Erin Kissane

On infusing technologies with an ethic of care

Episode Transcript

Erin Kissane: We really tried to treat everyone inside and outside of the project like real human beings with real lives and needs. Our caution and our neutral tone were an expression of our really intense desire to not traumatize the people we were trying to inform any more than they had to be traumatized, to try to give them information that would allow them to make decisions about their lives in the least damaging way possible.

Brian Sholis: Hi, I’m Brian Sholis, and this is the Frontier Magazine podcast, where I interview artists, writers, technologists, architects, and other creative people about their work and the ideas that inspire it.

Today I’m speaking with Erin Kissane, a writer and editor whose ideas on technology, community, and networks I’ve engaged with for nearly twenty years. Once an editor at A List Apart magazine, she has also been an editorial strategist at studios like HUGE and Happy Cog; helped data journalists, designers, and reporters at OpenNews; and, in 2020 and 2021, co-founded and was managing editor of the COVID Tracking Project at The Atlantic. Across the decades, Kissane has brought humanity and humor to a technology industry that often lacks both, and, as this conversation makes plain, infused her work with an ethic of care.

You can learn more about Frontier Magazine and subscribe at magazine.frontier.is. Thanks for listening. And now, my conversation with Erin Kissane.

BS: I’m currently the editorial director of a design studio and it’s a position that still sometimes prompts confusion. But you held similar roles nearly twenty years ago when you worked at a couple of rapidly growing web and design agencies. I wonder if you can just talk a little bit about what led you to that early work in a studio setting.

EK: I just followed the needs that became visible. I’d been editing A List Apart Magazine, which was focused on web standards, but also on design and implementation ideas that circled around cross-browser work, work that was always accessible. So I’d been, because of that work, pretty far down into some design and engineering conversations, and had gotten to know a lot of people who were doing those kinds of projects from a more traditional design or information architecture or front-end background.

And it turned out that a lot of those projects needed editorial thinking and a lot of the clients didn’t have someone on staff to do that. How can we find you the right person? It won’t be the editorial director of the studio, but maybe that person can help you come up with a publishing plan, with a sense of, you know, what your actual strategy is.

I am only interested in the internet and in our networks inasmuch as they are useful to people and inasmuch as they are useful specifically in solving big problems, rather than causing or worsening big problems.

BS: I think of you as one of the earliest editors and writers who ended up tackling technology as a kind of intellectual pursuit outside of journalism, outside of tech journalism. One of the first people to start thinking through what everything that was happening actually means for us as a society, means for us as individuals. And I wonder if that interest came as a result of this early work that you were doing with agencies and with A List Apart, or is it something that you’ve always been interested in and then found your way to make a career with that as its thematic or intellectual focus?

EK: I can’t help thinking about those things. And I think because I’m a writer and an editor, what I do about that is write things and try to get other people to write things, which sometimes I edit. I got into web work in the very late nineties, coming straight out of undergrad, because it seemed genuinely important. The potential of what was about to happen on the web seemed huge to me. And also I got fairly concerned really early on with accessibility. I was more concerned about the implications of things like what we used to call the browser wars, the court politics that were happening on the browser side. And I think that period is where I developed my really deep suspicion of corporate, extractive approaches to the web.

So that came in very early. And unfortunately, it hasn’t usually been the wrong instinct. I came in from that angle because it seemed like a place where I could use my brain to perhaps be helpful to more people. I am only interested in the internet and in our networks inasmuch as they are useful to people and inasmuch as they are useful specifically in solving big problems, rather than causing or worsening big problems.

BS: I think that the use of your brain, as you put it, to help other people ensure that they aren’t crushed up by the gears of the machine is what attracts me to your thinking and your writing.

So about a decade ago, you helped write a code of conduct for a conference that your organization was hosting. But then you also wrote about the process of making it and why you feel that every event should have one. And I kept thinking about how conferences are limited in time and they’re limited in scale. And I wanted to ask you, what is the relationship between a code of conduct for a conference and the terms of service on a larger social-media platform? Is there a ceiling on the number of people that a code of conduct can meaningfully apply to?

EK: That’s such a good question. It’s the kind of thing that I’ll probably chew on for a while. I mean, I think that basic requirements for behavior on a network aren’t that different, necessarily, from requirements for behavior in a building. But I think where things get really complicated is when it comes to how you actually make the code of conduct or the terms of service real in the world, what you do with it. And, especially for big-world networks, how you localize, how you handle the complexities of—I mean, honestly, nation-state actors who want different things from your network and all of the sort of cultural literacies and illiteracies that come along with this work.

