Design to Protect Democracy

Fighting disinformation with design and data.

Yesterday was election day in Canada, and with a 25% increase over 2021 in early voting and a record turnout, there was clearly an abundance of enthusiasm for this year’s big decision.

Americans will recognize this anticipation. The 2024 presidential election saw the second largest voter turnout in history. As with Liberals and Conservatives in Canada, there was a lot of excitement and a high degree of confidence, for both Republicans and Democrats, that their side would win.

But other forces were at play. According to a study by Pew Research, both Democrats and Republicans felt a strong surge of made-up news, especially online, in the lead up to the 2020 election. It’s become more prevalent in the half-decade since.

We can no longer trust our information. If there’s truth in the adage that you should believe half of what you see and none of what you hear, then you should believe even less of what you read on Facebook. These issues will only become worse with the surge of AI-generated news. As a result, most citizens are left to fend for themselves, increasingly isolated and divided from friends, families, and communities as they swim in a sea of algorithm-driven confirmation bias.

With no shared truth, it’s impossible to cohere as a society.

The rise of disinformation means that battles are being fought in Canada, America, and many other nations. And despite no soldiers stepping foot on foreign soil, these battles profoundly affect the direction of nation states. This invisible war is of indeterminate scale and duration. Fuelled by business models that reward hysterical headlines with dollars, it’s hard to conceive of a path toward reestablishing a shared truth, or story, that we can trust, even if it's not the story that we're hoping for.

The future is about designing for and fighting back with data. In the Philippines, Nobel Peace Prize–winning journalist and activist Maria Ressa, through her news outlet, Rappler, has spent years fighting the Duterte regime’s disinformation. Now she’s shared the lessons she learned in a roadmap for the future called How to Stand Up to a Dictator (buy in the US or Canada). For those with a little less time, this talk on the roots and anatomy of disinformation is an hour worth spending; as is this podcast interview with Jon Stewart.

Ressa’s careful analysis of social-media platforms leads her to argue that disinformation networks are so deeply coordinated and targeted that they can affect opinion on any public figure and across any segment of society. Why does this matter? She outlines three key factors:

- Democracy Depends On Truth: Ressa argues that democracy cannot survive without facts, and the erosion of shared facts—due in large part to misinformation and disinformation on social-media platforms—undermines democratic decision-making.

- The Role of Technology Platforms: She criticizes platforms like Facebook and YouTube for the algorithmic amplification of lies over facts, which splinters the public sphere into separate realities. This weakens the shared informational space and erodes trust.

- Information Ecosystem Crisis: She links the breakdown of this trust to a larger crisis in the information ecosystem, where the lack of shared understanding leads to polarization, populism, and authoritarianism.

She notes that on social media, 83 percent of people say they distrust traditional media. The implications run deep. As she says: “Without facts, you can’t have truth. Without truth, you can’t have trust. Without trust, you have no shared reality. And it becomes impossible to have democracy.”

So what do you do? For Ressa, you dump the data into a database, then identify fake accounts that distribute fake information. By doing so, you create a map of influence. For example, her team calculated that even just twenty-six accounts affected three million people across a range of social and economic groupings.

Ressa identifies three imperatives. To solve this crisis, we must:

- Regulate tech platforms to prioritize factual integrity over engagement. And invest in public broadcasting to create accountability.

- Invest in independent journalism that verifies and upholds the truth.

- Create new norms and structures that protect the information commons, such as international frameworks for truth in media and tech accountability.

How can design help? Here are two critical ways design can help us work our way back to a united reality.

Visualize the Issue

As Bruce Mau would say, by making the invisible visible we can better understand abstract ideas, which puts us in a better position to respond to the issues they visualize.

A young Stewart Brand asked Buckminster Fuller to advocate for a photo of earth from space. The idea, in Brand’s mind, was that if we could have more people see an image of the earth as a sort of spaceship surrounded by the void of outer space, we might better appreciate the importance of protecting it.

Similarly, we must create images of these “alternative spaces where reality is slightly different.” We need to return to truth, to earth.

Ressa does this. Her visualizations make the invisible visible. Design can augment this effort so that the issue is more tangible and, as a result, something we can act on together. In a 2016 article on the subject of weaponizing the internet, she describes one online conversation focused on shifting the opinion of online targeted groups.

The first groups to actively use the power of social media, including its dark side tactics, were corporations and their allies. They used a strategy popularized in the computer industry in the US known as FUD—which stands for Fear, Uncertainty, and Doubt—a disinformation strategy that spreads negative or false information to fuel fear.

