Art collector Ken Montague on Black joy and changing institutions from the inside

On representation, portraiture, the value of collaborating, and expanding his horizons

Ken Montague: I was determined as a collector to think about portraiture or Black portraiture in a new way that was going to be about, well, again, like my late father's phrase, “as we rise,” how we move forward. I really think that it’s possible, if you’re thoughtful about it, to establish a collection of portraiture that will be uplifting while being truthful to history and exploring ideas that I think are essential when we think about Black culture, Black identity, Black life.

Brian Sholis: I’m Brian Sholis, and this is the Frontier Magazine Podcast, where I interview artists, writers, technologists, architects, and other creative people about their work and the ideas and ideals that inspire it. Today I’m speaking with Dr. Kenneth Montague, an art collector in Toronto who has created both the Wedge Collection and the nonprofit Wedge Curatorial Projects. Founded in 1997, the Wedge Collection is now one of Canada’s largest privately owned contemporary art collections exploring African diasporic culture and contemporary Black life.

It’s also a private collection that is widely shared publicly, having been the subject of exhibitions at museums and galleries across North America. In this conversation, we talk about how Montague’s early life stoked his passion for art and culture, his belief in partnership and community building, focusing on expressions of Black joy, and working to change institutions from within.

You can learn more about Frontier Magazine and subscribe at magazine.frontier.is. Thanks for listening. And now, my conversation with Ken Montague.

BS: I’d like to begin by taking us briefly back to the 1990s, to the late 1990s, and begin in the hallway, so to speak. I wonder if you could just tell us the origin story of the Wedge Collection.

KM: I started to host Sunday afternoon salons in my wedge-shaped home gallery, which was basically the hallway of an old knitting factory in Toronto. A few of us got together and bought it as a sort of a cooperative. And I had this great space with seventeen-foot ceilings and, you know, a kind of a doorway that maybe you open up into a hallway that started at five feet and kind of expanded out to about fifteen feet in a triangular shape. So, right from the start the interior designer Del Terrelonge was calling the space the Wedge Space and I decided to showcase some art that I love, to bring it to Toronto for the first time, and called it the Wedge Gallery.

When things really got busy and the project started to take off and we’d have two or three hundred people, you know, packing into a loft on a Sunday afternoon, it got to be time to move on and started to become more nomadic. But the name stuck because it really is a bit of a double entendre. It’s also about wedging these artists and their practices into the story of contemporary art. So you know, it’s a name that really ended up being quite apropos and sort of emblematic of what I’ve been trying to do as a collector and trying to achieve through my non-profit, Wedge Curatorial Projects.

BS: I didn’t come across those efforts until they had already moved on to other venues. I moved to Canada in 2016, and I think the first exhibition that I heard about involving your collection was “Position As Desired,” which was at the Art Gallery of Windsor, which was itself a version of an earlier project that had toured elsewhere. But two things about it that were interesting to me is that it was one that you curated yourself, and then also Windsor is your hometown. What was it like to present your own take on your collection in your hometown a decade after you’d started, as you say, bringing things to Toronto.

KM: It was a pretty wonderful experience. Growing up the son of immigrants from Jamaica, we were kind of like an island in Windsor. To this day, I think we’re the only Black family in our middle-class neighborhood. So it was a big deal to be asked to go back and present a show with work from your collection.

It’s one of those, you know, Sally Field, “You really like me!” moments, so I was really happy to showcase work in a gallery that meant a lot to me growing up. I mean, it was in the mall, Devonshire Mall in Windsor was where, you know, the Art Gallery of Windsor was when I was a kid—which had its benefits. It was kind of a neat social experiment to have a gallery in a setting like that. But it had moved since and had a beautiful building on its own on the waterfront facing Detroit. So it’s this really great setting that celebrates the international border. And there’s a lot of interplay with American artists as well. And so I thought it was probably a very appropriate thing to have a show featuring work from my collection, which is very pan-African, it’s very diasporic. I live in Toronto and I’m very stimulated and moved by so many of the amazing and dynamic Black Canadian art practices right here. But then, the story goes beyond that and I’m very interested in how the local relates to the global.

