From Strategy to Startegy

How artful thinking pushes collective progress.

When speaking with a class of architecture students last week, I introduced a few workshop exercises our team uses to help clients uncover their strategic story—the essence of who they are and what they do. One exercise, called “I am for a ...,” is based on a poem by artist Claes Oldenburg called “I Am for an Art….” In it, Oldenburg writes over sixty descriptions and declarations of what he believes art should mean.

We use this poem for the exercise because it helps participants open their frame of thinking for the question we are about to ask them: What do you believe your organization should stand for? Without it, we often get answers like: “I am for an [organization name] that helps people.” We often end up with many mundane and uninspired imaginings.

At the end of my talk, I asked the students to complete the following sentence: “I am for architecture that ...”

The answers were heartening. Among the responses:

“I am for an architecture that listens and only talks when it has something worth saying.”

“… is not just functional but is kind.”

“I am for architecture that comforts with soft materials, flowing curves, and therapeutic environments—spaces for healing, not just shelter.”

The framing of the exercise, if successful, results in these kinds of unexpected answers. And unexpected answers are more memorable, effective, and evocative. They “stick.” Why does this matter? A few reasons.

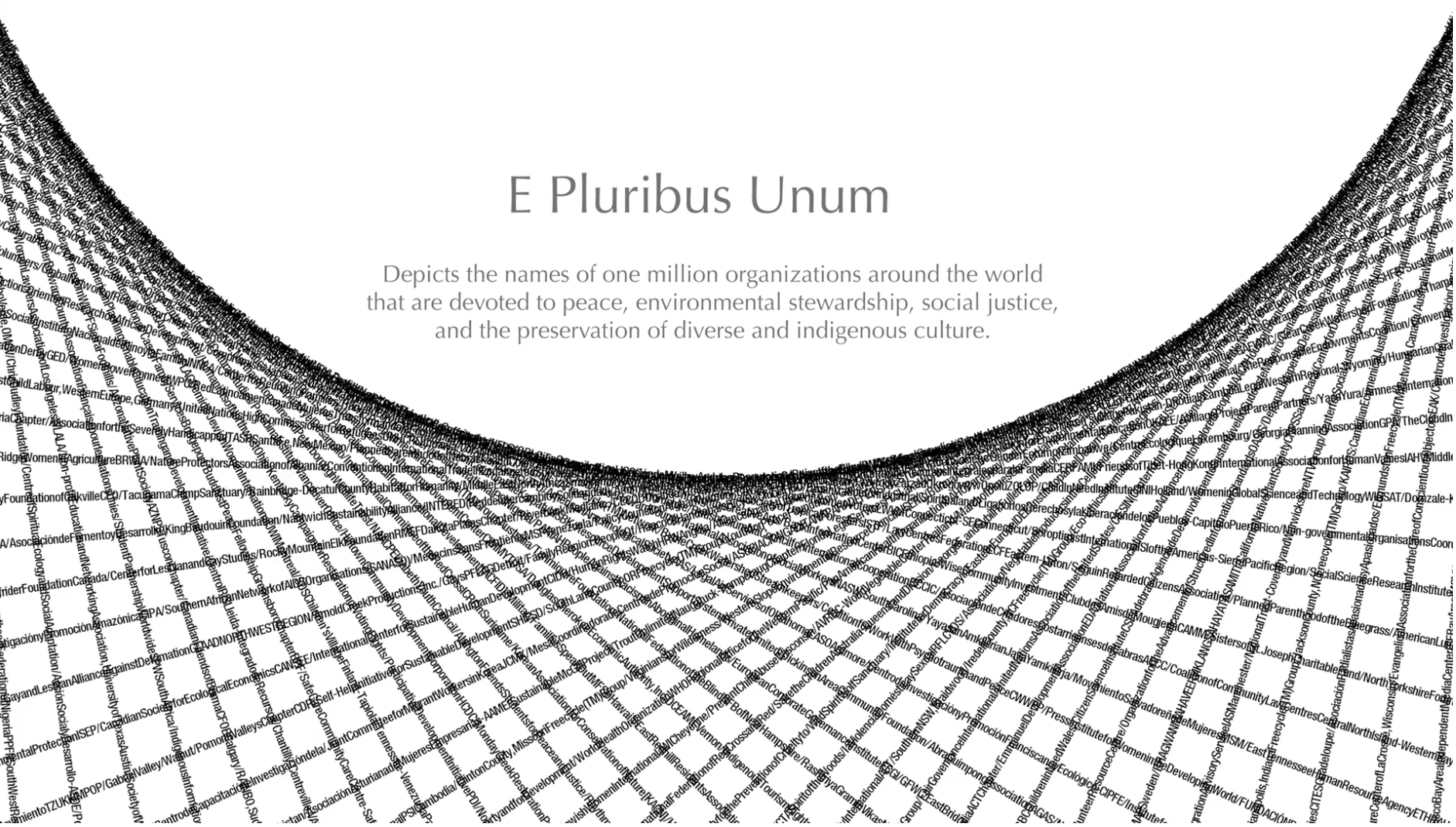

Several forms of US currency contain the statement: E pluribus unum, which is Latin for “Out of many, one.” The phrase speaks to the idea that the United States is a collection of parts that, when united, form a stronger whole. In the twenty-first century, an age of networked and exponential technology, the new aspiration might be: E pluribus plura. Out of many, more. While it’s a struggle to see it now, it should be that our numbers amplify our effect. Aligned groups of individuals can achieve more than individuals alone.

This network impact has both positive and negative implications. The negatives are apparent in the work of Chris Jordan, whose constructed images visualize quantities that are too large for our understanding. But one of his works, called E pluribus unum, visualizes the power of networks. It depicts the more than one million organizations working on environmental and social-justice causes around the world. In a time where it’s easy to despair, it’s worth a look to see exactly what one million really means.

This network effect applies at a range of scales. The key is alignment. Stories align people around shared goals. Being deliberate in the construction of that story helps ensure the alignment bit. But being artful helps people get their emotional brains into it.

