Making Change

Two creators show us it doesn’t have to be this way

Hi everyone,

This week, two inspiring stories from distinct creative worlds. One, on Yasmeen Lari, Pakistan’s first female architect, is about overdue recognition of both pioneering designs and an outlook that has come into increasing global relevance. The other, about fashion designer Telfar Clemens, is about someone young using newfound power to buck industry convention. Both remind me that every tradition is just an accumulation of practices and habits, and that, whether young or old, we can rewrite the stories we tell about how things are supposed to work. Pairing these stories with the first hints of spring weather in Toronto has me feeling invigorated. I hope the same is true wherever this finds you.

Love all ways,

Brian

Challenging Conditions

“The way we practiced architecture in the last century is no longer relevant,” says octogenarian Pakistani architect Yasmeen Lari in a recent interview. I no longer remember when I first came across the pioneering architect’s work, but I know it was after 2005, when she responded to the major earthquakes in Kashmir by designing zero-carbon relief shelters that affected community members could build themselves.

That encounter was fleeting—Lari certainly did not receive as much press for her humanitarian work as had Japanese architect Shigeru Ban, whose paper log houses, designed in the wake of the 1995 earthquakes in Kobe, Japan, were widely celebrated and have been regularly produced elsewhere. (And please don’t get me started on the fawning over the well-intentioned but poorly conceived Brad Pitt–sponsored architecture projects in post-Katrina New Orleans.) In the more than a decade I’ve been waiting for a major English-language consideration of Lari’s career, she has focused almost exclusively on humanitarian work. This is partly because Pakistan, she has noted repeatedly, is one of the countries most affected by climate change. “I know the damage it causes to people’s lives,” she says in that same interview.

Now the Architekturzentrum Wien has produced the first in-depth survey of her five decades practicing architecture, arranged around the idea of building “for the future.” From creating modernist icons for a country emerging from the shadow of colonization in the 1970s and ’80s to her recent efforts to revive local building traditions and encourage decarbonization, the Lari that emerges is formidable. She grapples with how to create the conditions for stability, identity, and community, at the local and the national level and during times of political and environmental flux, through the built environment.

The accompanying catalogue (MIT Press; buy at Bookshop or Indigo), with its hundreds of photographs, eleven commissioned essays, and lengthy interview with Lari, is an indispensable resource not only for those interested in her work but also those who want to build in an increasingly precarious world. Among its stories are the design for nearly eight hundred units of social housing built in Lahore in the mid-70s; the enormous Finance and Trade Center in Karachi, which brought together more than ten state-related enterprises during the ‘80s; and her preservation work, including two UNESCO World Heritage sites. Throughout, she takes special care to accommodate women, children, and other vulnerable peoples and to work with, not against, environmental conditions.

“We need to rethink everything and we have to do it now,” says Architekturzentrum Wien director Angelika Fritz, who co-curated the exhibition. “That is the challenge that architect Yasmeen Lari gives us.” While there is much to admire about Lari’s designs, her process and approach resonated most as I read this dense and engaging volume. Throughout, the emphasis is on Lari’s willingness to learn, collaborate, and teach. She was rethinking (or, as she puts it at one point, “relearning”) all this time. That example, more than any specific building or initiative, is the strongest challenge, and the greatest inspiration, the rest of us can hope for.

Adjusted for Inflation

By the time writer Emily Witt profiled fashion designer Telfar Clemens in spring 2020, he had won the CFDA/Vogue Fashion Fund award, dressed celebrities for the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s annual gala, and presented runway shows in Paris and Milan. But he had also collaborated with The Gap and designed uniforms for White Castle employees. At the end of the piece, Clemens returns to New York after a months-long whirlwind in Europe. As Witt observes, at that point “he was not motivated to make the kind of fashion that served a small class of out-of-towners, and he contemplated how he might sell his clothes in a different way when he was in New York.”

