I’m a Designer

But what does that even mean?

I was at a corporate event last week frantically working away in a corner of the lobby with a half-eaten stale croissant on a small plate when I overheard a conversation between two employees of an HR software company. One was talking about the design of something they were working on. The other person, apparently more senior, asked: What kind of design?

My ears perked up. It’s not often that you hear discernment or nuance in the use of the word. Typically, the average person assumes it’s an effort related to picking colours and drawing shapes—you know, making things look good.

It can be strange to overhear people who are outside it talk about your sphere. The conversation went back and forth a little about how design can mean a lot of things. It turned out the more junior person was talking about UI (user interface) design. They were clear about the point of discussion, and moved on to other things.

Make It Pretty

“We’ll finish this first so that you can make it pretty” is a phrase you often hear if you’re a designer working around others who are not. The thing they are finishing first is often the “work.” It’s the thinking, the strategy, the business side of things. Only once that work has been completed can they move onto the next part, where the thing, which now exists, is made pretty.

I’ve been in countless conversations where context for the word design has meant vastly different things. In some cases, it’s meant “to make something pretty.” In others, it meant applying the methods of design to organizations so that they can work from a more user-centred approach. In one memorable instance, it meant reconceiving the master plan for the Holy City of Mecca in collaboration with an urban planner and about twenty teams of international engineering and architecture firms. And in yet other instances, it’s meant something more akin to marketing.

In fact, most people think that what I do is marketing. While there is some truth in this, I think it sells short the opportunity of design, in the broadest sense.

To Mark Out

Having studied literature and then architecture, my understanding of design is informed by my understanding of words. My method for clarifying just about anything is to start with the origin of a word.

The word design comes from the Latin “designare,” which is a combination of “de-,” a prefix meaning “out” or “from,” and “signare,” which means “to mark.” So the Latin root designare means “to mark out“ or “to designate.”

This is how I come to the idea of design. It’s the act of planning or making intention clear through symbolic or physical marking out. It’s essentially the act of proactively creating intention. Many professions deal with the world as it is. They are presented with a set of realities and their job is to work with those realities.

The kind of design that I am attracted to is about working with possibilities for what the world can become. Design school teaches students how to do this: to create something out of nothing. And while that’s a terrifying prospect for most, the goal of a good design education is to teach ways to carefully navigate the uncertainty of the unknown to reduce risk on the path to creating something new.

New What?

But what are we creating? Traditionally, designers create tangible things like buildings (architecture), logos (graphic design), websites (UX & UI designers), products (industrial designers), landscapes (landscape architects), and even cities (urban planners).

In every instance, the designer is applying the same tools: sketching, prototyping, modelling, storyboards, and more to create mock-ups and tests for the thing they are designing.

But there are emerging categories of design practice that use the same methodologies for more intangible outcomes. Experience designers conceive of entire experiences for “users” (a.k.a. people!). Service designers conceive of the path a person takes through a process (they fix, for example, the bad customer-service experiences you’ve had). Organizational designers structure teams, decision-making, and workflows. Brand designers create the positioning, values, and emotional resonance of a brand.

At Frontier, we espouse strategic story design, which begins with something akin to brand design but applies to far more than selling products and services and focuses more on meaning-making, transformation, and long-term narrative arcs.

Where It Lacks

There was a stretch in the late naughts and early 2010s when design had major traction beyond tangible outcomes. The phrase “design thinking” exploded onto the scene. Harvard Business Review and Stanford’s d.school helped promote its rise, and design firms like Frog and IDEO burst into public consciousness for products that took a more upstream approach to design.

Rather than just accepting that objects like vegetable peelers had been perfected, designers like Sam Farber, at SmartDesign, deployed tools like observational research and user testing with low-fidelity prototypes to transform everything from common kitchen utensils to the experience of how we give blood.

Suddenly design was in the boardroom, at the “big” table, rather than downstream making things look pretty. But soon, as in many places where new and unconventional ideas gain traction too quickly, people got sick of the concept of design thinking. Designers get bored very very quickly, and they were happy to send the phrase to an early grave.

And with good reason. Not all design and not all designers deploy the tools of design in the same way. Staunch protectors of the more traditional understanding of design are quick to reject the more conceptual framing of the term. For them, design is at its most valuable when it does focus on the tangible.

