Ive got no Idea

Jony Ive and Sam Altman are betting we haven't hit the limit for how much tech we'll accept into our lives.

The big news in the design world last week was the marriage of ex-Apple design guru Jony Ive to current OpenAI guru Sam Altman. Ive sold his fifty-five-person hardware startup for a massive $6.5 billion. Considering that amount of money would keep a modest design office like Frontier in business for about four thousand years, it’s hard not to take notice.

The news was interesting to me for two reasons.

The first is the rare acknowledgement of the value of design within the tech community. Most founders still see design as an add-on when you’re ready to spend money on it, or something that has more to do with marketing than with product. This view is based on a limited understanding of what design methodology can deliver. If you’ve followed this newsletter recently you’ll know that I advocate that design is more than just what something looks like, it’s also how it works. And you’ll know that it can go even deeper. If we accept the etymology of the word design as meaning to “mark out,” and if we take that line of thinking far enough, then design is about setting a path toward what the future could be.

To do that, we can design narratives that connect our efforts into a rational and inspiring roadmap to that future. Not only is it about clarity of purpose and direction, it’s about bringing people in by offering a magnetic vision for the future.

In the case of Sam and Jony, there’s a clear understanding that design will help shape the future of how we physically interact with AI.

The next reason the news is interesting for me is the implications of the first reason. If Jony Ive is getting involved in such a profound way with OpenAI, it’s obvious that they see a platform shift ahead. In the world of technology we’ve shifted platforms once, significantly, over the last twenty years: from computers to smartphones. The implication of the Ive move is that all the ingredients are in place for the next shift. How can it fail?

Well, there are a few reasons.

I’m sure Ive and Altman have thought of the first. As far back as 2013, several players got into the wearables game. The most conspicuous was likely Google Glass. It felt inevitable. We were told it was just a matter of getting used to. The benefits were too great and would surely outweigh the negatives. After selling “only” one hundred fifty thousand units, Google pulled the plug and pivoted to an enterprise edition that focused on industrial and medical uses. Why did it fail? Among other reasons, it turns out people don’t like knowing they’re being watched. The simple human experience of speaking with someone wearing a pair of glasses that are recording them is … kind of a turn-off. Recent iterations of wearable glasses show more promise. Meta’s work with Ray-Ban has begun to address these issues, but it’s still a challenge that many, including Apple, are working through.

So that example of society saying “enough” in the face of seeming inevitable progress is obvious. But there are other examples where things ground to a halt (or were slowed) by some simple, visceral, and often irrational human resistance. In the mid-twentieth century, nuclear power was seen as the future of energy. The perception was that it was clean, efficient, and nearly limitless. The Chernobyl and Fukushima disasters changed that perception forever, despite the hard evidence that, compared with other forms of energy, nuclear remains one of our best and safest options on the path toward a more renewable future.

Another controversial technology that came to a grinding halt despite countervailing scientific evidence is GMO cultivation in Europe. As of 2024, there is one GMO crop approved for cultivation in the EU. By contrast, in the US, there are over seventy-million hectares under GMO cultivation annually. From a scientific perspective, the European Food Safety Authority has consistently ruled that approved GMOs are safe for human and animal health and the environment. And in this era of devastating impacts on farming resulting from climate change, GMO crops that meet safety standards provide relief for sub-Saharan African, South Asian, and some Latin American countries where drought-tolerant crops are genetically engineered to maintain yields with less water. But political and public resistance remains strong.

In both cases, it’s not that the resistance is unfounded. While there is no credible scientific proof that approved and safely developed GMOs are inherently dangerous to human health or the environment, there are concerns like an increase in monocultures that reduce biodiversity and increase systemic risk. What’s important, however, is that the technology triggered a basic human instinct to the point of meaningful societal resistance.

What’s odd in the case of AI and hardware is that public resistance to our deepening relationship with technology has not yet reached a point of outright cultural rejection. What OpenAI is banking on is that people will want AI to be more seamlessly integrated into their lives.

As of early 2025, it’s estimated that 4.69 billion people worldwide own a smartphone. If you take out kids aged 0–8, that’s 70 percent of the world’s population. That’s a pretty big market for whatever Ive and Altman are cooking up. But what if the trend line for tech adoption is not ever-upward?

