Neighborhood Watch

Let people become mayors of the medians and presidents of the empty plots

Hi everyone,

This week, some notes on the neglected spaces in our cities. Some people have the neighborly impulse to care for overlooked plots, the interstitial spaces that don’t merit bureaucratic attention, and they should be secure in the knowledge their good work won’t be undone. That story after this week’s good links.

I went to the Shein website for the first time in my life and learned that a DAZY Solid Ribbed Knit Sweater is the price of one month’s subscription to Frontier Magazine. Wouldn’t you rather have 4–5 essays and interviews about the built environment, plus links to two dozen or more great stories, than something you’ll wear once and forget at the back of your closet? Click “view in browser” then one of the subscribe buttons. The buttons are green so you can also say you’re doing it for “brat” summer.

Until next week,

Brian

🔗️ Good links

- 🏢👀 Buildings that caught my eye: Rijnstraat 8, retiring OMA partner Ellen van Loon’s 2017 renovation of a Dutch government office; Konishi Gaffney’s renovation of a Edinburgh garage into an artist’s studio; Bétillon & Freyermuth’s straw-insulated Toulouse housing complex

- 🛝🚖 More on streets and autonomy: Stephanie H. Murray on “what adults lost when kids stopped playing in the street”

- ⛩️🇯🇵 Following up on my essay about Tokyo, here’s writer-photographer Craig Mod on sento public bath houses, Shinto shrines, and other places under threat by development

- 📝📐 Following up on last year’s essay on unionization in art institutions and architecture studio, the union at Bernheimer Architecture has ratified a collective bargaining agreement

- 🕰️♻️ FM podcast guest Deb Chachra asks “How might we apply the ethos of adaptive reuse to objects?”

Neighborhood Watch

For twenty-five years, Didier Courbot has made small, anonymous contributions to the street life of the cities he has lived in or passed through. The artist, who has exhibited photographs of himself performing these actions under the series title needs, has planted flowers on a sidewalk in Rome, installed a birdhouse on a lamppost in Paris, repaired a broken curb in Florence, and fixed and cleaned an abandoned bicycle in Osaka. As the critic Jörg Heiser wrote not long after Courbot began this work, “The artist turns into a tragi-comic, hopelessly romantic figure who confuses the anonymous urban space with his own garden, someone who hasn’t yet heard that Modern society doesn’t rest on a little bit of goodwill and a helping hand, but on the ever more complex division of labour.”

Courbot’s work, and the title of his series, came to mind as I read Australian landscape architect Alastair Kirkpatrick’s argument for altering urban streetscapes to better reflect what we think of as “landscapes.” As he notes, streets in most parts of the world facilitate vehicular traffic; drain water into sewers; and host the pipes and wires of our other infrastructure. Those needs operate at the level of the city and are generally best served by bureaucracy. Yet streets still can do more, can address qualitatively different needs, and should. “Probably the simplest way to convert a streetscape into what people might perceive as a valued landscape is to increase its vegetative mass and vegetative diversity—put simply, by digging up the grass and planting out the nature strip.” Doing so breaks up the monotony of our streets, with their equidistant, fenced-in trees and lampposts. But it also increases biodiversity, mitigates air pollution, and, importantly, gives people a sense of agency over the places where they live.

Unprogrammed spaces in the city—whether officially abandoned lots or the weird slivers another artist, Gordon Matta-Clark, termed “fake estates”—need not be unloved ones. People can and do step into the breach, planting flowers or whole gardens, creating parklets, and otherwise responding to the community’s needs that exist beneath the bureaucratic radar. But the work of caring for them undertaken by neighbors is precarious, as architecture critic Anjulie Rao noted in an essay I commissioned last year: “These plots provide beauty, nourishment, respite from intense summer heat, and spaces to play or socialize. Yet, they are not ‘owned’ by any one person or entity; they don’t generate profits. They sit squarely in between vacancy and speculative development.”

Rao was writing about Chicago. This stewardship happens around the world; in another interview I conducted last year, the Filipino artist Leeroy New described “guerrilla reclamations” in Manila like roadside vegetable gardens. “Stewardship initiatives are often valorized through news stories or community awards from nonprofits,” Rao writes. “Rarely does such recognition come with the means to make these spaces permanent, or even the capital to continue that stewardship.”

How can cities like Toronto accommodate these small-scale efforts to make our cities more livable, healthy, and just? At the least, they should strive to devolve authority over these sites to the people who live nearby and act as stewards. Want to spruce up the median on your residential street? Go ahead, so long as what you create does not infringe upon broader urban “needs” like infrastructure. Want to erect something longer-lasting on an empty lot? Create a system by which appeals can be made through local representatives like city councilors and formal agreements—essentially, free leases—can be crafted. Such a guarantee should transferable to someone else in the community but otherwise inviolable without negotiation that includes the stewards. This would encourage more significant, and likely more beneficial, interventions.