I once wrote an article about how Ricky Gervais was a designer when he reframed his television hosting duties at the Golden Globes and critiqued the entertainment industry. For me, he wasn’t only speaking to the people in that room on that night, but to a far wider audience of viewers at home who were fed up with Hollywood’s self-congratulatory culture. Thinking more broadly about your audience, and “marking out” a path that was more inclusive of the people who make that business possible, is an act of design.

But Erik Spiekermann disagreed. The renowned German typographer, designer, and author re-shared the post with the comment that Gervais is not a designer, he’s a comedian. And he’s right. But so was I.

Both, And

One technique of design thinking is to use “and” instead of “but.” The idea is to reframe every conversation as full of possibility rather than shutting it down with stultifying words.

While Gervais is, strictly speaking, a comedian, he is also a designer because he was refusing the status quo of platitudes and niceties that had been expected of awards-show hosts.

Design is, fundamentally, about possibility. It’s about seeing the world as more than what it is now, but/and what it could be. It’s about investing as much meaning as possible into the things we make so they are enduring and leave a situation better than when we found it.

And while tangible outcomes are often the most visceral and powerful results of good design, for it to be even more effective, the process should start far sooner “upstream.”

A Final Word

I’ve called for designers to transcend the business model they most often find themselves in. Designers typically provide services. That means that many key decisions have already been made by the time we’re involved. That mindset under leverages design to such a degree it’s like using an LLM to make a grocery list.

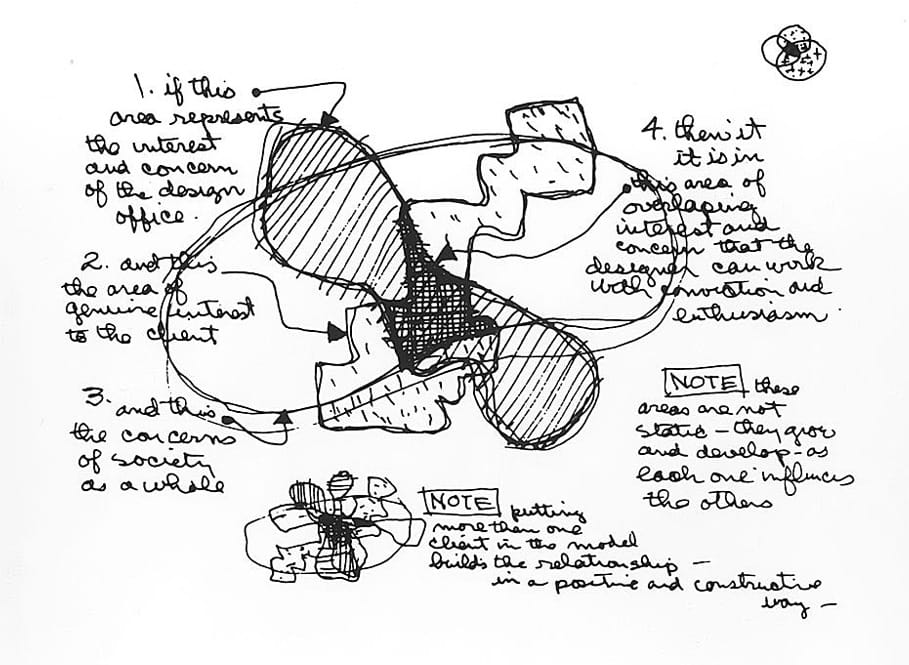

Design has so much more potential if we understand it as a methodology for making something out of nothing. If we acknowledge that it goes beyond a service. It’s a way of thinking that can bring entirely new companies, projects, and concepts to life. This is not to say that design has it all. But design is a powerful force when paired with partners who understand how to operationalize, market, fabricate, distribute, and do whatever else needs to happen for a particular concept to become tangible and thrive.

There’s a perception that “design thinking” disappeared in the early 2010s, after the initial hype wore off. But it may be more accurate to say the early hype within the design community was, in fact, the forum where interest waned. Global trends around the phrase continued; while expressed interest may have peaked, there is still strong global consideration of the idea.

Maybe it’s because, in this time of increasing uncertainty, we need more navigation tools to help us mark out more hopeful futures.

🤣 Ricky Gervais is a Designer

💡 Why Designers Must put Invention First