In the Mix

Osman Bari on magazine-making and honoring but not being constrained by identity

Designer and editor Osman Bari on making a magazine during the pandemic, honoring but not being constrained by identity, and on printing techniques as their own narratives.

BS: You have deliberately chosen not to attribute your issues to a particular year, season, or month. Can you talk about the sense of time at play in the magazine, and about making a magazine during the time-warping pandemic?

OB: Time is important to many of the stories in Chutney, especially the ones rooted in personal memories or in historical context. The very first story in the new issue provides an historical overview of marijuana and its influences on the South Asian subcontinent, then connects that past to contemporary issues such as legalization. Another story, about black cake, includes information about indentured servitude and the sugar trade in the Caribbean. Perhaps we can say that time works in the magazine through connecting one’s experiences to broader cultural and historical contexts.

As for the pandemic: the magazine did me a lot of good, kept me busy during long lockdown hours. I was working independently, so it gave me structure when there weren’t many other freelance-design opportunities. All told, I worked on the issue from December 2020 until about July 2021. The issue is, in that sense, rooted in the pandemic. But readers will get no more than a hint about when it was produced; I didn’t want it to surface prominently.

OB: Each section has its own function and definition, though they are loosely applied. Chop is about subverting stereotypes and stories that break convention. Mix is about cross-cultural influences and intersectionality. Preserve is about lesser-known histories and personal traditions.

Because individual issues aren’t themed, when I reach out to collaborators I use these sections as parameters. Of course, a story could cross from one section to another—in the end, of course, that’s what happens to a chutney.

BS: It appears, from the contributors list, that the community around the magazine has grown from the first to the second issue. Can you talk about how the Chutney community has begun to cohere?

OB: The first issue was, as with many new ventures, filled with people I know. I even contributed stories. This issue has fifteen distinct voices, each of which represents its own communities. One lesson I’ve learned is not to treat representation as a checklist, or treat people tokenistically. Individuals’ experiences are so much richer than community definitions grant them. Because of the magazine’s name and my own cultural heritage, it has connected with many people from Pakistan, or from the subcontinent in general. But it’s important to be clear that the magazine is not about one particular place or community.

BS: Has the magazine’s reception borne out that hope?

OB: Readers have generally understood that Chutney isn’t about national, or ethnic, representation. They know it offers, say, a taste of something—as well as an opportunity to better understand people who hold different perspectives. Whether you see yourself in another’s story or simply appreciate it because it’s presented with nuance, the focus on individual experience, I hope, enables truer connections with readers.

BS: The current issue was produced while you were living in Toronto. Last autumn you moved to London, the “heart of the empire,” as you have called it. Can you talk about how that move has changed your impression of this issue and your process for making the next?

OB: I felt like I was going into the belly of the beast, so to speak. As someone from a colonized country, British culture was always in the background (when it wasn’t foregrounded). I feel a connection to it; it’s a relevant part of my own cultural history. Being here, though, makes the just-completed issue feel more “Canadian”; I have begun to feel more firmly that it’s rooted not only in the time of the pandemic but also in the place it was made. Because I was living on that land at the time, it wasn’t as apparent.

When I refer to “so-called Canada,” people living there tend to get it; we share an understanding of the complex histories of that place. That requires additional communication now that I’m living outside the country, not least to explain that the magazine is not “Canadian” in the sense of ice hockey, maple trees, and national identity.