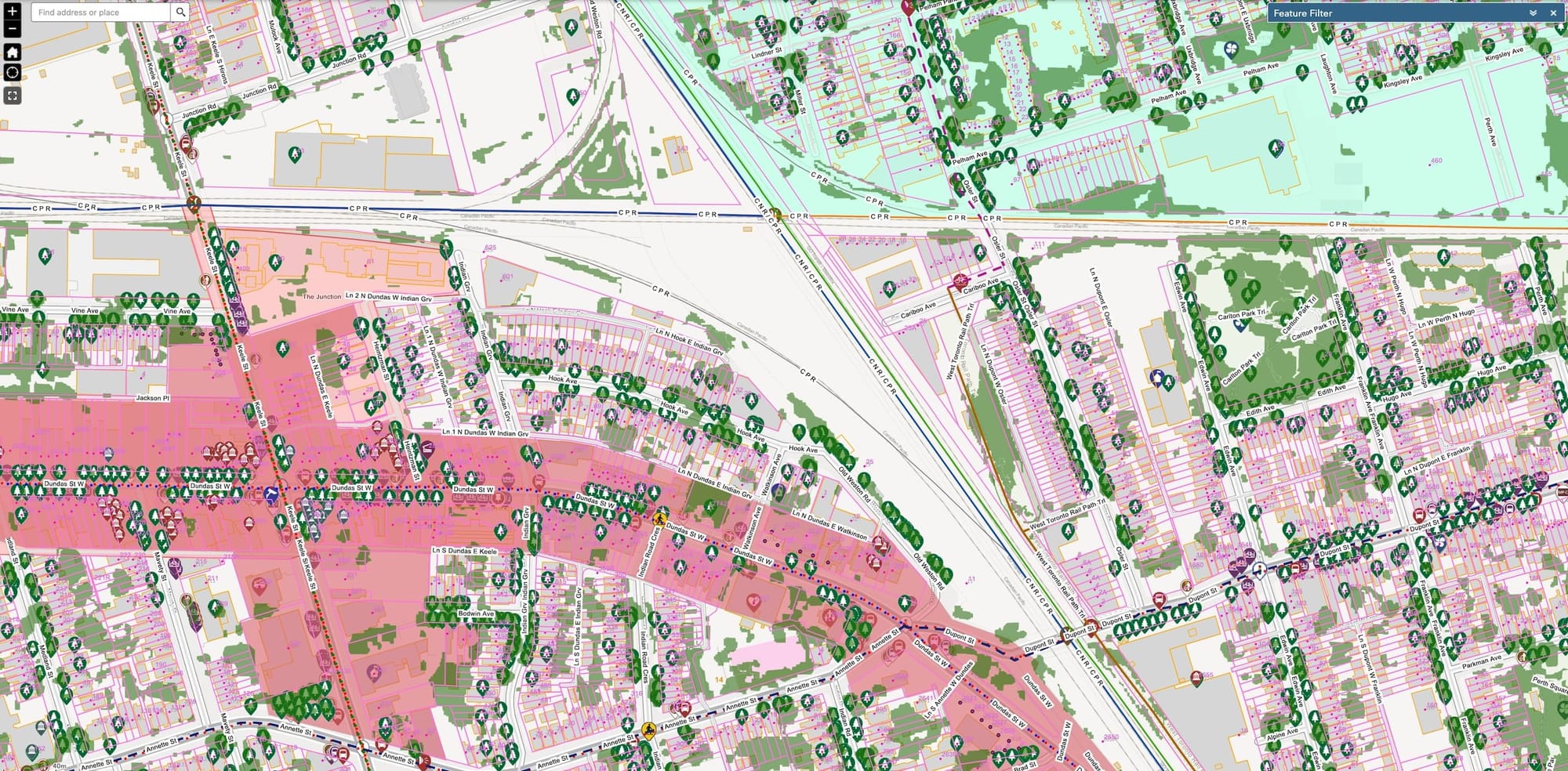

Above is an official City of Toronto map of my neighborhood overlaid with all the information available online: lot lines, business-improvement districts, tree coverage, and the like. After living here for seven years, I know of many interesting, well-used, even loved spaces that show up in the “untouched” light-gray zones. My neighbors already put them to use in provisional ways—after I finish this newsletter, I’ll take my dog to the unofficial dog run near one of those curving rail lines. Creating a system by which we can feel secure to make more intensive interventions would allow us to contribute even more to our quality of life—and, in small ways, to the life of the city as a whole. Rao again: “Equipping residents with tools and agency over land that has previously been devalued holds the potential to build solidarity networks between stewards; provide locals agency and control over land deemed invaluable; and, importantly, legitimize the ‘third way’ of developing fallow land into ‘productive’ spaces outside of conventional real-estate capital.”