The Frontier Interview—Dan Leers on “Widening the Lens”

On the definition of photography, sensing rather than seeing landscapes, and museums as drivers of sustainability and community

Hi everyone,

For about a decade I worked as a photography critic, as an editor at Aperture Foundation, and (as mentioned last week) as a curator of photography at an art museum. I still turn to photographers—and artists using other lens-based techniques—for insights into how we relate to landscapes and the built environment.

One of the exhibitions I’ve most looked forward to this past year is curator Dan Leers’s Widening the Lens: Photography, Ecology, and the Contemporary Landscape at Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Museum of Art. So last week I spoke with Leers about the show. Our conversation touched on artists using other sensing techniques—not just lenses—to record landscapes and the dangers they face, how the term ecology might help us rethink our definitions of sovereignty, and how art can help us see both the promise in and the perils facing the places we inhabit.

Has a photograph or a body of artwork changed how you understand a place that’s important to you? I certainly have my own examples; hit reply or comment below and let’s share.

Until next week,

Brian

Takeaways from this week’s interview

- Conventional definitions of photography—and of a camera—no longer fit reality. From ultra-high-speed cameras to computer models that generate imagery to “cameras” meant to capture and interpret signals with no humans in the loop, it’s time to update how we think about the medium.

- Landscape photography encompasses more than the sweeping vista. Artists working in the genre today are as likely focus on shabby urban patches as they are glorious mountains at dusk, and what you see is not always what the artist wants you to get.

- Museums can support artists, but can also use that support to further broader agendas. Production budgets can enable the creation of ambitious new work, but can also be a lever for thinking about sustainability.

Good links

- 📕🏗️ Two weeks ago, I wrote about Lloyd Alter's new book Upfront Carbon; now Azure Magazine has published an excerpt from its introduction

- 🏢👀 Buildings that caught my eye this week: Fragmentos’s sensitive and skillful renovation of a small Lisbon apartment building; J. AR’s unification of five light-industrial buildings on the Gold Coast south of Brisbane; UNStudio’s blocky & flexible apartment building in Munich

- 🇺🇦🏛️ New York Times critic Jason Farago has been admirable in his focus on Ukraine: the culture war, the role of art, protecting cultural heritage, how museums are responding to the war, its experimental music, and more. Now he’s written about “how architecture became of one of Ukraine’s essential defenses.”

- 🔊🍸 While we’re on the subject, I’d love to visit this new music bar/listening room in a hotel in Kyiv

- 🌿📃 “The International Indigenous Design Charter is a living document for the best practice protocols when working with Indigenous knowledge and material in commercial design practice.”

- 🌏🎨 Jessica Spresser offers notes on SANAA’s Sydney Modern, one year after it opened

Nothing Lives Alone

Brian Sholis: There have been many fine recent surveys of American landscape photography, perhaps most notably Sandy Phillips’s American Geography. But as thoughtful and critically minded as that project was, it still focused on photographs—singular printed images captured through a lens. The title of your show suggests that photographs may be too narrow a way of sensing our landscapes and the dangers to them. Can you elaborate on your inclusion of so many artworks that are not simply photographic prints?