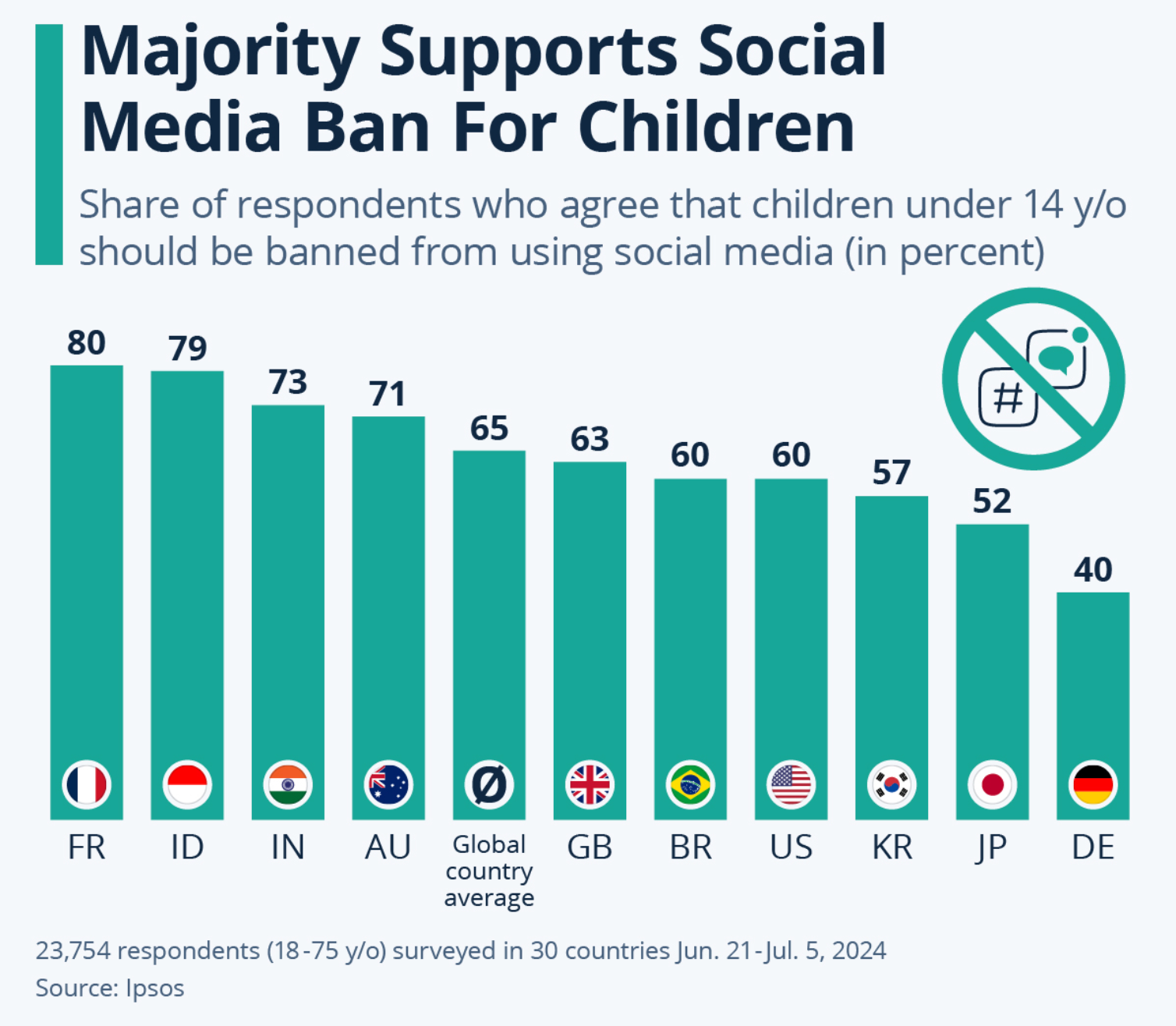

Australia has enacted a law banning social media access for people under age sixteen. If platforms do not comply, they receive a $50 million fine. In 2023, France mandated parental consent for social media use by kids under age fifteen. Spain raised the minimum age for social media accounts to sixteen and supports initiatives like “Mobile-free Adolescence.”

The list goes on to include other countries taking part in a growing movement that recognizes the negative impacts of technology on children. On that list of negative impacts are things like delayed cognitive development, increased suicide risk, reduced physical health, and other ugly outcomes of more tech use. As a result, the global market for parental control tools is expected to reach $3.39 billion by 2032. A big market, but still not as big as what OpenAI paid for Ive’s startup.

While there is a seeming inevitability in the ongoing infiltration of technology into every corner of our lives, there will come a natural point of societal resistance. An underlying issue is the additive nature of the technology itself for us grown-ups. Despite knowing that the average adult spends six hours and forty minutes on their phones every day, it doesn’t stop us. Despite knowing that that time amounts to about seventeen years of one’s life, we still don’t change.

