Enough Is Enough

On sufficiency and upfront carbon, through Lloyd Alter’s new book

Hi everyone,

This week, I’m rethinking a lot of choices in light of Lloyd Alter’s engaging new book The Story of Upfront Carbon. If you’re intrigued by my review below, consider subscribing to his Carbon Upfront! newsletter. Hit reply or drop a comment below to tell me about a lifestyle change you’ve recently made with sustainability in mind.

Until next week,

Brian

Takeaways from this week’s issue

- It’s carbon all the way down. No matter how efficient our products, no matter how renewable our energy, it all comes with a carbon cost.

- Rethinking buildings and transport offers the greatest chance for positive impact. They account for ~75% of American carbon emissions and require a fundamental reorientation.

- Increasing efficiency is not enough. We must choose what sufficient looks like and adjust our lives to that standard.

🔗️ Good links

- 👀🏢 Buildings that caught my eye this week: Beau Architects’ gallery in a Hong Kong tenement house; Parallel Studio’s library for young students in Zanzibar; UAD’s rooftop soccer field for Shaoxing University

- 🔋🚲 Japan-based American writer Craig Mod on e-bikes, the “stupid love of my life”

- 🔨🪛 Oliver Wainwright on “a miraculous 15-year self-build that promises capped-price housing for ever”

- 🛣️🚫 “Colorado’s bold new approach to highways—not building them”

- 📽️🏝️ Last January, I wrote about DnA’s repurposing of abandoned quarries; now the Canadian Centre for Architecture in Montreal presents a film exhibition documenting principal Xu Tiantian’s approach to an island museum project

Enough Is Enough

Fifty years ago, argues Lloyd Alter, “the energy that it took to make things wasn’t seen as a big issue.” In North America, that was because “major industrial processes such as making electricity, steel, or concrete used coal, not oil, and it was not imported, so it didn’t matter.” After oil prices began dropping in the early 1980s, even the modest sustainability gains of the ’70s fell out of public consciousness. (The solar panels Jimmy Carter installed on the White House roof in 1979 were removed in 1986.) We started along a path toward supersize cars parked in the garages of supersize homes on supersize suburban lots.

