation with Group AU on using architecture to make a small city in the Berkshires more equitable; or this review of a recent book profiling six generations of women architects.

Love all ways,

Brian

Comunal

Mariana Ordóñez Grajales and Jesica Amescua Carrera founded Comunal in Mexico City in 2015. As the name suggests, they believe architecture should be collectively authored and evolve dynamically with a community’s needs. Working under a framework they label the “social production and management of habitat,” this interdisciplinary group of women designers collaborates with rural populations, often Indigenous, to co-create buildings that reflect community knowledge.

Their commitment to participatory design sometimes takes even peers by surprise. “We try to create a dynamic where the community can draw all the things they want … [and] can express the symbols behind their traditional architecture,” Amescua Carrera said in one dialogue. “The drawings are made more by the community than by us. We’re the interpreters.” “I’m not sure I believe that,” came the response from a fellow architect who was impressed by Comunal projects’ formal rigor. Ordóñez Grajales proceeded to explain how even the shapes of the window screens in one housing project draw on pre-Hispanic cultures and can identify the village where the house is located, information gleaned from Tepetzintan residents during workshops.

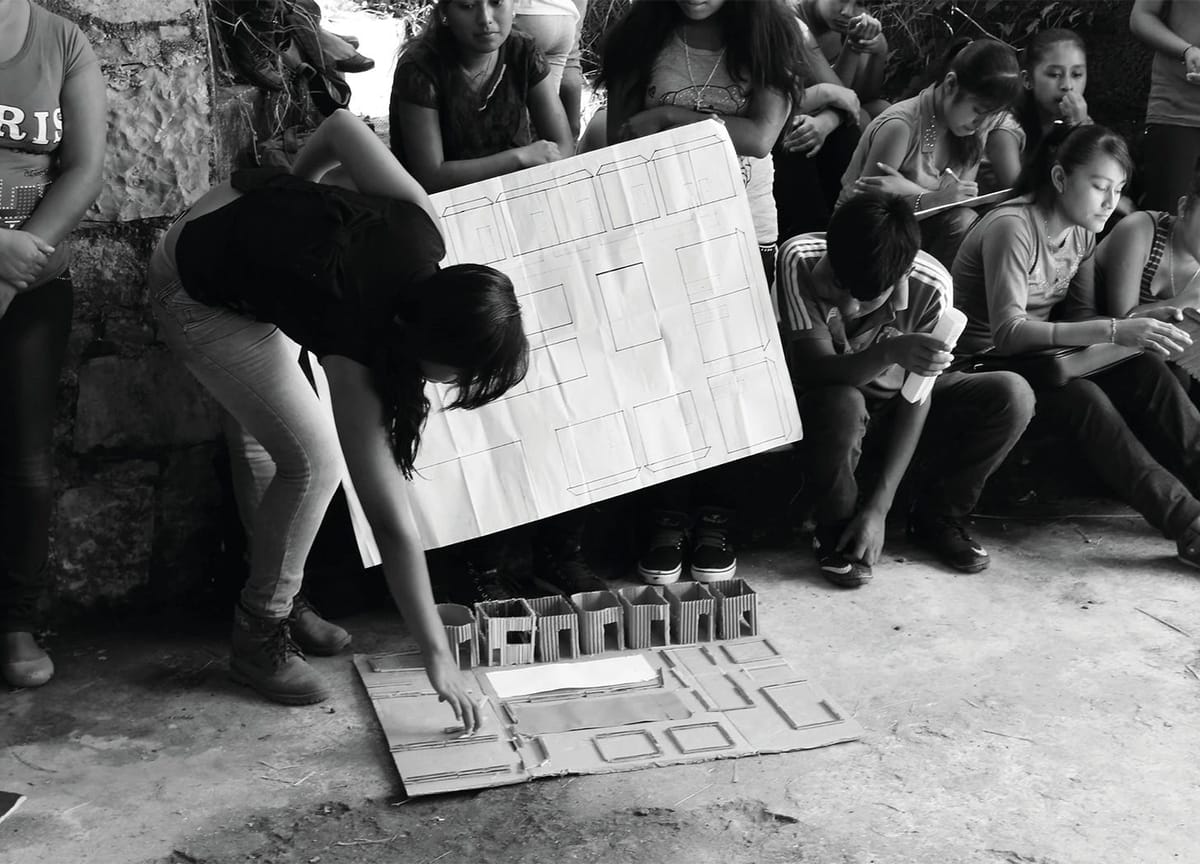

A more recent project in the same community, which is about three hundred kilometers northeast of Mexico City, involved designing educational spaces with the high-school students that would both build and use them. The students presented the project to the community and received a land donation in return. Parents created a committee to organize the work and contributed construction materials. The first phase of the project opened in 2018 and the buildings are in now use both for regular school activity and workshops, some on traditional construction methods, open to everyone in the vicinity.