The really big global platforms do have another whole level of complexity beyond even how do you handle things like making sure that if you make a rule, it is fairly implemented and equitably implemented and you’re not actually using it to sideline or discipline people who very frequently happen to be marginalized for other reasons. Is that an answer? [Laughs]

BS: It is, it is. I mean, one of the things that I think about in what you wrote about designing a code of conduct is that a proactive statement in itself is never enough and that it requires so much behind-the-scenes wrangling and then behind-the-scenes commitment and enforcement once an event has begun. And that’s also where I begin to wonder whether there is an upper limit on just how large of a community those kinds of policies, those kinds of statements can begin to properly encircle and care for.

EK: I think it’s a really relevant question for our moment because, obviously, human-scale community is quite different from global platform scale. I think, in practical terms, a lot of what happens on really large platforms is that sub-communities form and develop their own centers. And you see a certain degree of peer moderation happening within those communities. But again, it’s not all evenly applied. Some communities work better in some kinds of terms of service and trust and safety institutions than others. So I myself am worried about content moderation specifically as a model at scale. I think so are all of the people who do content moderation. I think those things are messy, but those I think are good questions to be asking. And I think there is a lot of good thinking happening within trust and safety as a field, which is becoming, I think, more conscious of itself as a field. I don’t know what will happen, but that’s where I think a lot of the most interesting questions on the whole internet are right now.

BS: The largest platforms, which we perhaps took in some inertial way as being permanent, some of them have proven themselves to not be permanent. And, in fact, change is the only constant. And in that change comes the opportunity to rethink these norms.

EK: Yeah.

BS: I want to take a detour into your experience with the COVID Tracking Project. And I wonder if you can just start by briefly explaining what that was and why you both felt it was necessary to start. And then also what it meant to be the “managing editor” of such an effort.

EK: So what happened, if we all rewind back to the very, very early days, when it was very hard to tell if there was going to be a pandemic, I was texting with my friend Robinson Meyer, who at the time was at The Atlantic, along with Alexis Madrigal. And we were talking about what we were concerned about. I knew that he was trying to get a sense of what was actually happening here in the US, where we both live. And somewhere in those first couple of weeks where he was poking around, he mentioned that the question that arose—I think naturally for a journalist—is, “Well, how many people are we testing?” Because if you’re testing ten people and you have three positives, that’s really different from if you tested ten thousand and you’ve had three positives. And it was really difficult to find the answer.

So, um, he and Alexis started calling all the states to find out how many tests they were doing and put together a spreadsheet of their responses. There were a couple of states at the time who had started to publish things on their websites, but this was super, super early days. Once they had the answer, which was we’re hardly doing any testing at all, they realized they needed to do it again to find out if the numbers had really changed dramatically. And around the same time, it turned out that someone Alexis knew from his undergrad days, Jeff Hammerbacher, had separately made his own spreadsheet. Alexis and Rob realized that they weren’t going to be able to continue doing a daily scrape-and-call operation. So they decided to open up to a handful of volunteers and they posted a link. And I was apparently literally the first person to sign up. I was very interested in helping figure out those numbers. I think I told them I had like two hours a week available for a couple of weeks. Everyone involved thought the CDC was going to start publishing that information really soon.

So that’s how I came on. And in those first couple of weeks, I wound up being someone who helped build out the website, build out some processes, figure out how to onboard people, and what kind of communication we wanted to do with the information we had. Initially, we only were targeting other media organizations because we knew that most news orgs didn’t have that information. So that was the initial plan. And I don’t think any of us expected it to go for longer than two weeks. And that turned into by far the most full-time thing I’ve ever done in my life for a little more than a year.

BS: Tell me, what did “the most full-time thing” look and feel like?

EK: What it turned into was, first, many times a day and, eventually, down to a single-day pass across datasets in fifty-six US states and territories to pull together the numbers. And then increasingly our work became trying to understand the different numbers that states were publishing because it turned out they were not all publishing the same metrics. So we were onboarding dozens and then hundreds of people to help go and collect the digits, but then we had to bring in public health expertise to help us understand. And then we wound up running that data set for, like I said, for the first year, really, of the US experience of the pandemic. And it was something that hundreds of local and regional and national and international media outlets used.

It turned into a whole institution. No one came in to run a crisis data project that would get used by two successive, very different presidential administrations and get read into the Congressional Record and all of that stuff. None of that was the plan. So that was the least strategic move I’ve ever made in my life, career-wise, but also the most meaningful work imaginable.