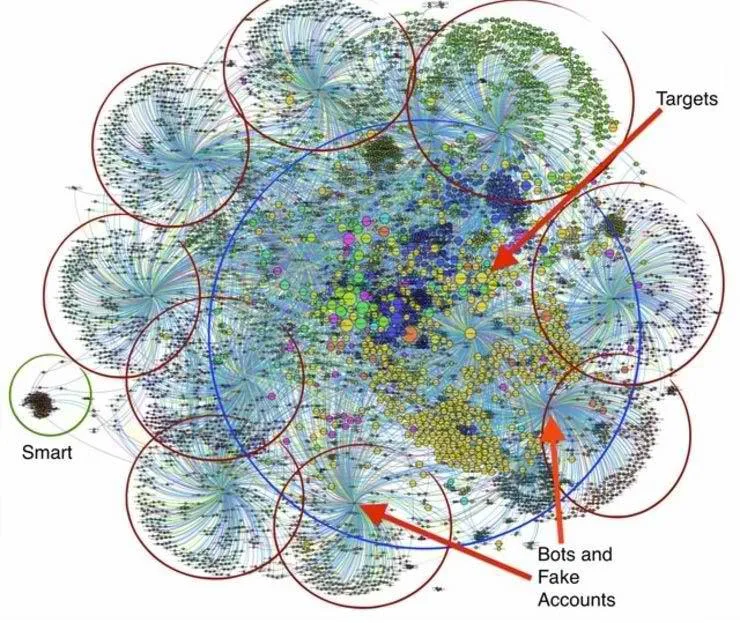

In a nutshell, if you use the hashtag, it signals a bot to message your account—to sow fear and doubt to trigger anger—a classic FUD campaign. That’s coupled with fake accounts which continue the campaign. (The greenish-blue line are bots, which attacked at such a high frequency that it effectively shut down the green Smart campaign.)

Here’s a map of the conversation, laying bare a familiar communist strategy: “surround the city from the countryside”—effectively shutting out the Smart Twitter account from its targeted millennials.

Maria Ressa, Rappler.com

Rappler’s visualizations have shown how fake accounts, pages, and groups are coordinated to push certain political narratives. These network maps make abstract ideas (like “coordinated inauthentic behavior”) visible and understandable.

The first step in understanding something is measuring it. In our increasingly visual culture, visualization is, in effect, an act of naming. Design is a means to translate complexity into easier-to-comprehend information and should offer itself in that service in this continued quest toward an ever slippery and many-faceted “truth.”

Design that Makes Truth Sticky

It’s important that we create a shared truth but as important that we entice and encourage people to engage with it. Ressa calls for a shared public-information trust built on the foundation of reliable, verified facts that a society can rely on to make decisions, hold power to account, and engage in democratic discourse. This trust is crucial for civic life, public policy, and even the functioning of democratic institutions. Social-media companies have deployed billions of dollars to design user experiences that hook us by using our neurological hard-wiring against us. Without a similar effort to support sources of truth, there is no chance those caught in the web of social-media platforms, where disinformation has become the baseline, will ever escape.

Bad News is a platform designed to help youth navigate the world of online disinformation. The player takes on the role of a fake content creator and helps them learn “pre-bunking” strategies designed to help identify and pre-empt disinformation online. Since its launch, the Bad News game has been translated into over fifteen languages and has reached more than a million players worldwide.

Lead Stories is an independent fact-checking website established in 2015 and dedicated to identifying and debunking false, misleading, or satirical content circulating online. Its proprietary Trendolizer™ technology helps users monitor trending topics across social-media platforms to promptly fact-check viral claims. While it does not focus on UI, it has partnered with Facebook to help users on that platform quickly check if the information they were seeing was real or fake. Sadly, in early 2025, Meta announced the end of its third-party fact-checking partnerships in the US, impacting collaborators like Lead Stories.

Finally, MediaWise is a nonpartisan, nonprofit digital-media-literacy initiative led by The Poynter Institute. Launched in 2018 with support from the Google News Initiative, MediaWise aims to teach people of all ages how to discern fact from fiction online. Since its inception, MediaWise has reached over twenty-onoe million individuals through educational content and fact-checking training, with its materials viewed more than sixty-six million times. Among the tactics used by MediaWise are short-form videos tailored to platforms like TikTok and Instagram Reels—where the scroll behavior, autoplay, and algorithmic feeds inherently promote stickiness. They also deploy teens as creators. The Teen Fact-Checking Network (TFCN) involves youth in producing the content, which helps the material resonate with its audience and encourages peer-to-peer sharing.

What it all Means

Through her work with Rappler, Ressa has exposed state-sponsored disinformation networks in the Philippines and drawn clear connections between Facebook’s algorithms and the rise of populist, authoritarian governments.

Her investigations have influenced discussions on tech regulation globally, including initiatives in the EU (like the Digital Services Act) and policy debates in the US about regulating social-media companies.

Ressa has faced numerous arrests and legal cases in her efforts to fight online disinformation, many of which are seen as politically motivated. She describes her own journey in the Philippines as the “canary in the coal mine” for what we are experiencing around the world. Despite her efforts, authoritarian tactics—including digital harassment, legal threats, and troll armies—continue to be effective.

While there have been improvements, major platforms like Facebook and YouTube have been slow to meaningfully reform the business models that prioritize engagement over truth. The battle against disinformation is far from over.

The problem is systemic, and won’t be solved without systemic platform changes. But design can play a role in the first part of the quest: to help more people see and understand what is fact, and what is not.

🇵🇭 Rappler.com (Subscription required)

🦝 Dark Pattern Design