Bringing It All Together

Our fleeting passions make up our lives

Hi everyone,

Near the end of his new essay collection, Affinities (buy via Bookshop or Indigo), the Irish critic Brian Dillon notes the “many dream states in which for a time not much else matters but the word, sound, or image at hand and what it seems to teach you.” This episodic infatuation has been my own experience of art—the visual art that was for a long time my professional focus, but also film, music, and writing. It is also, in some sense, a way to make sense of a life, for our cultural affinities run alongside and are entangled with romances and friendships that bloom and then fade, places that capture our hearts but which we do not revisit, and hobbies that occupy hundreds of hours before we put them aside. Dillon’s extended riff on the term affinity, parceled out in ten pieces alongside considerations of images that have enraptured him, gives this collection deeper resonance. Not only does Affinities offer his insights into a range of European and American artists, but it also encourages us to reflect upon which obsessions make us who we are.

Dillon’s primary obsession, whose shape he recognizes after collecting these essays, surprises him. “If asked what I value most in art, in photography especially, I might not have said: a state of bodily between-ness verging on dissolution, aspiring to reconvene otherwise, in alternative forms. Sometimes it’s a question of visual texture,” but often it’s a way the artist herself disappears into the work. He perceptively discusses Claude Cahun’s exaggerated self-presentation, Francesca Woodman’s tendency toward “veils and avoidance,” and Julia Margaret Cameron’s “deliberate effort to capture something evanescent but particular.” His essay on Cameron is one of the longest in the book, giving us her biography, wonderful descriptions of her pictures, and an insightful comparison to her great-niece Virginia Woolf: “what the two women shared was an artistic struggle to render as closely as possible certain fluxual states or … moments of being that threatened to turn into abstract blurs.”

The reference to Woolf betrays Dillon’s training in literature, and Affinities is the third book in a series that began with Essayism, his 2017 exploration of the genre’s fluidity, and Suppose a Sentence (2020), which gathers and analyzes exceptional fragments the way this book does single and singular images. In each, Dillon shines the intense spotlight of his attention on a great body of artworks—or perhaps it’s better to say, since his selections are limited by both page count and his taste, that his attention creates glints on the surface of the vast ocean of cultural artifacts. This book is arranged chronologically, from a seventeenth-century view through a microscope and an 1838 street view, one of the earliest known photographs, to the “calmed and precious world” of Japanese contemporary photographer Rinko Kawauchi. The arrangement underscores the idiosyncrasy of, and the large gaps in, Dillon’s “history”—which again reminds us that it’s a personal one.

Perhaps Dillon’s approach, which in my own life I shorthand as a preference for “atmosphere over argument,” isn’t for everyone. In one amusing, self-deprecating passage, he describes delivering a talk in graduate school: “A junior academic raised his hand and said this was all very well but seemed to consist only of connections. Where were [the] judgements and distinctions?” I believe firmly there is value in Dillon’s approach, in collecting fragments without resolving to unify them, in sitting with connections and adjacencies. He has no polemical argument, no axe to grind. Dillon is not writing like art historian Michael Fried, lining everyone’s photographs up in service of a half-century-old idea. But in constructing these webs of affinity, he does something more like what all of us do: he integrates his observations, reactions, feelings, and moods into the varied textures and patterns of his life.

As with the other two books in the series, Affinities reveals details about that life: his first encounter with a migraine; his mother, ravaged by disease, exchanging “prayers with a countrywide network of the pious and the desperate” before dying aged fifty; his aunt Vera, troubled in her later years by the imagined trespasses of her neighbors; parts of his pandemic experience. These stories, often touching, ground his essays on art in the life that shaped his sensibility. And they teach us to look for such connections between our lived experiences and our work. As he writes about his mother’s tormented sister: “If I cannot exactly sympathize with her anxiety and aggression, I understand perfectly her methods and the state of mind necessary to such a protracted act of close looking.”

Riffing on the poet and painter Wayne Koestenbaum, another writer for whom identification often turns insightfully excessive, Dillon writes, “Affinity exiles us from consensus, from community.” We each create our own little worlds, with their own stars in the sky. In mine, the writer Marilynne Robinson, the musician Tim Hecker, the architecture firm Barozzi Veiga, and the type designer Kris Sowersby all shine brightly. Yours is entirely different. But the feeling I had as I finished this book is that affinity, as a way of seeing and understanding the world, also points to a larger unity. We all have the capacity to be affined. We seek meaningful relationships with others at a time when we live far apart from the people we love, when work can leave us feeling alienated, and when public discourse often has a fragmenting effect. In these conditions, our capacity for finding shared interests, for creating community based upon the acts of creation that inspire us, is all the more important.

