Networking Opportunity

A networking service that gives users peace of mind and reinvigorates the original premise of the internet

“Let’s step back for a moment and ask what actually makes human culture work.” It’s not the first thing you’d expect to hear in conversation with a tech-startup founder, one who also says, “I’ve been studying computer networks and systems design for decades.” Yet it quickly becomes clear that Tailscale CEO Avery Pennarun sees analogies between computer networks and (offline) social networks, and is as fascinated by large questions as he is by technical details. The company he has founded offers what it calls a “zero-config VPN” that eliminates network-security concerns without requiring a complicated setup process.

Pennarun broadened the scope of our conversation in response to a query about how Tailscale attempts, as he has written elsewhere, “to fix the internet.” What are its problems? Most of us think first of the corrosive effects that social media can have on our politics. Pennarun’s company, however, is engaged one level deeper than Facebook and Twitter: “Below the web layer is the internet layer, and over the past two decades working on the internet layer has become much more complicated.” Tailscale product designer Ross Zurowski adds, “Because the internet’s default stance is open, not secured, you have to introduce tools and systems to make it more secure. Those tools and systems are where complexity—and mistakes—get introduced.”

How have we mitigated those problems to date? Pennarun continues by suggesting we’ve defaulted to letting large corporations, which can throw resources at a problem, solve them for us. “Google, Microsoft, and Amazon provide a lot of value and allow people to do amazing things. But this centralization has also done damage.”