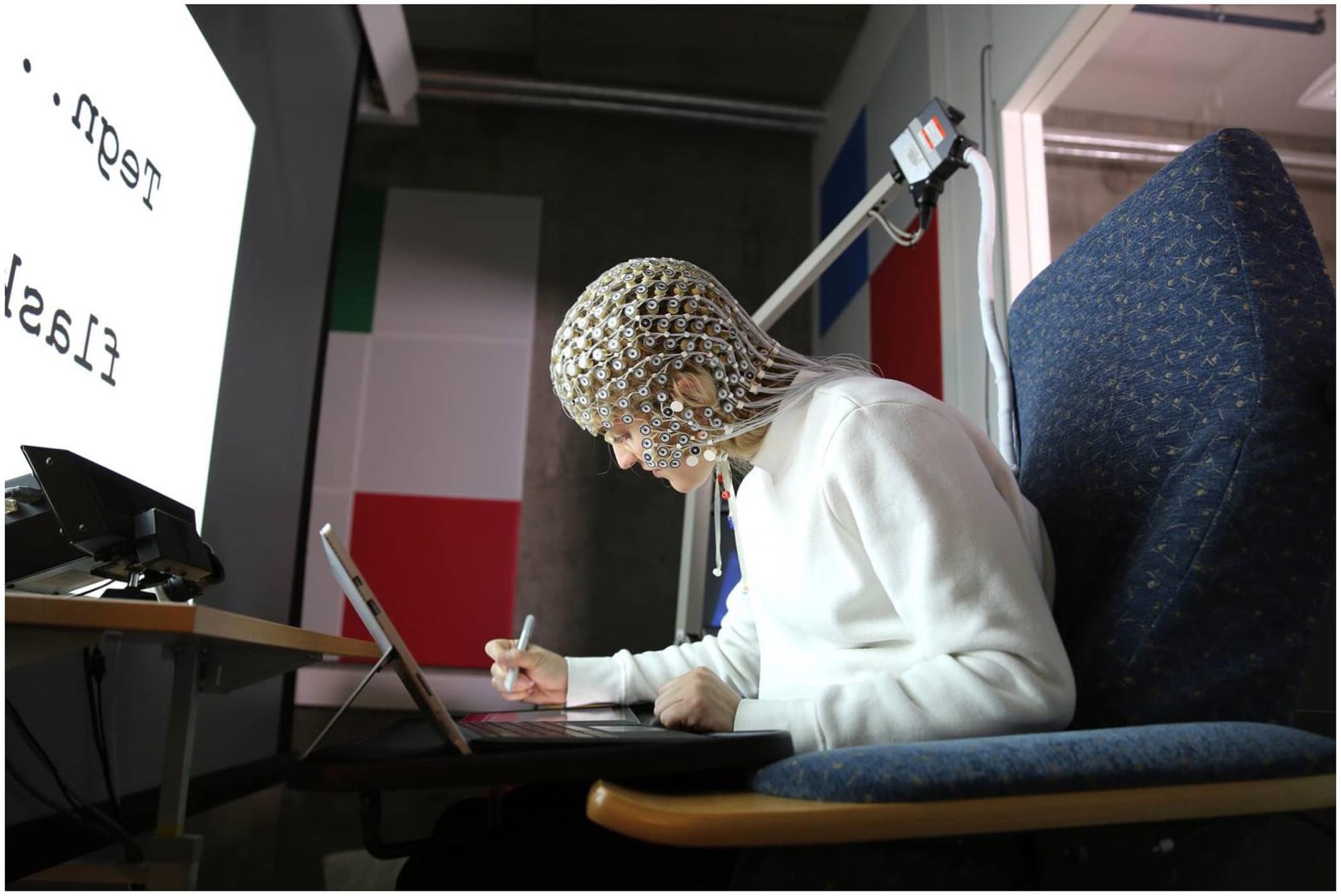

A 2017 study in Frontiers in Psychology showed that students who drew concepts rather than just reading or writing them had much better memory retention.

Participants were given a list of simple words like apple, balloon, and desk. For each, they were asked to draw, silently visualize, or write out the word repeatedly. They were then asked to recall as many words as they could after a short delay.

Participants remembered nearly twice as many words when they drew them compared to when they wrote them. Even those who were “bad at drawing” succeeded in remembering the words more effectively, even when the drawings were very simple.

It’s the combination of visual, motor, and semantic encoding involved in drawing that helped them remember the list better than other forms of memorization. This idea of thinking with your hands, or “whole body learning,” is something most professional “creatives” understand. For those who grew up drawing, most will recall how drawing an object is a wonderful way of more deeply understanding it.

The same is true for organizational strategy. The more we can infuse art and creative practices into business-driven activities, the better the chances at retention and realization of the strategy across the organization.

Yet we’ve built a world that marginalizes art and creative practices as the domain of “creatives”—I hope the scare quotes show how I hate that word and the reductive categorization it implies—and pushes these kinds of thinking to the margins.

Singer and author Tanya Tagaq’s Retribution is “not entertainment; it’s resistance.” Through traditional Inuit throat singing, her political narratives call out colonial violence and environmental destruction. Her performances become points of focus at events like Idle no More and have mobilized Indigenous as well as non-Indigenous audiences through the experience of art in a way that a highly rational argument laid out in a soberly delivered speech can never hope to do.