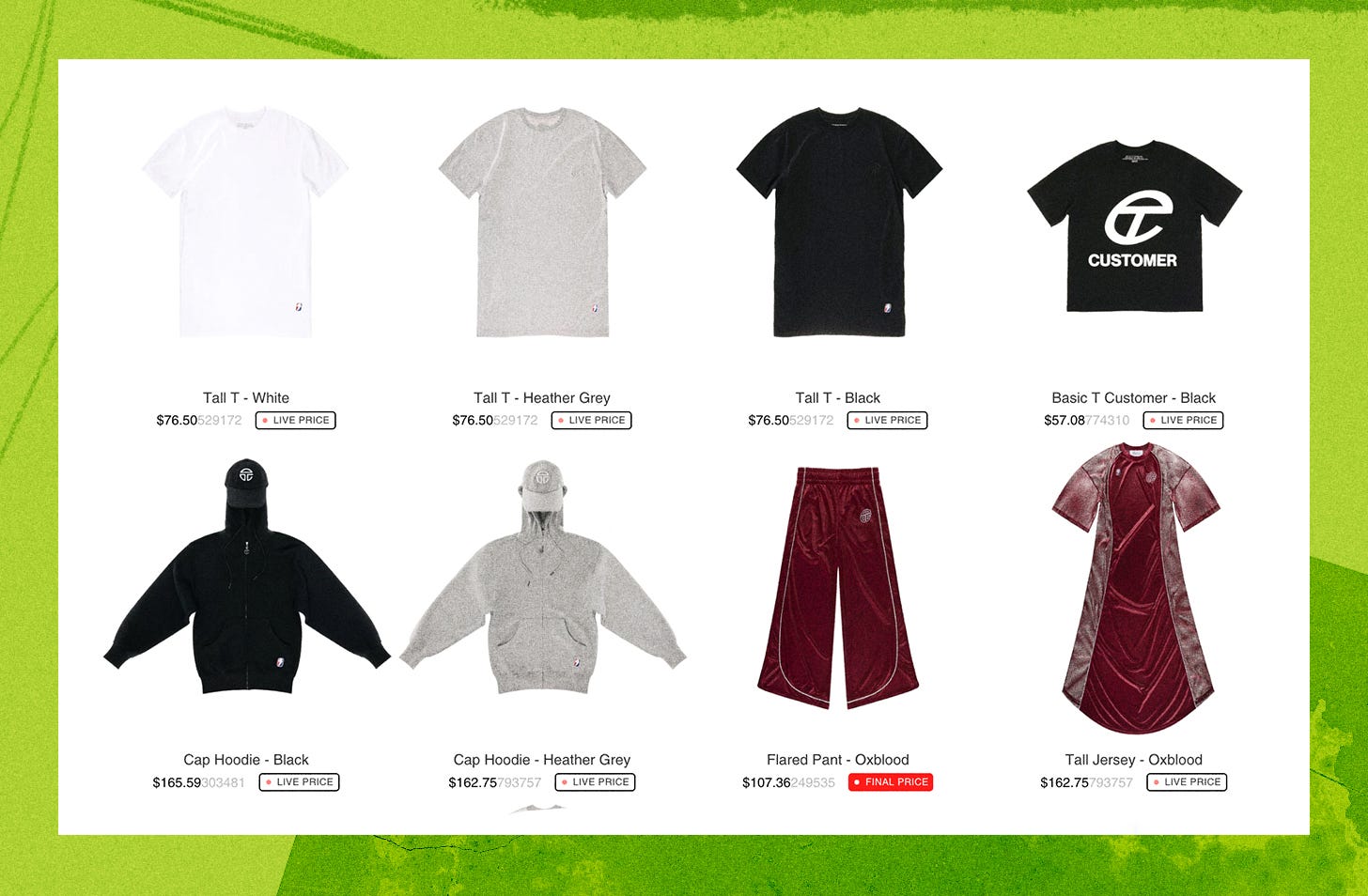

Telfar Live, which launched on Monday, is to date the most significant outcome of that line of thinking. The idea’s radical approach stems in part from its simplicity: the most popular, fastest-selling items should be the cheapest. On the Telfar website, new designs are launched at their wholesale price. As the seconds tick by, the cost increases incrementally toward the retail price—something you can watch in real time as you contemplate your choice, select your size, and click “add to cart.”

The fine print on product pages cheekily acknowledges how this upends fashion-industry norms: “WARNING: TELFAR LIVE is a total reversal of the markdown sale structure of the fashion industry: TELFAR LIVE is literally a sale in reverse. Using TELFAR LIVE may disrupt both preconceived notions of value & scarcity and supply & demand. If you are having symptoms of clout chasing, elite capture, OR ENJOY GETTING GENTRIFIED OUT OF YOUR OWN CULTURE—CONSULT YOUR ANCESTORS TO FIND OUT IF TELFAR LIVE IS RIGHT FOR YOU.”

As of this writing, nineteen of the twenty-nine items released on Monday are sold out, all for around a quarter of the stated retail price. (The most expensive of these items, a gown-length basketball jersey with mesh sleeves, is $164.04.) This is partly about unit economics: with sales guaranteed, Telfar can place a larger order with the factory producing the items, then pass on the savings to customers; at the same time, like Costco, the company can profit from slimmer margins because it is selling more units. It’s also about waste: on Monday and Tuesday, fans guaranteed that, for those nineteen designs at least, everything Telfar ordered from the factory would find a home. No pieces would begin the long journey from high-end boutiques to discount stores to outlet malls to textile dumps.

I’ll be watching with interest to see whether these designs end up on resale sites and, if they do, for how much. I’m also curious whether other labels follow in the company’s footsteps. If asked, would Clemens and his team share the web code for its dynamic-pricing shop? But for a company whose slogan is “Not For You, for Everyone,” at this early point Telfar Live seems like a rousing success. Here’s to further experimentation.

Curious to know more? Watch the gleefully zany minute-long video announcing Telfar Live; listen to Clemens and artistic director Babak Radboy on the How I Built This podcast; read Ana Andjelic, writing in 2020, on Telfar’s “reverse pyramid”; or read Witt’s long and engaging New Yorker profile referenced up top.

🔗 Good links

- 🌨️ Film critic Amy Taubin on Michael Snow’s canonical 1967 film Wavelength

- 🎙️ A wonderful podcast interview with the writer Hilton Als, on Prince, profile writing, growing up in Brooklyn, Joan Didion, and his writing routines

- 🗣️ “In its ideal form, it involves no audience or judge, just partners; no fixed agenda or goals, just process.” Hua Hsu on conversation.

- 🌩️ “Nearly every person in it looks as if they are about to be struck by lightning.” Critic Dwight Garner on the radicalism and legacy of Wisconsin Death Trip