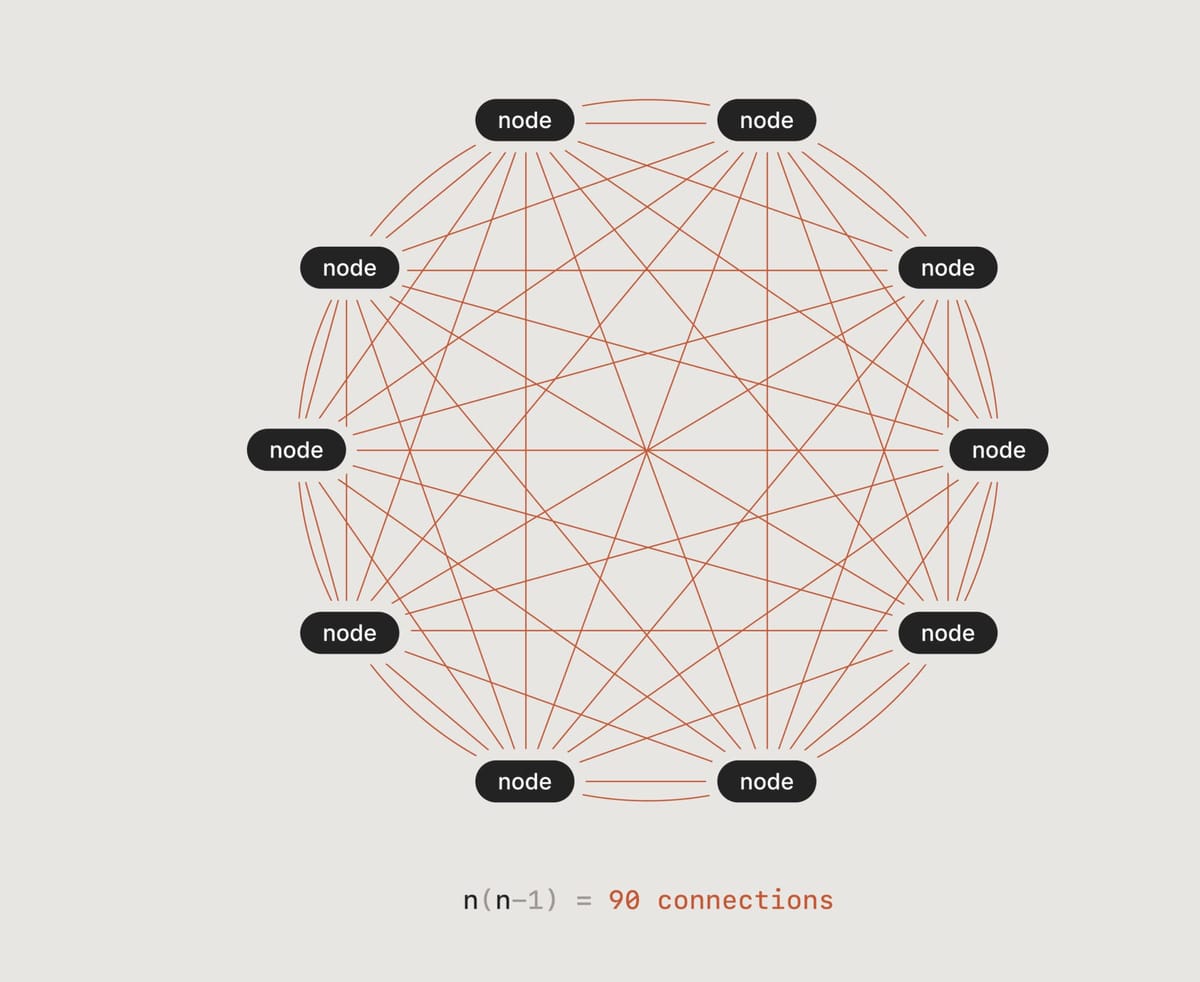

Zurowski describes Tailscale’s governing idea as a “judo flip”: “What if we changed a few small things to get rid of all these problems? For example, at a fundamental level, Tailscale ties an identity to every piece of information that goes over a network.” Tailscale networks are also “unknown to the outside world. By default, they can’t be seen or accessed via the Internet. That helps you avoid the thorniest problems: for example, the Equifax data breach happened, essentially, because a computer on its network was also connected to the internet and a hacker guessed the password.” That’s not possible with Tailscale, where a network’s administrator has granular control over who participates in the network and what kind of access they have. It’s better for users, too: once you’re a verified user of the network (a “Tailnet”), for example, you no longer need to log in to the network’s services. You simply connect and get to work.

How does this tie into human culture? Until the past fifteen years, Pennarun notes, “we’ve never had the problems that arise when people have instantaneous broadcast access to millions of people, or that arise when that communication can be instantly surveilled, panopticon-style. Humans did not evolve for this, but rather to interact and work in small groups. Those small groups can coordinate, but there is a structure to those associations. It’s not a free-for-all.” He adds: “The original design of the internet was for a network of networks. You would build your own small network, then connect it to others in a sensible way, and those interchanges could have controls. It was similar to the structures that characterize human social networking.”

Tailscale, as a proposition, suggests that Web 2.0—the era of massive, centralized platforms—has broken that original vision of the internet. And by allowing people and organizations to easily build small networks of computers they can trust, and then invite in people they know won’t be bad actors, they won’t have to be guarded in every network interaction. “I don’t have to be as careful because my friends [or coworkers] aren’t going to attack my server with malware,” as Pennarun describes it. “We solve tangible, concrete problems for developers and IT teams. But the functionality we provide is a carrier for the bigger commentary on how we believe humans should interact.”

Yet he’s quick to distinguish what Tailscale does from Web3 advocates of complete decentralization and blockchain-based accountability, who also have opinions about how humans should interact through technology. “Our model is a careful design based on all of the [networking] options out there. What resulted from that study is a hybrid centralized-decentralized architecture. Control over the network is centralized in one location, but the data that gets exchanged is decentralized.” The system’s peer-to-peer efficiencies make the service zippy and save its customers money. But they also avoid what he sees as a problem with many Web3 solutions, which “come from a place of religious zeal for decentralization. Just because the system is centralized doesn’t mean that decentralizing it solves our problems. The actual problems are not with centralization but with many other things.”

Whether Tailscale’s hybrid vision becomes widely adopted remains an open question. But, as Pennarun says, “We are trying to set a new direction for the internet. We’re currently leading the charge. If another company beats us there, it may be a little worse for me, as a business owner, but it’s still better for everybody who uses the internet. And that’s ultimately what matters.”