Engaged by Design

A different way of thinking about public engagement

A few years ago I was part of a stakeholder-engagement session for a big waterfront project in Toronto with about fifteen members of the local community. We’d set up in a pretty generic room in a downtown university building that overlooked a nearby rooftop urban farm that was an example of the kind of project we were gathered to discuss.

We’d put up large boards on the walls and provided colourful decals that aligned with the variety of themes we were discussing. It wasn’t a particularly spirited discussion. We dutifully worked through a set of questions, prompts, and opportunities together and slowly filled the boards with location-specific ideas for what will eventually become a pretty epic rooftop community garden and urban farm.

The experience was typical of the kinds of public and community engagement projects we are involved with and featured the usual challenges—including the fact that the rooftop had been largely designed already. The input we were receiving was hard to see as anything other than performative.

Such is the nature of public engagement for many design projects.

Two Scenarios

The typical engagement process for architecture, urban planning, and landscape architecture projects follows one of two scenarios.

The first involves some engagement with the public that could be at different scales. At the smallest, it may be a handful of community or strategic stakeholders. At the largest, it can be a big public meeting that invites anyone from the local community who would like to have a say on an upcoming project. In this scenario, questions are put to the group along with opportunities for them to provide input. The harsh reality is that the input then typically goes into some form of report that is handed over to a design team that largely ignores it as they apply their expertise to the project at hand.

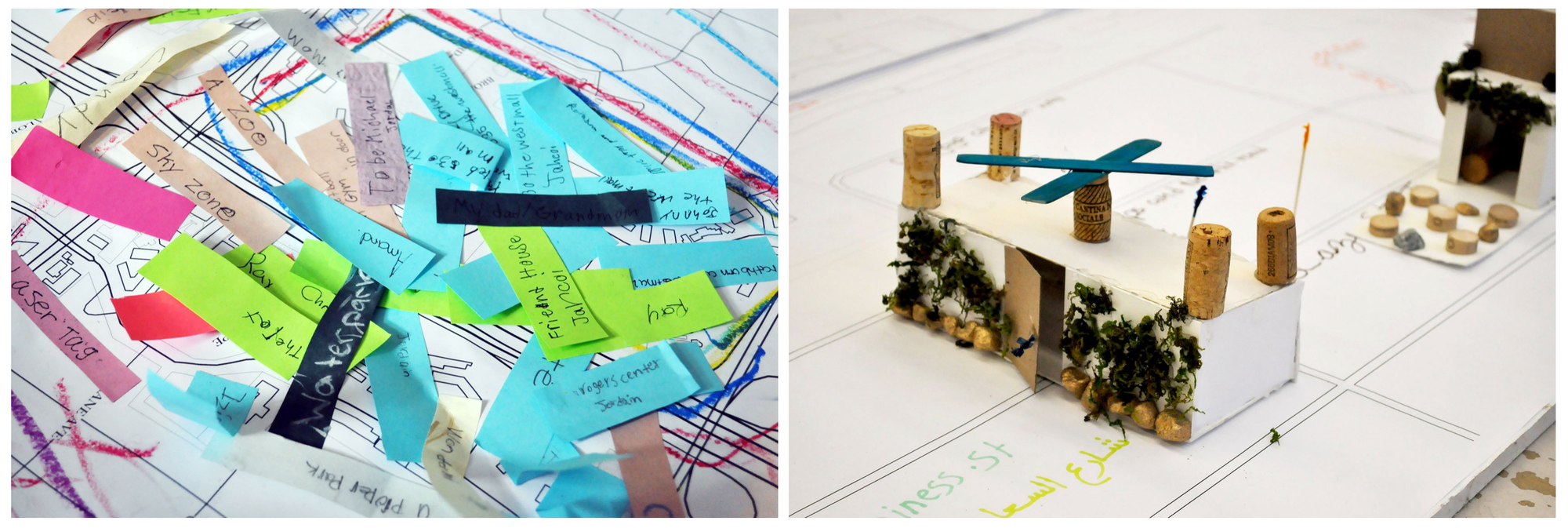

The second scenario involves an initial design concept that has already been prepared. An engagement team takes that design and uses it as a reference point for the stakeholder group. A process, often involving Post-it notes, takes place and ideas are added to the existing design, whether it’s a building, a landscape, or something else altogether. Once the workshop is done, the engagement team synthesizes and packages the content and hands it over to the design team, who largely ignore it as they apply their expertise to the project at hand.

In both cases, the input, at best, surfaces an interesting insight or two. At worst, it’s a waste of time for all involved.

Of course there are more productive versions of the above, but the two scenarios represent the norm. And of course there is great value in engaging communities for input on something that may fundamentally change where they live. The question is: Can it be better?

Lost in Translation

Part of why the engagement process is lacking is because design can be impenetrable. For the average person, critical considerations at the heart of a design project are not legible. Pedestrian flows, constructibility, budget awareness, and even taste are knowledge hard-earned by designers through years of education and practice. We do not do public consultation for surgery. We do not do public consultation for engineering. But we do invite participation and input for design projects.

To be clear, we must invite participation, but we must also recognize its limitations. We should design the process to be more relatable to those providing input and more generative and useful for the designers (architects, urban planners, landscape architects) responsible for applying that input.

