Lifetime Supply

On securing the words and pictures that mean most to us

Hi everyone,

I’ve unlocked last Friday’s Supporter Update, which includes links to great new stories, podcasts, and videos related to our recent issues, plus a recommendation of one of my favorite artist-filmmakers working today.

This week’s letter is about the frailty of our digital files. The majority of our communication and, for many of us, the majority of our work now takes place on computers, tablets, and phones. Six weeks ago, I wrote about the emotional landscape hidden in our most-used apps. How do we make sure that landscape doesn’t dry up?

I’d love to know what you’re doing, if anything, to safeguard your digital life. Do you trust cloud backups? Are you doing something more? Reply and let me know, and I’ll compile answers for a future issue. Read on to find out why I’m asking and discover recent stories—and a surprising product—on this theme, plus an iOS camera-app recommendation and a fistful of good links.

Love all ways,

Brian

Lifetime Supply

When my parents visited this summer, my mother brought a stack of drugstore-print photos from my childhood. There I was, in a soccer uniform, circa 1986; sitting at a boxy desktop computer, my bedroom walls a mosaic of taped-up punk-show flyers, circa 1994; visiting from New York for my grandmother’s ninety-fifth birthday in the mid-2000s. The photos resurfaced memories and emotions I hadn’t experienced in years. Stashing them in the box with grade-school report cards and letters from teenage pen pals would likely consign them to another decade out of mind. And since I’m purposely changing how I use my digital devices to foster serendipity and emotional resonance, I began to think about how I should digitize them—and, in doing so, to come across essays and even products that grapple with similar questions.

Sure, I could scan them and add them to Apple’s Photos app, where I currently have eight thousand pictures. But the prints my mother brought had already survived as long as three and a half decades. Would only storing them in that software ensure similar longevity? People in technology have often espoused a phenomenon known as the Lindy effect. It states that for certain things—like file formats and software programs—the longer something has survived to exist and be used in the present, the longer its life expectancy. In my example, should I trust the longevity of JPEGs, which were developed thirty years ago and can be read by every digital device, or HEIFs, which Apple officially adopted in 2017 and which, as of last year, no web browser officially supports?

If I did put them only in Apple Photos, can I trust its iCloud service? In this limited use case, as the meme has it, the cloud is just other people’s computers. And as Jonathan Zittrain memorably put it in 2021, “the internet is rotting.” Two months ago, Casey Cripe expanded on this theme, writing, “Without constant maintenance and management, most digital information will be lost in just a few decades. Our modern records are far from permanent.”

This fact has been repeatedly brought home to me when I’ve looked for copies of reviews, essays, and even Livejournal blog posts from the outset of my career—and instead found dead links and 404 Not Found pages. The Wayback Machine helps (here’s a blog I wrote in 2004–2005), but it’s imperfect and the nonprofit that runs it is beset with legal challenges. Apple has the world’s largest market capitalization, so momentum and its bank accounts will likely carry it into the twenty-fifth century. But will my pictures tag along for that ride?

Two weeks ago, Wordpress, the website-building platform behind nearly half of the web, announced a cheeky new product meant to solve precisely this dilemma. For a one-time fee of $38,000 USD, its 100-Year Plan “ensures that your stories, achievements, and memories are preserved for generations to come.” I admire CEO Matt Mullenweg and Wordpress likely has the momentum to last that long as an organization. But despite promising “the ultimate in security and longevity,” it’s hard to picture a Wordpress software engineer, seventy-eight years from now, trying to revive a dormant third-party plugin so you can retrieve videos of your kid’s soccer game.

Earlier this summer, while all this was top of mind, Stephan Ango, CEO of the software company Obsidian, posted a pithy essay called “File over app.” It concisely explains the stance I adopted about five years ago. “If you want to create digital artifacts that last, they must be files you can control, in formats that are easy to retrieve and read. Use tools that give you this freedom.” I’d gone looking for my old writing in recent years because I wanted to store copies on my computer as plain-text files. With the Lindy effect in mind, I presume that if those essays can be read by a computer from the 1960s, a computer in the 2080s—whatever form it takes—should have no trouble displaying them.

I do this personal archiving not because I presume what I’ve written is of broad significance. But I was delighted to receive my childhood photographs and am always happy to be reintroduced to the person I once was through my old writing. I expect the same will be true for my two young sons when they are adults—at least for their soccer photos, if not for the exhibition reviews I published in my twenties. Here’s Ango, the Obsidian CEO: “It’s the plain text files I create that are designed to last. Who knows if anyone will want to read them besides me, but future me is enough of an audience to make it worthwhile.” Six weeks later, he made the point again when sharing a small, privately printed book of remembrances by his great-grandfather.

So I’m scanning the photos my mother brought and saving them as JPEGs in several locations—including, yes, in Apple Photos. But for now, I’m keeping the originals in a box in the closet, too.