Tanya Tagaq’s Retribution

It’s not controversial that, collectively, we’re up against significant systemic challenges. If we want to achieve wide progress at scale, then it helps to recognize features of our culture that have been under-leveraged by mainstream rationalism for the better part of a century. It takes understanding that impact comes with aligning communities of people. It takes a willingness to be open to an understanding of how art and creativity (and design) can be a means to help internalize a shared purpose and ambition. And it takes a belief that strategic narrative and story can be the roadmap that guides the change.

Barb Groth's Nomadic School of Wonder is wholly devoted to helping people experience life with more immediacy through art and art practice. Working with companies like Google, AirBNB, and others, her belief is that a state of wonder helps us more profoundly internalize our experiences in a way that can heal and help us in our day to day lives. Her current project focuses on Ernest Hemingways' novel, A Moveable Feast, and engages participants in a series of creative exercises based on Hemingway's life in 1920s Paris. Full disclosure, we worked with Barb to help make a physical manifestation of the experience in the form of an Adventure Kit that provides tools like notepads, lucky charms, and maps of the Paris that he would have explored, that help facilitate artful thinking.

The Nomadic School of Wonder creates a space for artful thinking so rarely found in our highly connected and never off lives. The desire for a window into this kind of experience has found traction in the most forward thinking mega companies because our experience structurally discourages it.

Maybe it’s time to bring art into strategy. Maybe its time for something new that not only engages us emotionally but also gives progressive movements a new way to begin. Maybe it’s time for Startegy.