Eastern Promises

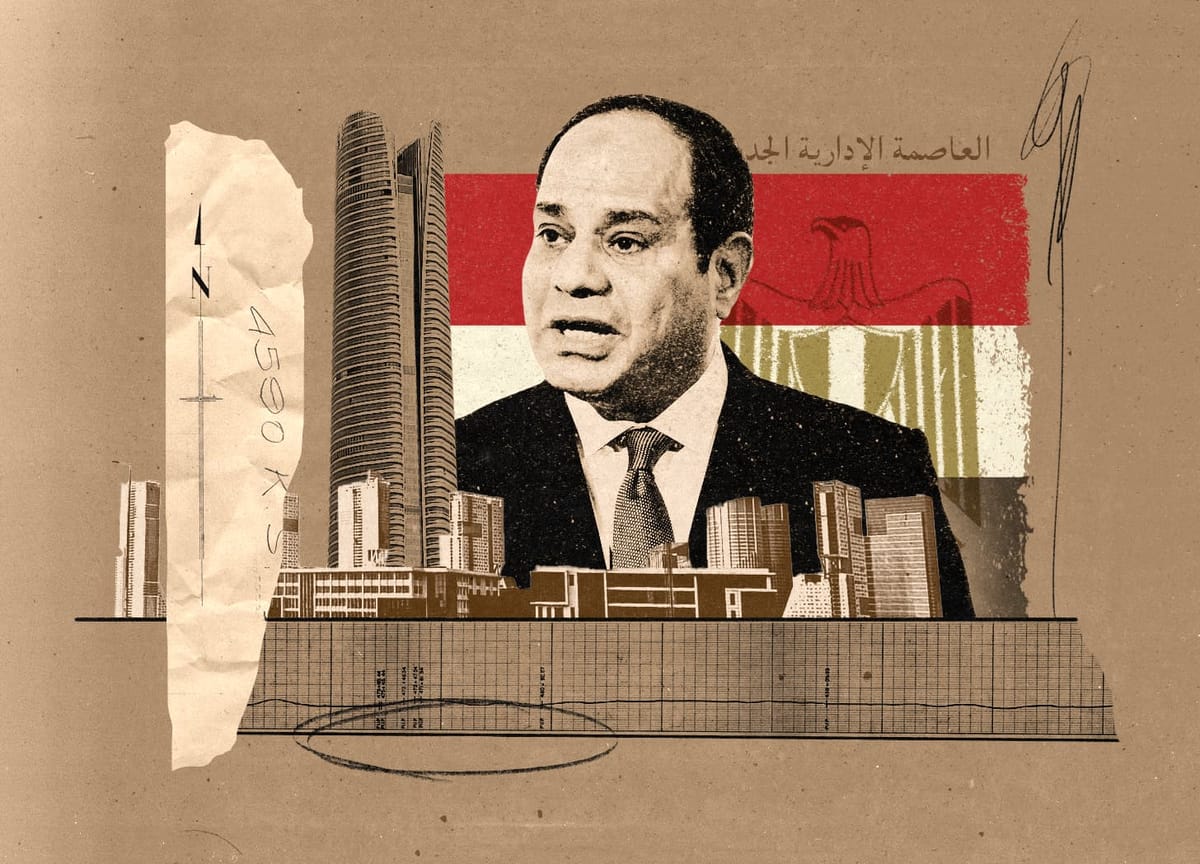

In Egypt, President Sisi speed-runs nearly two centuries of urban-planning ideas in service of his political agenda

Hi everyone,

This week, a brief introduction to the development of Egypt’s New Administrative Capital on the outskirts of Cairo. It’s urban planning on a scale seen only a few times each century. And though it’s emerging in fundamentally different political, social, and economic contexts than the ones most Frontier Magazine readers live in, I’ve been intrigued to see what principles and ideas familiar to me are being employed there. Peeks into other urban cultures, even those limited by language access, are fascinating and instructive. This one mashes up examples and lessons from the 1850s to current “smart city” efforts.

Until next week,

Brian

Takeaways from this week’s story

- 19th-c. planning: Like Baron von Haussman in Paris, Sisi is clearing out and widening the streets around Tahrir Square, the site of protests, and by moving government offices he’s trying to drain it of political significance

- 20th-c. power projection: Sisi is using expensive, showy “modernization” projects to imply national progress at a moment of economic turmoil

- 21st-c. funding and tech: The New Administrative Capital is being built primarily with funds from Western nations, the IMF, and increasingly China; “smart” and “green” tech—and lots of surveillance cameras—are one result

🔗️ Good links

- 👀🏢 Buildings that caught my eye this week: Peris+Toral’s social-housing complex in Cornellà, Spain (2021); Bucher Bründler’s new mid-rise residential development in Basel; and a three-firm collaboration on timber housing for students and seniors in Sweden

- 🚶🏻♀️➡️🏛️ Sean Marshall asks: in the Greater Toronto Area’s cities and towns, can you walk to city hall?