We really tried to treat everyone inside and outside of the COVID Tracking Project like real human beings with real lives and needs

The thing that I came out of the COVID Tracking Project with was so much more optimism than I had ever felt about the possibility of what could be done on the network. All of that work was done remotely. Literally hundreds of people skilled up to do that work purely for altruistic reasons. So I came out with a sense that there is a lot that we can do together.

BS: There’s so many things in there that are good to hear. I was struck by a lot of the things that you said in the kind of summative essay that you wrote as you wound down the project. You described some of the principles that you as a group adopted about being intentionally narrow in the scope of what you tried to do, being as transparent as you could be, having a kind of interpretive caution and not wanting to hazard too many guesses about what the data you were collecting actually meant, having a commitment to context and to caring for your people, this network of staff and volunteers. You know, you structured your efforts in that way partly because of the magnitude of the work and its importance and the difficult circumstances in which you undertook it. What did you learn through the COVID Tracking Project that you wish you could apply to your future work or that you wish that more people would apply to the ways they come together to achieve coherent goals?

EK: The crucial things to me, especially from a distance, were that we really tried to treat everyone inside and outside of the project like real human beings with real lives and needs. Our caution and our neutral tone were an expression of our really intense desire to not traumatize the people we were trying to inform any more than they had to be traumatized, to try to give them information that would allow them to make decisions about their lives in the least damaging way possible.

So on the one hand, it’s about credibility, but on the other hand, which is perhaps a more important hand, it was about taking care. That was an outward-facing form of trying to care for people. And I think what was visible on the inside was a culture that really prioritized care. We had to chase people out of the project after they’d been on for too many days in a row because they wouldn’t take breaks. We had to send people away. I had to threaten to turn people’s Slack accounts off so they would go get sleep. But a lot of that was also structuring the project so that no one person was responsible for something crushing, that they had layers of protection.

You know, obviously it started with a desire to let people know what was happening in the world. And that was always the center of it. But the way we did it was with an eye toward care. That’s maybe the most important principle in this work. What if you were actively attentive and careful and cautious and kind to scared people? What might happen?

And I think the answer was way more than could happen in any other circumstance. You know, there are all these ideas that we have that we’ve been sort of professionalized into from so many jobs that are about wringing productivity out of ourselves. And I think what we saw at CTP was the exact opposite. The more attention and care we put into trying to treat everyone who worked on the data like real, full human beings, the harder those people worked. Like, we couldn’t have extracted more productivity if we’d tried, but that’s not what we were trying to do. We had to treat people like that because they were volunteers doing a crisis project. Having done that, I think that’s the only way to treat anyone, including employees, including anyone you’re working with in any situation. And I recognize that that’s not necessarily reflective of our moment in technology, which is going through a series of mega layoffs and pushback against labor in general. But I’m a believer, having seen it work at scale with the most motley crew of people. We came from everywhere. These were not necessarily all folks who were aligned in any other way.

BS: You described it early on as maybe the least strategic decision about your own career, but it’s also one that seems, in your answer to that question and in the way you wrote about the conclusion of the project, it seemed perhaps the effort of yours that most relied on strategy, deliberation, strategic thinking, and ensuring that care is built into the work that you did. Maybe I can connect this back to the conversation we were having earlier about social networks and large-scale tech companies and trust and safety by asking, you know, what, if anything, connected the state and federal governments’ early haphazard attempts to collect and share COVID data with the approaches to trust and safety that are exemplified by the biggest tech companies. Was there any kind of throughline that you saw just when an organization, whether it’s governmental or corporate, is working at such a scale?

EK: That is another really excellent question. I don’t know that I would have said that I had a sense of that after COVID happening, but hearing you ask it, I think the really strong temptation for any institution, especially of a large size, to refuse to allow itself to know and understand important things about its effect on the world. That may be a kind of an opaque thing to say, but I’m thinking here specifically about the CDC. The CDC really did not move on the communication and data side in a way that I think was commensurate with what was happening. It didn’t move in a way that matched up with the emergency situation on the ground. I think that is a consistent problem through to now that has never been fully dealt with. It’s pretty clear that similar things have happened with the big platforms. And I’m thinking here very specifically of Facebook and Twitter in the way that they have not permitted themselves to understand or address their real harms in the world in a way that is commensurate with the scale of harm.

I think we need to really root our work in co-design, in the design-justice movement sense, with the people who are at risk of harm from the things that we’re making.