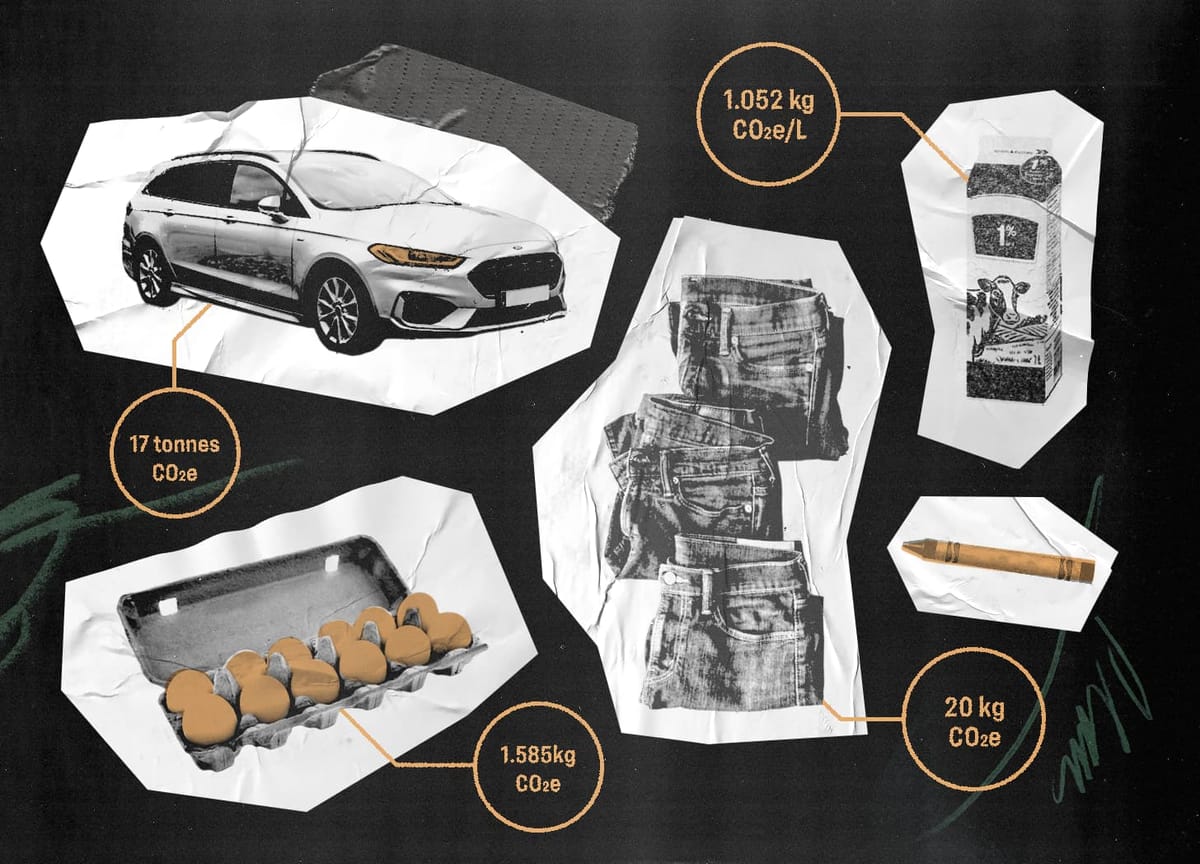

Alter, an architect and journalist, has written The Story of Upfront Carbon (buy in the US or Canada) to chart a revolution in thinking that is only now taking hold: “When you look at the world through the lens of upfront carbon, everything changes.” Upfront carbon, the term, refers to how much carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases were emitted while making a product. It’s familiar to architects and builders as the first part of a life-cycle assessment, which measures greenhouse gases from “cradle to grave.” It’s the precursor to operational carbon—the thing we, as consumers, buy offsets to counteract. And as we get better about mitigating operational carbon, upfront carbon is the thing we’ll be talking about more. Alter suggests this is an “ironclad rule”: “As our buildings and everything we make become more efficient and we decarbonize the electricity supply, emissions from embodied and upfront carbon will increasingly dominate and approach 100 percent of emissions.” In other words, we’ll only have upfront carbon to worry about.

The challenge, of course, is that it’s a big worry. Thinking about operational carbon is like standing before a mirror: we see ourselves, the things we make, and our choices and actions in a new way. We realize that running the washing machine on a hot cycle has a greater environmental cost than a cold cycle, and a dryer is worse than a clothesline. Adding upfront carbon to the mix is like adding a mirror behind us, creating an infinity effect: it’s carbon all the way down. Making something comes with an environmental cost, using it comes with a cost, even recycling it comes with a cost. As Alter notes of the increasingly popular concept of the circular economy: “You can’t fight the laws of thermodynamics; it took energy to put the original product together, and because of the tendency to increasing entropy and disorder, it takes more energy to make it circular.”

Are we doomed? There are certainly people who think so. But the book’s subtitle also promises “a way out of the climate crisis.” Because “unlike operating carbon emissions, where efficiency rules, dealing with upfront carbon emissions is all about sufficiency, about using less of everything, because everything has a footprint.” The answer is … us, and our choices. Whether this is good news depends on your faith in people.

More specifically, Alter notes that our environmental crisis is presently a rich-world problem, and that two of the sectors where we can have the greatest impact are building and transport. Today in the United States, he notes, buildings and cars account for about three-quarters of carbon emissions. So while he discusses other consumer items, like coffee cups and puffer jackets, his primary focus is on how we live and how we get around.

Citing scholars and practitioners, Alter argues that, through the lens of upfront carbon, “the greenest building will be not too tall, made of wood, and a boxy simple form with windows designed to frame a view, not to make a statement.” But a look around Toronto, where Alter and I both live, reveals how few such buildings exist here. Instead, we have glassy condo towers and single-family homes. That’s why “the single biggest factor in the carbon footprint in our cities isn’t the amount of insulation in our walls, it’s the zoning.”

Similarly, Alter convincingly argues that we can’t just swap gas-powered cars for their electric counterparts; there isn’t enough lithium, and all that mining, again, has an upfront cost. But “it’s not just the vehicles, but the roads they drive on, the parking garages they sit in, the sprawling development they make possible,” and other accommodations they require. We need denser, more compact cities and the transport infrastructure that increases the use of cargo e-bikes, for which Alter professes his love, and decreases the need for cars.

The Story of Upfront Carbon is an eye-opening primer. And midway through, Alter hits on the crucial question of what comes next: “Defining what is enough and how much one needs is going to become a critical issue in the discussion of upfront carbon.” That debate is rhetorical and political more than it is scientific or design-focused. What stories galvanize action? What is the upfront-carbon version of Michael Pollan’s food manifesto? New technologies are already coming to save us. Will we join in the cause to make sure they’re successful?