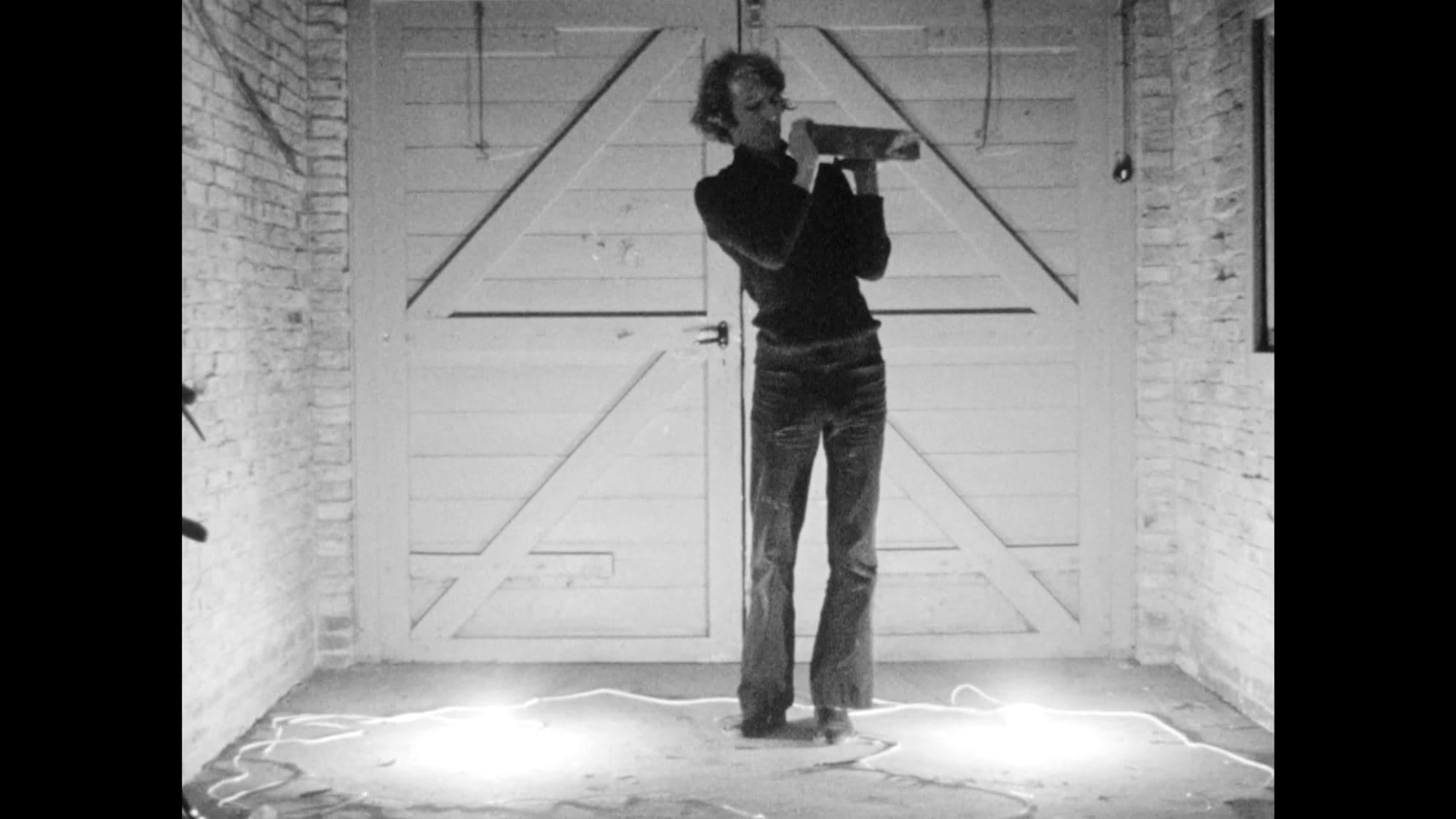

Let me end, as I’ve come to do in these weekly notes, with a little story. In this book Dillon suggests that, “if I were pushed to say what is my favorite work of art, at least some of the time I would have to name” Andy Warhol’s film Outer and Inner Space. It’s a fun game. Today I’ll say that mine is Bas Jan Ader’s short film Nightfall. It has a premise so simple you might call it idiotic: standing in a small garage, with bare light bulbs resting on the floor to either side of him, the Dutch artist holds a large brick or cement block at shoulder height on one side of his body. We watch as he struggles to keep hold of it. When he drops it, it crushes the bulb and half the light in the room goes out. Then he picks it up and holds it on his other side. We know what will happen next, and it does.

It’s been at least fifteen years since I’ve seen the film, but I can distinctly recall so many of its details. It’s an experience I’ve held on to. I can’t—or, more honestly, won’t—say what it means to me. But I’d love to know: what artwork, what cultural experience, has meant so much to you that you’d label it a favorite? Write back. I’m here, in my home office, developing new obsessions.

Love all ways,

Brian

🔗 Good links

- 🌬️ Jeff Wall’s magisterial 1993 photograph, A Sudden Gust of Wind (after Hokusai), has been re-created in a “book” edition that you can hang on your wall

- 📀 A ten-minute video introduction to the enigmatic and extremely talented musician Jai Paul, who played his second-ever live show at Coachella last week

- 👨🏻💻 “I want to write a novel but instead of a book, it takes place across the internet.” Dan Sinker on a new collaboration with writer Joe Meno.

- 🎵Musician and producer Damon Krukowski on taking his studio completely offline