BS: I asked that question connecting the government and the largest tech companies because there is this cliché that the largest tech companies, they have a GDP that’s equivalent to whatever European state you want to choose, that they are in a way almost sort of like state actors in and of themselves. But also because you, after a two-year break after the COVID Tracking Project, have returned to write on the design and implementation of social platforms, and in particular to write about what healthy social platforms might look like. You have written that many people attribute the problems and sometimes the successes of social media to systems, on the one hand, or to personalities, on the other. I take it that you think that that’s a false dichotomy.

EK: I think what I’m trying to get to there and in similar formulations is if we say, “It’s human nature, that’s just how it’s going to go. The problem is people. What can we do?” I think that’s really letting our systems off the hook. Obviously our systems were made by people who may or may not have good personalities and by groups of people who as corporations may or may not be good. But I’m just really leery of both ends of that. I’m super interested in that fuzzy space in the feedback loop between various kinds of personalities making systems that then affect how we behave toward each other. What are some ethical ways to work with vulnerable people and communities to come up with tweaks that we can try?

As an industry, generally in tech, a lot of us are tinkerers. We are people who want to try things. We are people who want to jump to potential solutions and give it a shot. And that can be good in some circumstances, but if you’re talking about systems full of people, especially if you want them to then work at mass scale, I don’t actually think it’s very responsible to jump directly to, “Hey, this is a possible solution.” I don’t think that’s where we should be in 2023 with, for instance, large-scale social networks. I think we need to really root our work in co-design, in the design-justice movement sense, with the people who are at risk of harm from the things that we’re making.

In the same way, I think that as we build platforms and systems and tools, we need to find ways to keep ourselves as individuals and institutions open to fully hearing feedback, including things that we don’t like, that we don’t want to hear, that suggest that we’ve gone in wrong directions. That’s tricky, keeping your balance when you’re trying to move forward, not letting yourself be overly influenced by a few loud voices, but also keeping open to real feedback.

There are so many people who are desperate to make any kind of positive contribution to the world. When things get bad, people want to help.

BS: There is a distinction to be made between moving forward on the one hand, moving forward with your users, moving forward with vulnerable communities, and figuring out ways to ensure their safety and the health of the spaces they inhabit, and moving fast on the other hand. And when you move fast and break things, I think what tends to get broken are the exact same things that other systems have already broken, that it compounds harm. Design is something that involves creativity, but it’s something that needs to be done with care, to go back to the word from the COVID Tracking Project.

EK: Right.

BS: I work for this company that has a thesis that creativity and great design can accelerate positive change. And I think you’ve said something similar, that there’s a version of making a better world that involves maximizing health and maximizing safety to the exclusion of everything else. And therefore you end up designing social networks that don’t necessarily work or certainly don’t delight. And you know, you wrote that it’s up to us to make these safer experiences delicious and convenient and multi-textured and fun.

EK: Yeah.

BS: What kinds of experiences are you looking for and most hopeful about, if any, in September of 2023? What characterizes them?