So Windsor was a great place, not just because it was my hometown, but because it’s this border town. So much of my experience growing up was influenced by American culture. It was quite a positive experience to go there now, to see how Windsor had changed. It was now a city of immigrants and a lot of folks from the Middle East, and it’s just become a much more international place. And I’m showing work that represents, you know, contemporary African art from around the world. Altogether, a great experience. My late father got to attend that opening and I brought him up from the crowd. And that was a quite proud and wonderful moment.

My mother and father were big into art. We went to ball games, but we also went to Detroit Institute of Arts all the time. We went to the Art Gallery of Windsor. So it was really that early influence. I think seeing an image by James Van Der Zee of a couple in raccoon coats, which is now in my collection, seeing that on the walls of the DIA as a ten-year-old was a real reset to the kind of negative stereotype images I was seeing of African-Americans. I wanted to learn more about my own community in little provincial Windsor. So, you know, the whole thing of coming back to DIA, coming back to the Art Gallery of Windsor, where I spent many hours as a kid enjoying art, [was] a super enriching experience.

BS: In another recent interview, you had sort of described your time in Windsor as partly requiring you to make a world for yourself. And I had sort of assumed that was related to the fact that, as you say, yours was the only Black family on your block or in your neighborhood. But in fact, it’s already cross-border, cross-cultural. It’s a kind of polyglot, polyvocal cultural experience that your parents and your family helped you to

encounter for the first time and enable you to then keep building, keep making these worlds for yourself.

KM: It’s so true, Brian. It’s a good observation. And beyond that, I have to also add that around the house there was this very rich Caribbean culture: the food, the music. Just a really great tricultural experience—American, Canadian, and Caribbean. So all of those things are tropes and elements in my Wedge Collection now. And you can really see the source.

BS: Perhaps the largest endeavor that the Wedge Collection has done to date is As We Rise, which is a book that’s published by Aperture and also a traveling exhibition of over 100 artworks. I think the title also has a personal meaning for you, if I’ve read correctly, and it connects to your thoughts on community-building. How did As We Rise come to be?

KM: I’m very close with the people at the Aperture Foundation in New York. Always respected them as sort of advocates for photography, and they’ve always been a very diverse and forward-minded organization. So, you know, I look in my library and I see books on Diane Arbus and, you know, all the way to Hank Willis Thomas and … oh, you look at the spine, it’s always Aperture. So it was always my favorite photobook publisher. It was a big honor for them to ask me to submit an idea for a book. They had visited my home and seen some of the collection on the walls. I think that was the seed that was planted and Chris [Boot, then the executive director] later asked me to consider submitting a project for a book.

BS: As We Rise has an outside curator, and you have increasingly turned to others and invited them to make their own selections, their own interpretations, of the artworks that are in the Wedge Collection. Tell me a little bit about that decision, and then also about what you’ve learned from having outsiders go through and think about and work with material that has been so personally meaningful and important to you.

A show cannot evolve without that curatorial voice, that outside voice. It’s a way of working that has enriched my collection.

KM: I’ll actually start from the title, As We Rise, which was decided by committee. I think the people at Aperture—the book editor, the curator of the subsequent show—they were thinking a lot about my origin story and something that my father had always said to our family. It was kind of a family motto, this idea of “lifting as we rise.” So you pull up others as you do well. And I think that the people at Aperture thought that was a great metaphor for how I’ve been approaching collecting. That kind of decision-making—you know, by committee—that kind of collaboration has always been the way that I work. I’ve found that it's a much more enriching and engaging experience for the audience, for the reader to, you know, have others who may have, you know, different viewpoints.

It’s actually most exemplified in the show that's currently at MOCA in Toronto, Dancing in the Light, where the two curators, Kate Wong and Farida Abu Bakare, visited my home independently, saw how much I enjoy living with music and with books, and decided to make that a prime feature of their subsequent show. So, you know, they designed a beautiful vessel that contains some of my favorite books. And my actual albums. It really gives you a bigger and more intimate sense of how I collect.

