Historical Renovation

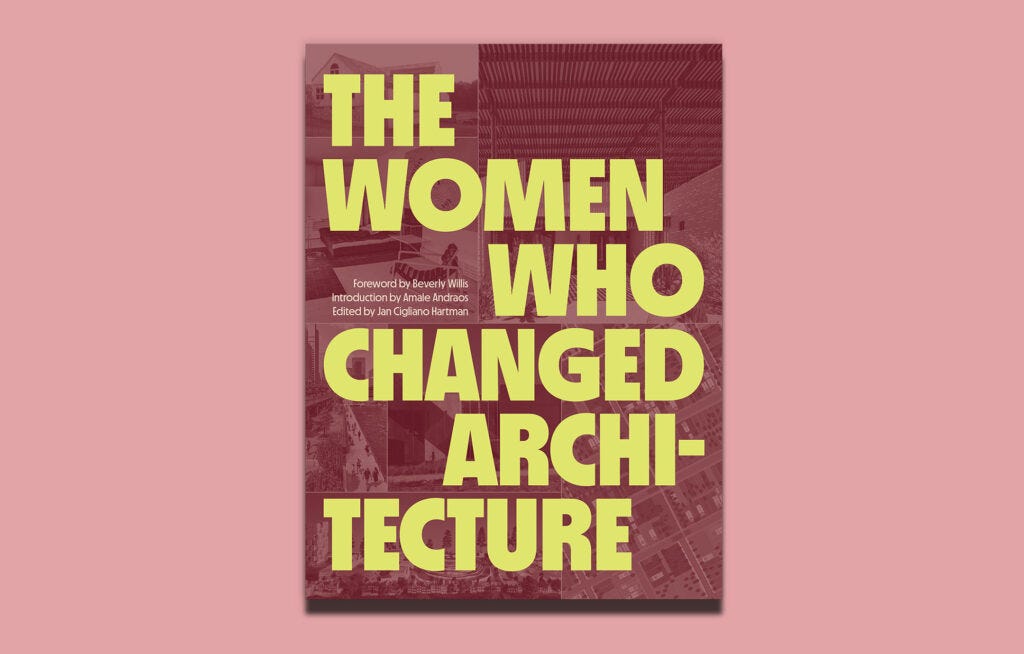

A new book celebrates six generation of women architects

In 1991, Denise Scott Brown pointedly did not attend the ceremony for the Pritzker Prize, arguably architecture’s top honor, which was being awarded to her business partner and husband Robert Venturi. The jury stuck to its rule about only awarding individual architects, causing a widespread outcry that resurfaced two decades later when Brown claimed, upon receiving another award, “Let’s salute the notion of joint creativity.” A group of young design students organized an online petition that received more than twenty thousand signatures, including those of nine other Pritzker winners. The foundation that oversees the Pritzker has not seen fit to amend its original decision.

This aspect of Brown’s professional story is retold in The Women Who Changed Architecture (Princeton Architectural Press), a hefty and attractively designed volume that presents short sketches of the lives and works of 122 women working in and around architecture. Brown’s titanic achievements, with and without Venturi, certainly changed the direction of the profession. She can be partially credited, too, with the changes wrought by the countless young designers drawn to the field by her creative work and her example. Yet the Pritzker snub represents why, despite great strides made in the field, a book like this remains necessary.

The lives and careers of the women featured here span nearly a century and a half and six loosely organized generations, which give the book its six-chapter structure. Editor and historian Jan Cigliano Hartman and architect Amale Andraos, together with a team of introductory essayists and thumbnail biographers, have compiled a volume that attempts to rectify two acts of under-representation. First, they aim to rewrite architectural history so that the contributions of women architects, designers, educators, and planners are acknowledged by name. Second, and less explicitly, by surfacing and celebrating these figures, Hartman and Andraos aim to do what Brown does by example: illuminate career paths for young people who identify as part of equity-seeking groups and are considering architecture. The Women Who Changed Architecture is an invitation—to rethink what you know and to rethink what’s possible in the field.

Simply by ascribing work to women by name does a great service. I’m a fan of architecture working in adjacent fields and, as such, am familiar with many of the twentieth- and twenty-first century projects included here. But the book taught me with embarrassing regularity how, even when I knew the name of the firm behind a building, I did not know who was primarily responsible for it. By surfacing the pioneering and talented women attached to well-known firms—from those who partnered with Frank Lloyd Wright a century ago to those co-founding active studios like WXY, MVRDV, and KPMB—The Women Who Changed Architecture broadened my appreciation of individual women’s achievements.

The Women Who Changed Architecture is not merely a who’s-who guidebook. It also, ambitiously, attempts to toggle between individual recognition and generational coherence, between biography and history.

But the book is not attempting mere hagiography; it’s not meant as a who’s-who guidebook. It also, ambitiously, attempts to toggle between individual recognition and generational coherence, between biography and history. In moving from one generation to the next, the book’s many authors are attempting to both define each cohort and suggest the progression from one to the next. Late-nineteenth-century “groundbreakers” enable early-twentieth-century figures to “pave new paths” by working at a variety of scales. After a mid-century lull marked by the Great Depression and World War II, a postwar generation “advanced the agenda” by “expand[ing] and redefin[ing]” architecture.

By the 1970s, in concert with a proliferating feminist movement that was “rocking the world,” women architects undercut the lone-genius stereotype to build “highly successful careers based on collaboration and flexibility.” By the fifth and sixth chapters, such overarching structures feel increasingly tenuous: as Julia Gamolina admits, about those “raising the roof” to “redefine what architecture is and can be”: “Writing the introduction to this group of women originally led to the thought that these women do not belong to the same group, or to any group at all.” And it’s true: the authors’ rhetorical and intellectual scaffolding feels more flimsy the closer it marches toward the present.

That’s the challenge of all historical writing, of course, and the stories of many of the profiled architects are still being written. But one of the book’s strengths, in its latter half, is the number of interview excerpts woven into the profiles. It’s delightful and instructive to hear Mabel O. Wilson say, “I felt like I was a vampire [at architecture school], like I was looking into this mirror, and I could not see myself.” Or to hear Meg Graham proclaim that, “Architecture is about designing both for the individual and for the collective, creating a kind of space that transcends the individual.”

These insights, alongside the broadening range of women featured in later chapters—educators, activists, and government officials alongside architects—hint at the breadth of the field today. The Women Who Changed Architecture will hopefully contribute to its further redefinition and expansion.