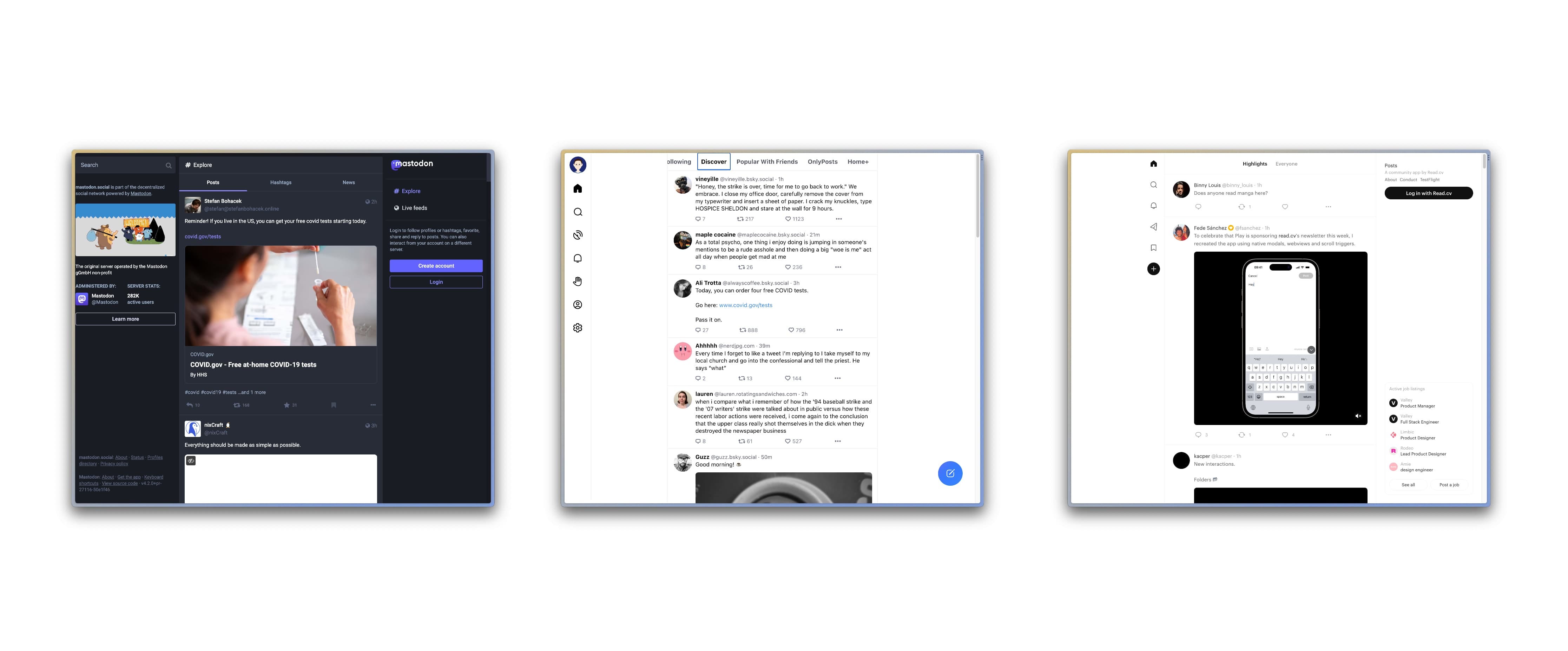

EK: I think there is a ton of wide open space. I think this is a really exciting moment for people interested in what I think of as the product design side of all of this. For a long time, it really felt like things were locked down. The overwhelming monopoly that big platforms had on the social side of things, on many sides of things ….

And as you said, they are clearly in a moment of fragmentation or dissolution. I think those moments are always brief. So I actually feel quite a bit of urgency right now. But I think also it is not actually that hard to do something that is exciting and also ethically grounded right now. You do have to, I think, make the commitment and the time to understand the people and the situations that they’re in and the problems that they face. But that’s always the case with good design.

So yes, there is this crunchy, difficult work to do, but also, to me, we’ve been kind of locked into some pretty repetitive, very restricted forms in these big networks for a long time on the internet, a very long time. I’m really excited about new kinds of interaction. One of the things to try to sort of tie this together. One of the big things that I came out of the COVID Tracking Project with, is that there are so many people who are in fact desperate to make any kind of positive contribution to the world. When things get bad, people want to help.

And you know, if you read Rebecca Solnit, if you read anyone who’s done disaster scholarship in these ways, this is not a new idea. People want to help. And Mike Davis, who’s sort of a beacon for me, talked about this as un-mobilized love. There is so much un-mobilized energy and attention all over these networks. And mostly the way our platforms and tools have been built takes advantage of very little of it. We’ve seen a lot of systems that optimized for engagement; that’s because they’re advertising systems. So they had their specific goal, which was to maximize the extraction of money from companies via advertising. What happened to the people in the systems was basically beside the point.

Our open new tools don’t have to be that way. What are the things that we can build—as product design folks, as engineers, as … editorial nerds, maybe—that provide new forms, that let people put some of that un-mobilized love to work, to actually help each other and to build solidarity instead of dissolving it? This is an incredible moment to be working in online design.

Thanks for listening to the Frontier Magazine podcast. It’s the audio component of our weekly publication, which features appreciations from the forefronts of architecture, technology, culture, and education. Each issue shares new ideas about how design and creativity accelerate positive change. Everything we publish is available for free; browse the archive and sign up for new issues at magazine.frontier.is. If you liked this episode, please share it with people you know and rate us to help others discover what we’re doing.

The magazine and podcast are products of Frontier, a design office in Toronto. Here’s studio founder Paddy Harrington:

Frontier is a design office. We believe in the expansive potential of storytelling to help people navigate the unknown to get somewhere new. We’re coming up on a decade of designing big stories in the form of strategies, brand identities, editorial products, and digital and real-world experiences that help organizations, brands, and individuals stand out and discover new creative territory. Learn more at frontier.is.

Thanks again. I hope you’ll join us for the next episode.

This episode was produced by Heather Ngo. It features edited versions of “Thwarted Motion” by Ejeebeats, “Dreamy Ambient Loops” by Memomusic, “OXY” and “VHS” by Joel Loopez, and “Hybrid Tech Theme” by Geoff Harvey.