I would have never thought to do that on my own. I think that you bring in an outside force and it can only enrich the experience of a collection. It’s just the way that I work. And I think that there’s nothing wrong with doing things on your own. I’ve had great experiences, you know, organizing a show like Position as Desired. I’ve just learned that a show really cannot evolve without that curatorial voice, that outside voice that’s shaping it as it moves along. It’s been a way of working that I think has only enriched my collection.

BS: At the beginning of that answer, you said that As We Rise was an appropriate title also for how you approach collecting. And this notion of working with outside curators and learning from the work that they do independently from you and bringing those ways of working together, maybe defines something about how you approach collecting. So can you tell us a little bit about what you do differently now in 2023, based on all these experiences you’ve had with different curators and other outside experts, versus the way you were collecting fifteen years ago when you were earlier in your journey.

KM: I think that the outside influences and some of the decisions that have been made by curators who I’ve worked with have broadened my vision as a collector. I started out exclusive to photography. I still love photography, but it was my way into the world of contemporary art.

Being a non-academic, I think photography was really the art of my era. You know, I kind of came up in the 1980s, really. And that was where things were at: ’70s, ’80s, identity art, artists like Lorna Simpson and, here in Canada, Busseji Bailey and David Zapparoli and others that had a very, very clear vision that I completely understood as a second-generation Black Canadian. But there were many other stories to be told and it actually broadened my collecting habits and the artists that I was interested in to realize, through these external voices, learning from curators actually, that there’s a whole world out there in terms of varied media.

I was really focused on straight portraiture when I started, and realized you can tell similar and expanded stories through various means, like conceptual art. So that started to become something interesting for me. It broadens out, you know, it’s like a slowly opening flower. The petals are sort of moving out and then you see all the different grooves and lines in it, and it’s like many different paths to sort of get to where one’s going. So for me, the move to painting and video art, sculpture, you know, all sort of showcased in this current show at MOCA, happened in an organic way.

BS: I think that Dancing in the Light, the show that’s now on view at the Museum of Contemporary Art here in Toronto, is perhaps the first, at least that I’ve known, large public instantiation of that broadening, of that new depth. And it includes work in many different mediums, and instead of it being sort of medium-specific—photographs from the Wedge Collection—it is instead a genre show. And I think it’s important that Kate and Farida chose portraiture. And I think also with the inclusion of books and records in some ways, the show then doubles as a self-portrait. Once again, it’s in your hometown. Can you talk a little bit about portraiture and what it means to you?

KM: I think it all comes back to that origin story, that feeling of being not a part of things and wanting to be a part of things as a child. I think for me, it’s a real reflection of self. You know, you’re looking at that photograph of a person and there’s the gaze, they’re staring back at you, there’s a dialogue between the viewer and the subject. But then you move to thinking about the dialogue between the subject and the photographer.

I realized along the way that I had been collecting work at the beginning in photography where the subject had no control over how they were being depicted. I have a lot of work that’s, you know, early photography from the Caribbean, much like work that’s in the Montgomery Collection at the AGO in Toronto. Those works, looking at indentured laborers on a cane field, are really important images to have in the collection. We need to explore those histories and think about where we’ve come from.

But also I realized very quickly that for me, the idea was to think about uplift and think about Black joy and not focus on oppression and on, you know, the pain. So many of those images exist already out in the world. And I was determined as a collector to think about portraiture or Black portraiture in a new way that was going to be about, well, again, like my late father's phrase, “as we rise,” how we move forward. It’s not relentlessly upbeat. You can still think about tropes like community, identity, and power. It’s still inclusive as a collection of images that think about protest, that think about the difficult times that people went through overcoming oppression.

I really think that it’s possible, if you’re thoughtful about it, to establish a collection of portraiture that will be uplifting while being truthful to history and exploring ideas that I think are essential when we think about Black culture, Black identity, Black life.