Common Ground

Christopher Alexander’s A Pattern Language offers a perspective on this handoff. He uses ideas like “Light on Two Sides of Every Room” as a way to describe a desirable characteristic of a space. The problem he identifies is that rooms lit from only one side are dull and flat. The solution is to design rooms with natural light coming from at least two directions. This idea is relatable. Anyone gets it. You don’t have to understand photometric calculations, building codes, or energy regulations to understand that a room with light on two sides is a nicer room to inhabit.

Alexander is using simple stories to guide us toward good design.

Stories are relatable tools. They provide a bridge to common ground between community members and designers. Everyone understands the elements of a good story, and so good public engagement should start there, with questions like: What stories do you have about this place? What is something meaningful to you about this place? Those stories can be highly personal. They can be about specific moments in a person’s life. In fact, the more personal and specific, the better. Tools that provide communities with space to identify and locate personal stories in their neighbourhoods offer a simple way to connect people to the project.

So what does it look like if engagement is driven by a story first approach? What do story driven places look like?

Story Places

While stories offer a simple and understandable starting place for engagement, they are not an end in themselves. They are seeds for inspiration. Examples of powerful story-driven spaces help provide inspiration for the kinds of stories that shape spaces. Offering references to these examples can offer guidance for what a new space might become.

Think about Maya Lin’s National Mall Vietnam Memorial in Washington, DC. The space is exponentially more powerful because of the names inscribed on the wall of the 58,281 United States service members who died in or remain missing from the Vietnam War. Without that story, the space has nowhere near the meaning or impact.

The form of the space itself helps to reinforce and strengthen its meaning. The names were the central design element guiding Lin’s concept. Arranged chronologically by date of death, they shape the memorial’s descending V-shape form, leading visitors through the timeline of the war. The reflective surface juxtaposes the visitor’s own reflection against the sheer volume of names, and transform the space from a static monument into a participatory narrative—a place where memory, grief, and time are made physically and emotionally tangible.

Churches are embodied stories. Being in those spaces is the perfect synthesis of architecture and meaning. A powerful example is the Kaaba in Mecca, Saudi Arabia—one of the most sacred spaces in Islam. The Kaaba’s simple cuboid structure is not architecturally complex, but it is saturated with narrative meaning: it is believed to have been built by Abraham and his son Ishmael as the first house of worship to one God. That origin story shapes every aspect of its spatial role—from the direction of prayer (qibla) for Muslims worldwide to the ritual of circumambulation (tawaf) during Hajj, which reenacts the stories of devotion and sacrifice tied to Abraham’s faith.

The space itself is minimal, but the narrative layers—of lineage, obedience, migration, and divine covenant—are what generate its power, making the Kaaba a prime example of a story-place where narrative is not decoration but structure, function, and ritual logic.

New York’s High Line contains traces of its story, its history, in the design. Diller & Scofidio imbued story into the material design of the space. From its origin as an elevated train line and to its evolution into an abandoned piece of infrastructure where nature pushed its way into and through its structure to its new life as a public space that connects the city and provides a unique urban experience, the High Line is a space made into a place through the stories of its past, present, and future.

A Beginning but Not an Ending

Stories are not enough. Once gathered, it takes talent and ability to transform them into space with meaning … into a place. A good designer can envision a novel form for a space. A great designer transforms genuine stories into places of meaning.

Places of meaning are valuable. Through higher lease rates, resale value, and foot traffic, The High Line has generated an estimated $2 billion in adjacent real-estate value over a decade.

Teshima Art Museum and the Benesse Art Site Naoshima have used deeply curated narrative experiences to attract global cultural tourism—despite being remote. This has sustained long-term tourism revenue and led to national recognition.

Evergreen Brick Works in Toronto used narrative-driven placemaking to integrate ecological, industrial, and Indigenous stories—leading to community alignment and stable philanthropic and public investment.

Even retail spaces like Aesop stores or Starbucks concept locations with embedded local narratives see higher linger time and higher average basket size than generic locations.

The key is in the moment of translation. Where public engagement often falls down, the moment between input and design, is where the opportunities lie. If we can design the process to both create an environment for accessible and meaningful story-driven input so that it provides creative energy for design teams with the talent to translate story into design—well, then we start to see real value. The goal is to take stories and turn them into meaningful and inspiring spatial concepts. This is the moment where stakeholders and designers require a new translation structure.

Even in a process where the design is “done,” a story-driven approach offers opportunities for a layer of interpretation, programming, or intervention that adds significance and meaning that will enhance the project.

The Future of Engagement

The Story Place approach to engagement and design attempts to bring meaning both downstream to the people we are engaging with and upstream to the designers who are tasked with bringing a space to life. It offers a way of thinking about space that demands engagement with the stories that float invisibly in and around it. It gives a way for people who may not have the education, experience, or expertise to deal with the practicalities of design a way to provide perspectives that are meaningful to them while providing useful creative input for design teams.

Importantly, this approach can scale. It works for the most significant religious spaces on earth as well as for the smallest local community parks. The point is not the scale, it’s the uncovering and celebrating the meaning unique to the space.

The more we can add meaning to the spaces we design, the more connected we will feel to the places we live.

📕 Narrating Space/Spatializing Narrative

⠿ A Pattern Language

🌊 Theory of Water