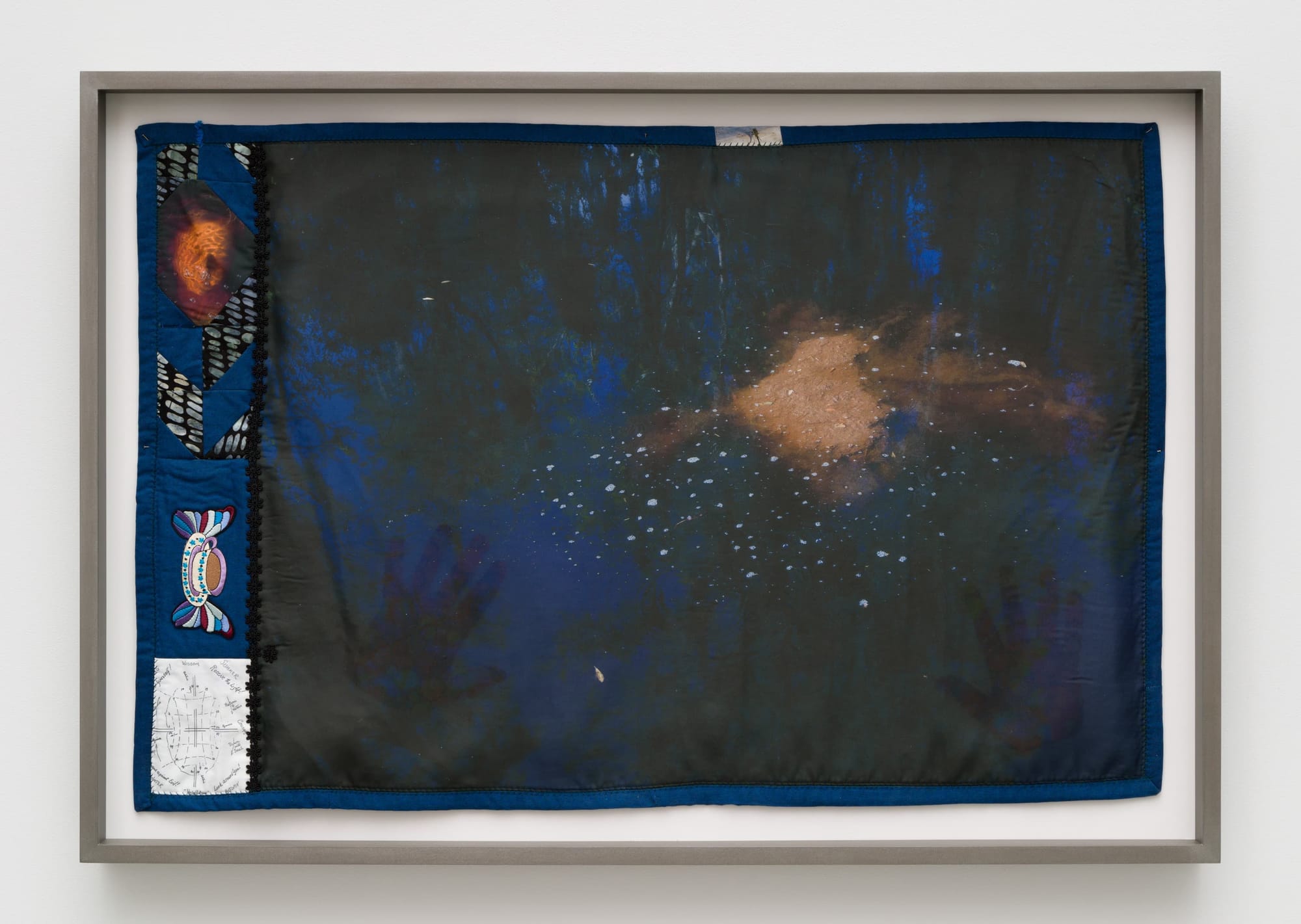

Dan Leers: It’s just that. The show challenges not only the notion that we need more than photographs to understand the layers of meaning in a landscape, but also the definition of a photograph. For example, we commissioned Lucy Raven to make an artwork, which is essentially silt—dirt—on silk that was lining a hydrological modeling tank. There’s nothing “light-sensitive” or “lens-based” about that work. Yet it tracks the movement of material over time.