BS: Would you say that now in the 2020s, you have found after fifteen or twenty years of doing this work, a cohort of other figures with whom you feel an affinity, that they too are focusing on, as you say, Black joy, focusing on uplifting versions of the Black experience? Where have you found—if anywhere, I don’t want to presume—a sense of community among other collectors, other institutions, other curators?

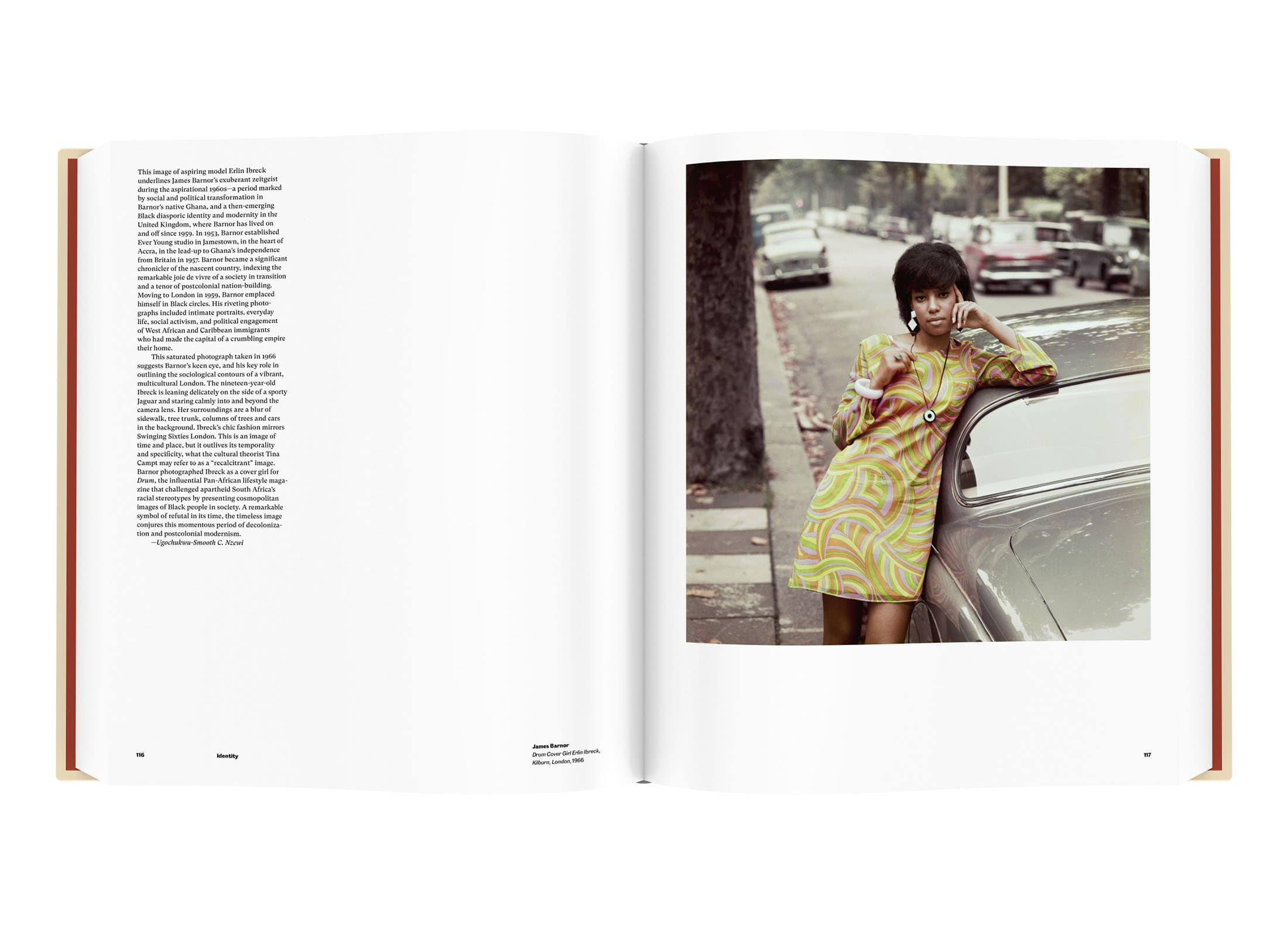

KM: There were always a few of us in the trenches thinking about Black Joy. As I evolved as a collector, I started to meet some very like-minded individuals, not always collectors. I have to say, it really has been curators who have been my colleagues in this struggle to bring Black joy to the forefront. Early on I met Okwui Enwezor, who was an incredible researcher and he would just let the image do the talking, you know. He was a beautiful writer but much of his curatorial practice was just, you know, more is more, showing us there was all of this beauty and ordinary Black life, say, happening in mid-century West African societies that were going through moments of oppression but kind of breaking through and becoming independent. How people presented themselves, what they wore, the props that they would bring to a studio, the way the photographer—who was part of that community—would want to dress those folks and capture their images for posterity.

That kind of celebration of Black joy really, really spoke to me and informed my early collecting. But it wasn’t so celebrated, you know, as a mainstream kind of movement in contemporary art the way it is today. It actually took a long time. In fact, it was brewing underneath, and other curators in the field—you know, Thelma Golden, Bisi Silva, others who I met and became friendly with—were exploring these ideas in their curatorial projects.

But it really wasn’t actually until the moment of George Floyd, not so long ago, that institutions finally said, “Okay, we’re not just going to go with these same five names, with black artists that we have in our collection.” It was like there’s a whole world out there of folks who are exploring, as I call it, the beauty of ordinary Black life. And then this collection that I put together was suddenly being celebrated in a much larger way.

For me, nothing had really changed about the way that I collected. It’s just that the world came around to it. It’s something that I believed in from the start, this idea of uplift and thinking about how we gained as a community by being supportive of each other, how we move forward with joy being a place to get to—this idea of relaxation and leisure time, you know, showing images like that. And now we have a whole cohort of young photographers that Antwuan Sargent calls a new black vanguard that are even changing fashion photography and thinking about, again, this beauty of ordinary life.