- ⏳⏳ A richly multimedia story: “Can Singapore rethink its reliance on sand for land reclamation and development?”

- 📣🙅🏻 “Criticism is now widely seen as a form of hate-speech,” suggests Australian architecture critic Elizabeth Farrelly in this defense of the form

- 💦🏠 An excerpt from the The State of Housing Design 2023 about “working with water”

Eastern Promises

Earlier this year, in the desert east of Cairo, families began moving into a city that does not yet have a name. Dubbed the New Administrative Capital, this mega-project was announced by President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi nearly a decade ago, and continues a long tradition of building new centers on the capital’s outskirts (e.g., Nasr City, Sadat City). Sisi’s project is breathtaking in its scale: “It is being built on 170,000 acres about 28 miles (about 45 kilometers) east of Cairo and nearly twice its size. It is planned to house 6.5 million people.” One of Sisi’s stated goals is to rehouse government and military offices, and administrative departments began moving into the new city throughout 2023. The other goal is to reduce overcrowding in the capital, where about twenty percent of the country’s hundred million residents live, more than half of them in informal neighborhoods that Sisi has vowed to eradicate by 2030.

What strikes me about the project, as I’ve read about it with increasing frequency in the last two or three years, is how it it embodies principles from three different centuries. The urban planning, in both Cairo and the NAC, superimposes “smart” technologies and “green” bromides onto a nineteenth-century approach reminiscent of Napoleon III and Baron von Haussman: clear out working-class areas under the guise of health and public space; install wider streets that are harder for protesters to barricade or occupy and easier for police and military equipment to traverse; and use grand built forms as symbols of power. The parallel comes to mind not least because Napoleon III came to power after the French Revolution of 1848 and Sisi came to power after protests in 2011, centered on Tahrir Square, deposed Hosni Mubarak and protests in 2013 gave him the opportunity to overthrow Mohamed Morsi.

In both cases, and many others besides, a new leader transforms a site of protest to decrease the likelihood of further uprisings. As one informative video notes, “They’ve widened dozens of streets, making it more difficult to erect roadblocks. And they plan to add forty bridges, which will give the military and police easier access to the city center. Sisi’s government has also renovated Tahrir Square, adding giant monuments and private security guards which, some experts say, will make it harder for large crowds to gather. Now, they’re taking the final step: removing the government entirely from Cairo.”

The scale of the NAC, and the other modernization projects that it joins, suggests the priorities of many twentieth-century leaders, in Africa and elsewhere: a projection of capability and power meant for international audiences as much as ones at home. Sadat City, mentioned above, was part of then Egyptian president Anwar Sadat’s plan to build numerous industrial cities during the 1970s. Sisi’s NAC is just the largest of a suite of projects, including an attempt to enhance the Suez Canal’s role in international trade, that is reshaping Egypt’s relationship to other countries. The German company Siemens built a high-speed electric train; Belgian construction firm Besix is working to build the Grand Egyptian Museum in Giza; the Russian state agency Rosatom is building a nuclear power plant along the Mediterranean coast. The NAC’s roughly $58 billion price tag is being underwritten not only by longtime aid partners like these, and IMF loans, but also newer entrants like China.

Finally, the vision Sisi is promoting is drawn from the twenty-first-century smart-city playbook. As the New York Times put it, “computer renderings envision verdant boulevards, humming tram lines and the extensive use of digital technology: Some 6,000 cameras will monitor the streets of the new city; the authorities will use artificial intelligence to optimize water use and waste management; and residents will submit complaints using a mobile app.”

Aging infrastructure and overcrowding of the kind now seen in Cairo can be dealt with, especially when one yields autocratic power. The huge investment in the New Administrative Capital could have been put in to housing, to modernizing infrastructure, to the creation of public spaces, and to social and economic projects that support the most vulnerable populations. Instead, according to the Wall Street Journal, “the cost of an apartment starts at around $80,000. In 2020, the average household income in an urban community was just over $2,600.” It’s clear, Steven A. Cook writes, “The new city is not being built for average Egyptians. It is set to be an exclusive compound for government workers, senior officials, and other elites.”

As of this writing, there are 7,802 properties for sale in the NAC—properties built by a company that is owned 51% by the military and 49% by the housing ministry. There are new listings every few hours. And, as Belgian photographer Nick Hannes’s book New Capital makes clear, these kinds of changes have recently or are currently taking place in other countries, too: in Nigeria, Abuja replaced Lagos as the capital in the early 1990s; in Kazakhstan, Astana replaced Almaty as the capital in 1997; in South Korea, Sejong was founded in 2007 and administrators began moving from Seoul in 2012; and in Indonesia, Nusantara is scheduled to be inaugurated on August 17. What will these places’ successes and failures reflect back to us as we think about and reshape the cities we live in?