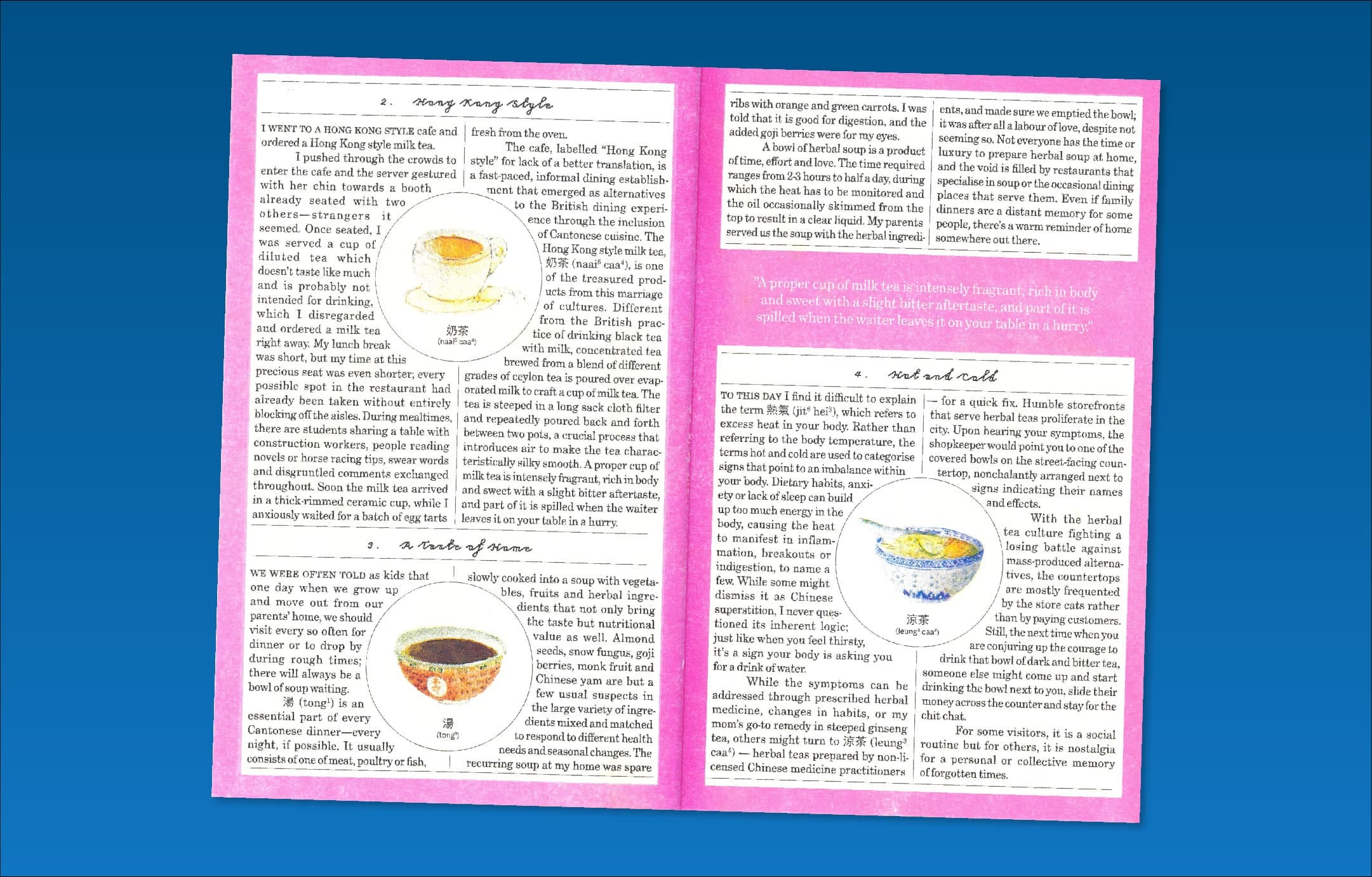

BS: The magazine is printed on a Risograph machine and features more illustrations, paintings, and drawings than photographs. Can you talk about tactility, the hand, and perhaps how that relates to ways knowledge is transferred?

OB: The magazine’s tactility is in part a product of the pandemic, when I wanted something physical to hold, a vessel for carrying stories in a time when everyone is distanced. The thermography on the cover is an additional layer of texture. Risograph ink comes off on your fingers. And by adding fold-outs and inserts I made progressing through the magazine a kind of narrative itself.

I’m also, simply put, a believer in the beauty of print. It’s especially nice to hold something other than your phone. The magazine might be more accessible digitally, but it wouldn’t work the same way, it wouldn’t communicate as much about the people who contribute.