In addition to their built work, Comunal have been articulate and forceful critics of the biases, both cultural and legal, that downplay traditional knowledge and limit how architects can engage with less privileged populations. For example, Ordóñez Grajales and Amescua Carerra visited Oaxaca after the devastating 2017 earthquake and penned an open letter criticizing president Enrique Peña Nieto for his statements on how best to recover and rebuild from the disaster. And their advocacy is not only rhetorical. When the authorities refused to allow Comunal to replicate the Tepetzintan social-housing prototype because it uses bamboo structurally, and therefore was deemed “unsafe,” the designers helped to create a second building. This one was created in consultation not only with locals but also the National Housing Commission. The resulting structure can be built quickly and cheaply by local communities; has helped shape the dialogue on housing policy; and even won a silver medal from the Commission.

“[Our work] is based on the belief, apparently radical for many, that the inhabitants of any social group and cultural context have the capacity to identify their needs, propose solutions and make the appropriate decisions for the development of their territory,” Ordóñez Grajales and Amescua Carerra said in a 2020 interview. “If you had told us a few years ago that we were going to be able to work collaboratively with Indigenous peoples and do what we are most passionate about, we would not have believed it.”

Taller Capital

If Comunal stretches the conventional definition of architecture to make it more participatory, Taller Capital expands it in another direction, bringing it closer to infrastructure. For its interventions into public space, Taller Capital, founded in 2010 by José Pablo Ambrosi and Loreta Castro Reguera, often engages communities in more densely populated locations: the outskirts of Tijuana, say, or just west of Nogales, a town on the US-Mexico border. Such community involvement often enables the firm to weave peoples’ needs into projects meant primarily to address deteriorating systems—which, because of Reguera’s deep study of the issue, means water management. The impacts of climate change make water a social issue of increasing importance; her philosophy of “hydro-urban acupuncture” calls for bottom-up solutions that address both infrastructure and culture.

Several years ago, the firm responded to a brief for a project on the informally urbanized southwestern edge of Tijuana. The call was for the construction of sidewalks and a water-runoff system to help clean a polluted ravine. But after consulting with the people whose homes pack the surrounding hillsides, Taller Capital discovered an urgent need for usable public space. So, in addition to channeling the water in helpful ways, Ambrosi, Reguera, and their team covered the ravine with Parque Xicoténcatl, which includes playground equipment, basketball courts, recreational space, and low green slopes held in place by llantimuro, a vernacular building technique that repurposes rubber tires. In doing so, they solved both environmental and social problems, stitching together neighborhoods that previously only looked across to each other over a dirty waterway.

In 2020, the firm completed a project in Nogales, on the US-Mexico border, that undid the ill effects of a 1960s–era dam that had been overrun for decades. Initially asked to design a park next to the water, the firm instead transformed the dam itself: by installing gabions, or wire containers filled with stone that hold earth in place while allowing water to pass, for example, and by surrounding it with rings of flood-resilient platforms. Add in recreational spaces and an iconic triangular pavilion that references the surrounding vernacular architecture, and you have a welcoming space where once there were regular sewage-strewn floods.

Taller Capital is also known for its public buildings and its elegantly austere private residences, but these infrastructure efforts are what align them, in my mind, with Comunal. In a statement that wouldn’t sound out of place coming from Ordóñez Grajales or Amescua Carrera, Reguera has said, “I believe the future of Mexican architecture lies in looking at the other 80 percent.”

One More Thing

“In Mexico City, everywhere is a place where water used to be.” Reading about Taller Capital’s focus on hydrology called to mind a wonderful 2020 essay by the Cape Town–based writer Rosa Lyster, who is at work on a book about the global water crisis.

“I’d always thought people were being metaphorical when they said that Mexico City was sinking, or at least that the evidence of it would be invisible to anyone other than a hydrologist or an engineer. But no: the city is subsiding as it draws more and more water from further and further below the surface, collapsing into the clay lake-beds on which it was built, and even someone who doesn’t know what an aquifer is can see it.”

Featuring grandmothers that hold water-truck drivers hostage at gunpoint and an ability to connect what she sees to “water stresses” in South Africa, India, and Zimbabwe, Lyster comes to a somber conclusion: “The problem is not water scarcity, although it now presents itself as that. It’s a problem of water management, and infrastructure, and inequality.”

Good Links

- 🏆 The finalists for the 2023 Mies Crown Hall Americas Prize were announced two weeks ago

- 🔨 “We believe in the hammer of struggle and in the power of hope. Hope is a discipline, not unfounded faith. It is the deeply held belief that a better world is possible if we fight for it.” From the introduction to Hammer & Hope, a new magazine of Black politics and culture.

- 👟 Nike’s chief design officer on the future: “I’ve also had a chance to see where it’s going. What happens is, designers become more about curating and adjusting parameters, and still editing and beautifying. I’m incredibly excited.”

- 🛋️ “I didn’t slip my stocking feet under Dave’s legs, because I’m not a weirdo, but I would have liked to.” On the power of just hanging out.