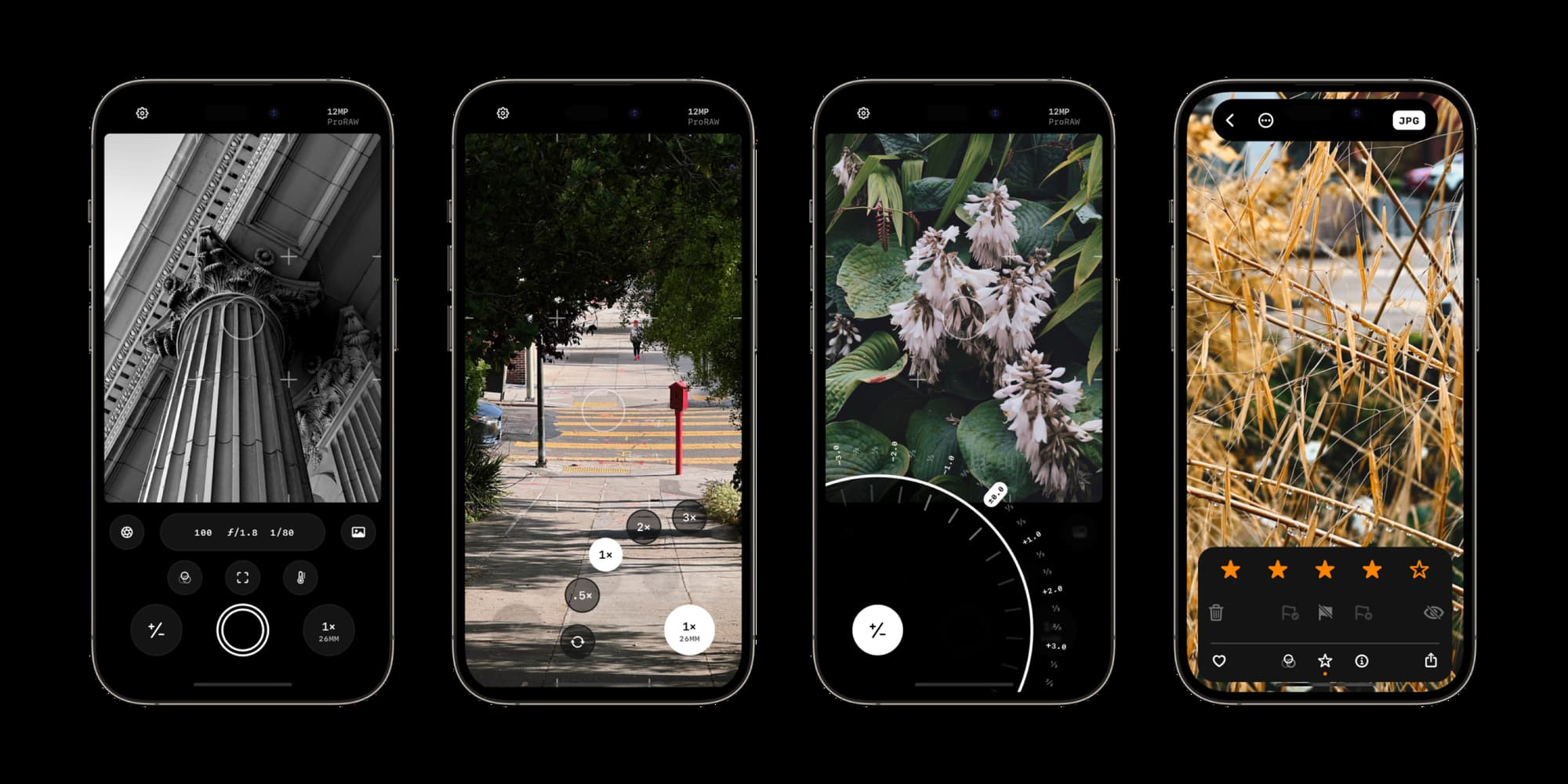

App Recommendation: Obscura 4

Speaking of photos: the independent developer Ben Rice McCarthy recently released a major update to Obscura, his iOS camera app “built for pros, designed for everyone.” I’ve been enjoying it this past week and think it’s a great option for anyone eager to have more control over the pictures they take or wary of the sometimes extreme image post-processing in Apple’s default camera app.

Halide is a popular option for this kind of photography, but I’ve never managed to become comfortable with its details. Obscura is as powerful and its interface has proven much more legible to me. Plus, unlike Halide, it lets you record video, apply filters, and change the camera’s aspect ratio. If you’re taking more than snapshots, check out its website or this Macstories rundown.

Good Links

- 🏢 The wonderful New York Review of Architecture has an attractive and expansive new website

- 🔋 “What differentiates these experiences isn’t the number of hours in the day but the energy we get from the work. Energy makes time.” –Mandy Brown

- ⌛ “Leisure requires cultivation—cultivation of habits and of communities that help to form habits.” –philosopher Zena Hitz asking “What Is Time For?”

- 🔠 “The Revitalizing Power of Indigenous Typography” (yes, yes, the irony of this emoji …)

- 🌏 Art historian Matthew Israel asks, “How Should the Art World Respond to the Climate Crisis?”