It’s a different way of thinking that I think has now infiltrated the mainstream. But it is something that I've been doing for over twenty-five years as a collector. It’s just, it’s who I am, you know?

BS: And I’m sure that’s incredibly gratifying. And I think that one adjective I’d also like to throw onto the pile of adjectives here is enthusiasm. In my encounters with you in Toronto’s art community and elsewhere, I have seen that enthusiasm and a kind of supportive attitude is a default stance for you. And I think that’s also what allows you to sort of pull together and build a community and to have curators at your side, writing with you and doing this kind of work together.

If I had to kind of characterize how, in the basest terms, how things have changed for you from the beginning to now is that at the beginning you had a space but not a nonprofit. And now you have a nonprofit, but not a space. And one of the things that I think is interesting is that you are committed to institutions. You’ve mentioned Aperture, you’ve mentioned the Art Gallery of Windsor, you’ve mentioned MOCA, you’ve mentioned the ROM. These are all places that have their own physical spaces, have their own needs, and you’ve been generous in sharing what you have amassed as a private collection. Can you talk a little bit about that stance and why you’ve chosen that as opposed to the Eli Broad or the Glenstone Museum [approach], the “I’m going to build my own temple to the culture that I want to celebrate.”

KM: Well, some of it is resources, but also I really think you gain by being collaborative with these kinds of situations. I think that there’s a danger in building your own temple, even though you have creative control, that can sometimes turn on itself and you know, you're presenting something that becomes so highly subjective as to be exclusive. And that’s exactly what I’m against. I’m all about the inclusivity and sharing experience. And, you know, the kinds of relationships that I build with institutions, you know, I’m on the board at the AGO in Toronto, and that’s a good example, being able to be influential in bringing people from my own community into the fold, people that maybe didn’t know that the place would be welcoming for them. People that didn’t have positive experiences growing up going to a place like the ROM or the AGO because they weren’t seeing reflections of themselves on the wall. You know, being on the inside as a trustee, you know, does give you the opportunity to work on changing the game.