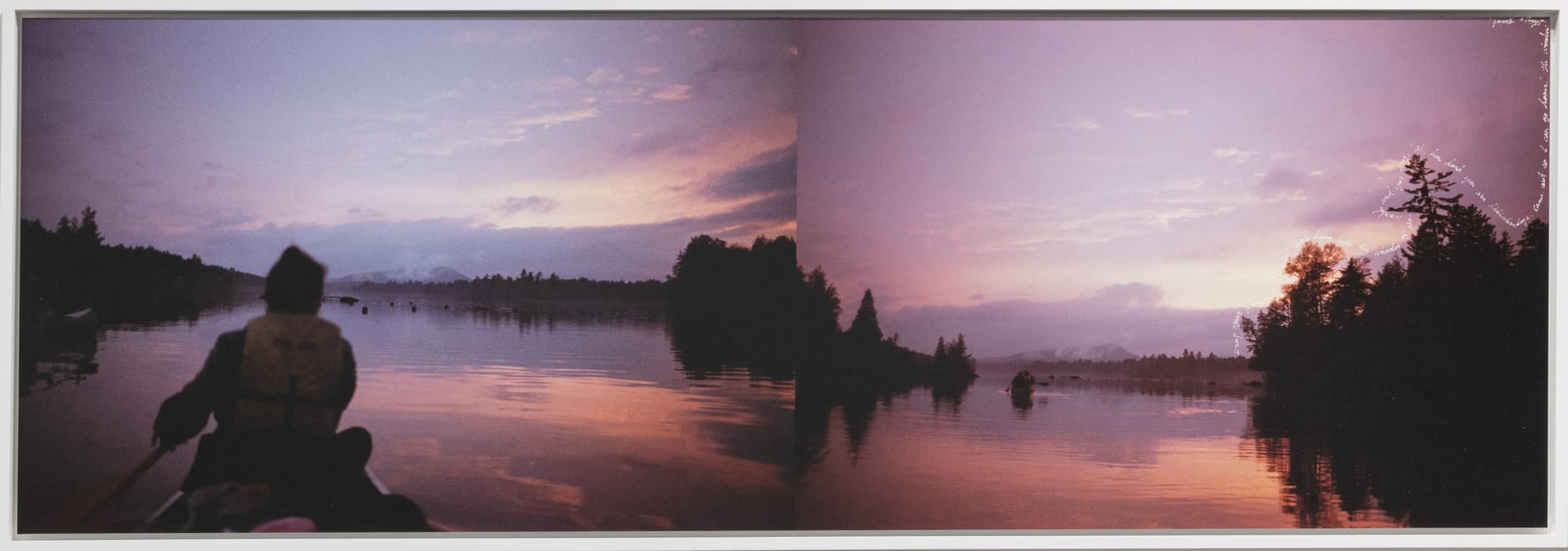

To understand the more abstract—or in some cases poetic—elements of developments like the largest removal of a dam in America, which is happening right now on the Klamath River, you may need more than just pictures of the river. To create another work in the show, Raven used a scientific camera that takes seventy thousand frames per second to make a video in which an algorithm compares the second frame to the first, the third to the second, and on for millions of frames after that to reveal the changes created by an explosion. What we see isn’t the explosion itself, but how it sends ripples through space—so in some sense, she’s also denying us the polite fiction that photography reveals something truthful about the world by showing us everything that comes after the explosion. The work is, quite literally, moving images.

To me, these fundamental questions about photography remain very rich areas for exploration. Not just who’s behind the camera, or who or what is in front of it, but also what gets left out—and understanding that there are many other perspectives on the same subject.

BS: There’s a famous book of social philosophy, published thirty years ago, called Downcast Eyes. Its subtitle is “The Denigration of Vision in Twentieth-Century French Thought.” It’s interesting to think that this critique of the supremacy of the visual is coming now even for photography …

DL: Yes, and this is something Eva Díaz discusses in her contribution to the catalog. Some wonderful artists are trying to challenge the primacy of sight in photography, trying to disrupt it.

BS: Returning to the title: it seems to me that your use of the word ecology is a pointed rejoinder, of sorts, to similar projects that talk about “the environment.” Can you talk about how ecology is meaningfully distinct from environment and why you chose that term?

DL: First, ecology is much more holistic. We also cite the scientist Ellen Richards in the catalog, and she situates the term in a domestic context: “Let ecology be henceforth the science of normal family life.” I take that to mean our whole home, not just our houses; all beings’ lives, not just our singular life.

The term also pulls in questions of sovereignty—which are far more interesting to me than questions of ownership. We are loathe to recognize the sovereignty, for example, of plants and animals; we’ve mentally separated ourselves despite being … well, animals. I hope that we can reinsert ourselves into broader contexts a little bit through the term ecology. If we can think just a little more symbiotically, be a little more aware of what’s around us on a day-to-day basis, those small changes theoretically can resonate outward and have large implications.

BS: I also take the term to resonate not only with scientists, but also with the Indigenous prioritization of relationships, of things being-in-relation.

DL: Absolutely. Patty and Ben Krawec, who contributed to the catalog, also came for the opening of the exhibition and led a fascinating nature walk around the museum’s campus. They pointed out indigenous species, edible species, invasive species, and in doing so reminded us that when we consider landscapes it should not just be sweeping vistas, but also the places where we live and work.

BS: Before recording, we chatted briefly about how your museum has a community archivist on staff who researches the histories of objects in the collection with local connections. What you just said connects back to that, for me, in the conventional understanding of the museum as a place that’s set apart—it has a campus, it has climate-control regulations, it has a conservation lab. Perhaps this notion of a museum is counter to the notion of ecology, and in another generation we may be talking even more about how to make museums more porous—and that we might see new ways of making and operating museums that today’s conversations cannot conceive.

