For the Time, Being

The designers behind CW&T talk about making long-lasting objects and reconceiving our relationship to time

For more than a decade, Taylor Levy and Che-Wei Wang, the Brooklyn-based product designers behind CW&T, have made carefully crafted objects that quietly transform their surroundings. We spoke with them about shifting our awareness of time, over-engineering their products, and deliberately staying small.

Brian Sholis: I’d like to begin with Superlocal, your latest project. Can you describe the clock and how it ties in to your thinking about routines, rituals, and mental and physical health?

Che-Wei Wang: Superlocal is, in some sense, an accident. We had prototyped many small wall clocks. Then our kids kept waking us up too early, so we took a prototype and put two stickers on it and said, “This one is when you can wake us up on weekdays, and this one is for weekends.” That became a lightbulb moment: the time itself didn’t matter, it was only when the hands passed the stickers. How else could something like that look? So we prototyped one that has dimples for magnets, and saw how it relates to another ritual of ours. Every few years, we make a pie chart wherein each slice represents roughly how we spend our time, then we make a second chart that represents how we wish we could spend our time. Sometimes they’re similar, sometimes they’re wildly different. But we began thinking about how a clock could reinforce your rituals, or gently nudge you toward your ideals.

I think a lot of people cannot properly envision their days. We’re too busy looking at calendars—year, month, week—that present information in linear form. We rarely see things in twenty-four-hour cycles, or account for just how much time we spend asleep. We believe it’s nice for an object to give us a cyclical perspective on our lives.

BS: You have made about half a dozen clock- and time-measuring projects over the past decade. Can you talk about your interest in and the relationships among time, timeliness, and timelessness?

Taylor Levy: One way we think about these tools—such as Time Since Launch, which counts for 2,738 years from a moment of your choosing—is that they help you regain ownership over something that has largely been taken away from you. Time zones were invented for railroad companies; your weekly calendar is likely governed by your work schedule. Time Since Launch gives you a single moment, whatever that moment is, and places it in relationship to one million days. There aren’t many things you walk past on a day-to-day basis that give you that frame of mind.

CWW: In making these time pieces, and in writing two academic theses about time-keeping, the way I think about our relationship to time has shifted. When I began making these devices, I felt how I believe a lot of people feel: I wanted to escape the pressures of time, to live in the moment. I kept asking whether we could shift to different methods of time-keeping, different tempos.

Now I tend to believe the pressure we feel with regard to time is because our perception of time’s duration is distorted. I’m curious about how we can become better tuned, so to speak. Athletes, for example Formula 1 drivers, are often put through exercises to help them in this regard, to eliminate how bodily fluctuations affect their sense of time. We’re constantly trying to predict how long things will take, or how long we think we’re spending on tasks. Being bad at that causes anxiety. I want to hone my sense of time so it’s more closely tied with reality—and thereby to feel less anxious about time itself.

BS: Continuing on that theme, your company’s principles include “make it last,” which discusses how quality ensures objects can last, and “never exit,” which mentions how you feel what you’re doing is your life’s work. Can you talk about how those two versions of longevity are related?

CWW: It’s so frustrating to buy something and have it not last as long as you expect it to. It seems like the overwhelming majority of the world’s manufacturers have gone the route of saving money by value engineering objects. We are explicitly against that. We want things to last—beyond your lifetime, if possible.

TL: I sometimes feel tentative about putting objects into someone’s life. If we’re going to do it, we’re going to do it for the proper reason, and that object should last as long as that reason is valid. If that means it costs us more money to make it, or that the customer has to pay more for it, so be it. Its lifetime value will be greater for that.

CWW: The saddest thing is for anything we make to end up in a landfill, ever.

TL: CW&T is itself just a container for our creative practice. Sometimes we make a piece of software, sometimes a painting, sometimes a tool or a toy we want to use around the house. We don’t think of it as a large or growing endeavor, but rather as a sustainable practice that allows us to be creative, supports our family, and gives us a way to relate to a community.