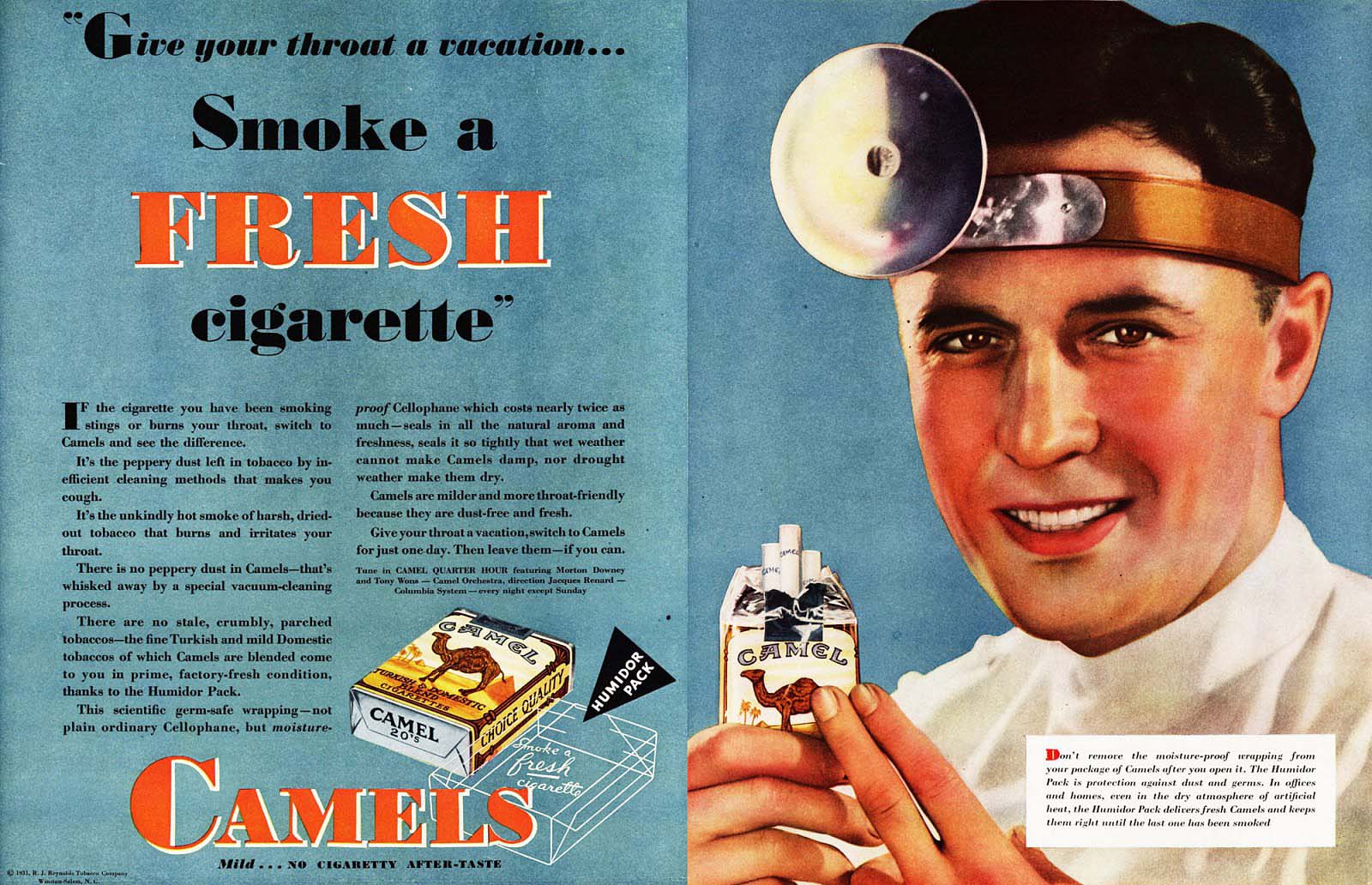

But change does happen. Society does eventually catch up. Tobacco was a dominant industry in the twentieth century. We’ve all heard how early marketing even suggested it was healthy to smoke. It took the better part of a century, but US adult smoking rates fell from 42 percent in 1965 to 12 percent in 2022. It took massive public-health campaigns, advertising bans, health warnings on packages, banning smoking in public places, and taxes and price increases for it to happen, but society and government did finally see the economic and societal cost of smoking and did something about it.

The fundamental assumption by OpenAI is that we’re on an inevitable path toward further integration with our technology. By pairing with the person who was in charge of design for Apple during the last step-change platform shift, OpenAI’s idea is that the trajectory started by the iPhone will continue unabated. That is a significant assumption. Moving from a handheld device to a different form factor that can leverage the promise and (sometimes disturbing) potential of AI as an overlay in our lives is one that has already been tried. It has yet to succeed because it rubs up against our human instincts in ways that are just too jarring.

What I’d like to see from OpenAI is deeper leadership. Rather than depend on continued addiction to technology and rather than exploiting the human brain’s neurochemistry for financial gain, I’d love them create a new story for the future. Better yet, I’d love to see the legions of kids growing up with technology build thoughtful and effective ways of shifting us past our helpless worship of technology.

There are people out there helping. Organizations like Half the Story, Screen Time Network, International Children’s Media Centre, and Enough Is Enough are all working at the grassroots level to help catalyze change.

A new story for our future would start with more than a hardware play. It would start with an informed engagement with everyone, literally. Artificial Intelligence marks a seismic global shift in humanity’s relationship with everything. That means shaping the future and writing the story of how we use it should include poets, farmers, teachers, bankers, architects, children, and anyone whose lives will be affected by it. That means everyone. And it should build toward a vision that society itself supports.

The opportunity for the next platform shift starts with understanding how the platform itself is no piece of addictive hardware but, rather, a productive, healthy, and generous experience of human life.