DL: I think that’s an important point. We’re not there yet. I tried to nod to it, in part, with the Edra Soto commission. Her work as an artist is about liminal spaces, and the photographs she has inserted into this large structure are about tracing the lines back toward the roots of her existence, the things that connect Chicago and Puerto Rico, connect generations of her family. When we began talking about her piece, with its wonderful title El Destino, part of the conversation was about lowering our exhibition’s carbon footprint and what we could adapt. She had built a large structure for the Chicago Botanic Garden and ended up outfitting it with viewfinders that allow you to see her pictures. In our galleries, you can still see the watermarks from its earlier presentation; she’s quite literally moved this artwork, which represents her home, into the museum. People can touch it; they have to interact with it.

This is also a noisy exhibition, one where you can touch things, where you find little secrets. My hope is that this models ways we all can think about new museum experiences.

BS: Another idea in the exhibition that I think will be new to many people is one you mention in your own catalog contribution: the paradox that, in the United States, expansionism and environmentalism go hand-in-hand. You were talking about nineteenth century photographs of the American West, which both encouraged the opening up of territory for settlement and the protection of it by setting it aside for conservation.

DL: That nuance and complexity, in some sense, helped me with the show. I found myself having to make sure I wasn’t being too pessimistic, that questions about landscape aren’t all doom and gloom—that good can come from paying attention to landscapes, not just despoliation.

I talked earlier about symbiosis, and I needed to remind myself that we’ve had more symbiotic relationships in the past—which suggests the possibility that we can have them again in the future. We feel like we’re heading on a certain path, but, again, I believe we can make little and big changes that alter our destination. We can hold two ideas in our mind at the same time, find pictures or artworks beautiful while also recognizing they chart places that are being harmed. Finding the balance that enables action is really important.

BS: There’s one more line from the catalog that struck me. The eminent writer Lucy Lippard, in what I think of as a provocation, says, “The bottom line is that you can’t own a place, you can’t belong to it, and maybe you shouldn’t even be shooting it until you take some responsibility for its fate.” You’re not a photographer, but after having worked on this show for years I’m curious to hear your thoughts on this invocation of responsibility.

DL: I’m not going to lie: Lucy and I had a back-and-forth about that line. But it’s also why we wanted her to write—in addition to being so thoughtful she’s good at stirring the pot. As for responsibility: we tried very hard to put in place policies that lowered our carbon footprint. One of them is that, wherever possible, we used exhibition copies of photographic prints. It may seem odd to make new prints for a show, but doing so often means less overall shipping: consolidating objects into fewer shipments, reusing the prints for tours, even returning them to the artists to be used in the future.

Museum curators often talk about putting budgets toward creative production, for example by commissioning artwork. We’re delighted to help artists realize visions they otherwise would not be able to—

BS: But that also gives you the power of the purse, so to speak, where you can help realize the work in ways that serve broader (ecological) agendas.

DL: Yes. We wanted to at least let the pictures have a longer life than the six months or however long they’ll be on view within this exhibition.

BS: You’ve previously done shows in Pittsburgh with Trevor Plagen and An-My Lê, both of whom attend closely to landscapes. Is Widening the Lens a culmination of this abiding interest in landscapes or simply a way station in your thinking about the subject?

DL: I never want to say “this is the culmination,” so I’ll broaden it further to say that the show is part of my desire to create programs that connect to questions and conversations I’m having in my personal life, that my colleagues are having in theirs, that we’re all having in dialogue with members of our community. I want to keep making shows about what we care about. I want to give artists a platform to express eloquently about what it’s like to be a human being in today’s world.

BS: And it just so happens that artists who turn to landscapes repeatedly crop up in those conversations …

DL: I guess so. You know, I probably need to go to therapy to figure that out, rather than in an interview.

BS: Fair enough! A final question about the catalog, since that’s how more people will be able to encounter the show and its ideas. The design is handsome, but seems also to deliberately communicate environmental awareness: most of it is printed in one color on untreated kraft paper, most of the color photos are tipped in to save on paper, and the like.

DL: Yes, all that was intentional. Also, since a lot of the work in the show is more than just framed photographs on a wall, we wanted the book to be a tactile or sensory experience akin to what you get in the show itself. You flip through the book, unfold pages, turn things over—we hope it communicates a message of discovery, of finding things that are hidden or buried. The book has strata, like a landscape, that disclose themselves to you if you dig deeply enough.