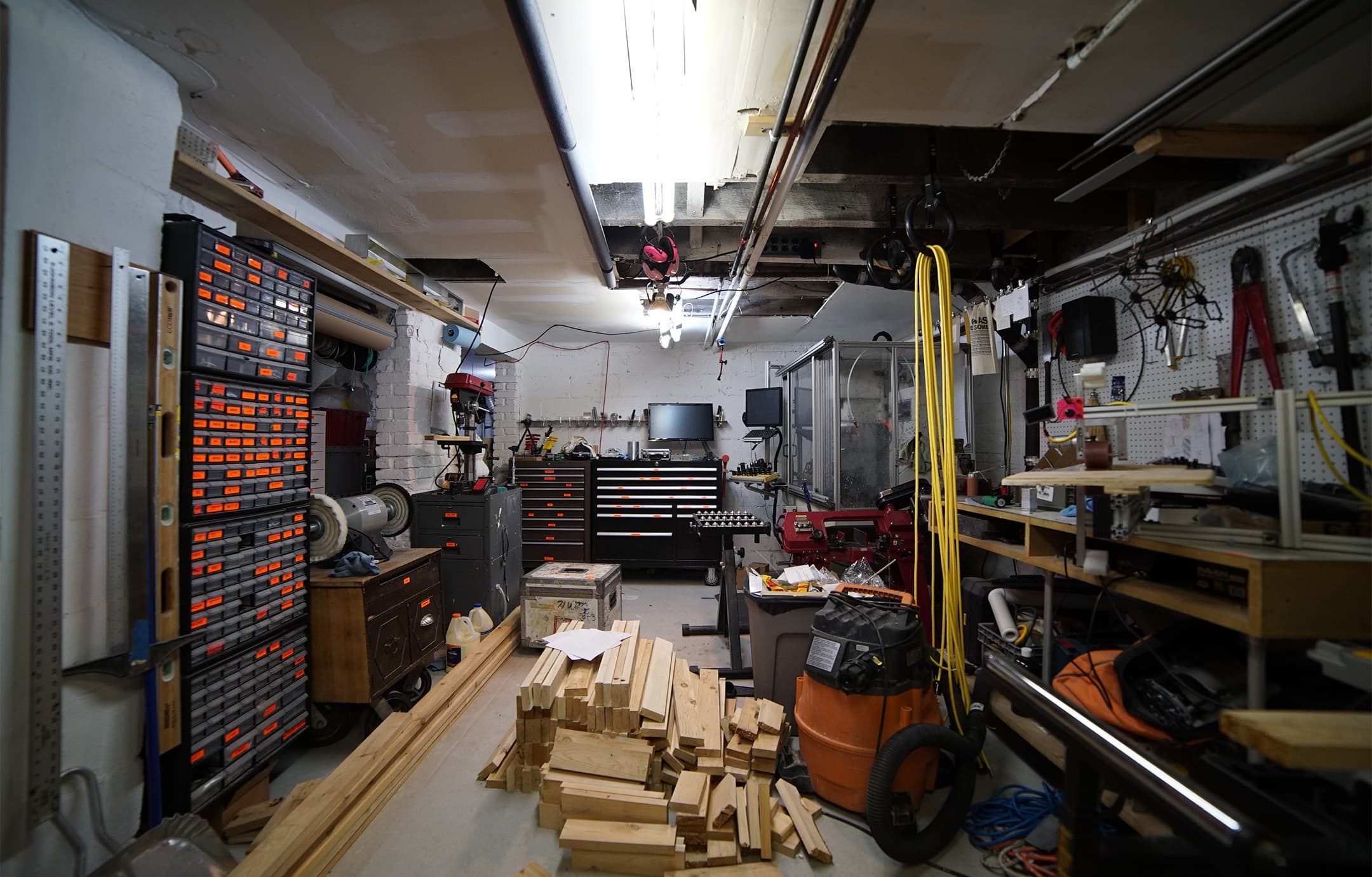

We came into being at the perfect time, just as internet tools like ecommerce and social media were blossoming. They enable us to be independent and to have agency over what we make. We’re not special; we’re just lucky to be working at this moment. We were one of the earliest designers to use Kickstarter. At the same time, Che-Wei was courageous enough to have prototypes made overseas and shipped back to us. We’ve benefitted from an amazing confluence of technologies and capabilities.

BS: You’ve mentioned wanting your objects to give “positive emotional experiences.” Can you talk about how you account for that when designing?

CWW: Ninety-nine percent of what we make doesn’t go out into the world, and that’s partly due to the fact that both of us have to agree—we both have to connect with an object in a useful way.

TL: As part of a game a friend recently asked, “What’s your superpower?” Mine might be that I’m very sensitive, that I can connect with objects on a visceral level. So if my experience isn’t totally positive, we tweak and tweak until it works. We never rush things into the world; we aren’t launching based on calendars or expectations. Everything has to be just right.