The idea is to make sure that these institutions reflect the communities that they serve on all fronts.

In the case of the AGO, you know, I worked very closely with Julie Crooks about enlisting people in our own Black and Caribbean communities here in Toronto in purchasing works from the Montgomery Collection that ended up being a very signature event. This is the first time that a major purchase was done for the AGO where it was one community coming together and kind of saying, “We’re gonna buy this for ourselves and for our families and for our children.” And of course, the great thing is that those folks then become part of the community of the AGO.

So I’m really trying to make change from the inside, not an easy thing to do all the time, but I’m in a unique position to do that. Again, never an easy thing. Sometimes you can’t do it, but you have to try. You have to bring others in. The idea is to make sure that these institutions reflect the communities that they serve on all fronts—you know, from education to programming and the choice of exhibitions. That’s a personal mission.

But the other mission is around the idea that we just need more Black collectors. You know, I go to Art Basel Miami [Beach], as I will in a couple of weeks, and for many years, using that place as an example, I was the only person in the room that was Black and I would go to parties and events, I would go to, you know, a gallery’s dinner, and it would just be myself, you know. I would never meet other Black collectors. And that’s changing. And that’s a thrill for me. I’m very involved in the Black Trustees Alliance, which is a new organization that’s trying to network and branch out to find other Black folks that are committed to institutional change and are collecting on their own. So that’s kind of the current mission now, not to give up the work that’s come behind it, but I’m now in a unique position to sort of try to be influential about how we see art and how we consume it in our institutions.

BS: I’ll just briefly go back to the Montgomery Collection that you mentioned, because the work that you and Julie and so many others did to bring that collection into the museum—it resonated immediately. Both for what those photographs are, what those objects are, and the societies and cultures and people they represent, but also when the press release was sent out, there were probably thirty or more names attached to who was responsible for funding that acquisition. I can picture a future in which one photograph from that collection is on the wall in a permanent collection gallery, and the label has to be twice as long as all the others, because it’s not just the name of the president of the board of the trustees, it’s all the people that worked as a community to bring it together. So it’s not just about representation, it’s about another way of thinking about how an institution can be supported, and democratizing how an institution can build its collection.

KM: Yes, it’s true. I think about Barack Obama and it was like not about getting 500 million-dollar grants from organizations. It was about, you know, “Let’s get all the folks in my community to give $5 to this campaign.” It’s something that is very infectious. It’s the way to go, although it is a long play. It’s not a quick thing. It’s about a lot of energy spent educating and bringing people into the fold. But I think people very naturally and automatically jump into something when they see the benefits, so it’s up to me and my colleagues to explain that benefit. What do you get out of giving to a place that you’ve never thought about giving to before? What’s in it for you? And there’s a lot, and I think that as we move forward, institutions must change. They will change or they’re gonna die, and the change is gonna be about bringing in those other voices in terms of curatorial, in terms of who is running and managing the place, and bringing in those other voices in terms of, you know, the communities that had previously felt excluded.

Thanks for listening to this episode of the Frontier Magazine podcast. It’s the audio component of our weekly publication, which features appreciations from the forefronts of architecture, technology, culture, and education. Each issue shares new ideas about how design and creativity accelerate positive change. Everything we publish is available for free; browse the archive and sign up for new issues at magazine.frontier.is. If you liked this episode, please share it with people you know and rate us to help others discover what we’re doing.

The magazine and podcast are products of Frontier, a design office in Toronto. Here’s studio founder Paddy Harrington:

Frontier is a design office. We believe in the expansive potential of storytelling to help people navigate the unknown to get somewhere new. We’re coming up on a decade of designing big stories in the form of strategies, brand identities, editorial products, and digital and real-world experiences that help organizations, brands, and individuals stand out and discover new creative territory. Learn more at frontier.is.

Thanks again. I hope you’ll join us for the next episode.