Longform Editions on running a record label like an art gallery

Cofounders Andrew Khedoori and Mark Gowing on their egalitarian ethos, emotional sustainability, and the value of curatorial vision in an algorithmic world

Episode Transcript

Andrew Khedoori: We knew we weren’t going to be in favor with the algorithms at play. But it was part of this operation to just have a great series of music and not think of any of those considerations whatsoever and just find the audience.

Mark Gowing: Everyone else who’s not letting the robot serve them.

AK: I’ve discovered fantastic things on Bandcamp. I’ve discovered great things on radio. That curatorial point of view is still very important to me.

I still think that holds value for a lot of people. We just wanted to put out great music. And if we’ve given ourselves that opportunity not to worry about those other things, then that’s fine.

MG: We believe in choice and we believe in curation and choosing the kind of art you need to hear or see.

AK: You’ve got to commit to Longform Editions. That’s the whole point of it. If you want to get something out of it, you have to give it your time.

Brian Sholis: I’m Brian Sholis, and this is the Frontier Magazine Podcast, where I interview artists, writers, technologists, architects, and other creative people about their work and the ideas and ideals that inspire it.

Today I’m speaking with Andrew Khedoori and Mark Gowing of Longform Editions, a “curatorial music practice” based in Sydney, Australia. Both longtime participants in Australia’s independent-music community, they collaborated for more than fifteen years on a record label called Preservation before launching Longform Editions in 2018. As the language suggests, a “curatorial music practice” is distinct from a record label. I’ve admired how Andrew, who works in community radio, and Mark, who is an artist and designer, are rethinking the conventions of releasing music. They’re doing so in order to give artists creative freedom and ensure they can sustain the project for a long time. Longform Editions has released music by some of the finest experimental musicians working today, from Caterina Barbieri and Carmen Villain to Sam Prekop and Chuck Johnson. Several of its 2023 releases, including those by Cole Pulice and Melanie Velarde, are sure to be on my year-end favorites list. And with four new pieces of music every two months, the back catalog includes a ton of mind-expanding work from under-recognized artists as well.

You can learn more about Frontier Magazine and subscribe at magazine.frontier.is. Thanks for listening. And now, my conversation with Andrew Khedoori and Mark Gowing of Longform Editions.

BS: So it’s been a little more than five years since you launched, but I want to ask you both about your backgrounds and how you came to work together.

MG: I’ve been working as a designer for about thirty-five years. And these days I work exclusively as an artist and a typographer. Andrew and I started working together because we were both working in the music industry in different ways through the 1990s. I worked in magazines and then I worked for record labels designing covers, as you do, and got quite disgruntled. And Andrew was working as a label manager and A&R and all those kinds of things. And then we met along the way and he got disgruntled, too. So we started a label. What would your version of that be, Andrew?

AK: I was working at a radio station for a really long time. Mark and I became friends through the indie band scene in Sydney. When you all go and see the same bands, eventually you come together. And a lot of what we have done together professionally is still really wedded within that friendship. We have certain ideals. Mark and I basically sit on the same page when it comes to our creative endeavors, but we both come to that page from very different angles. We’ve been able to complement each other in good ways for a really long time. But yeah, Mark was a graphic designer. He was working at Rolling Stone. I was a contributor to Rolling Stone for a period and also the music director at a community radio station here in Sydney called 2SER, which is kind of like a cross between your public radio and your college radio.

I think we started both to have a burgeoning interest in more electronic and experimental music that was starting to creep into the indie vernacular. Certainly with artists like Tortoise and Labradford and so forth. And at the same time, I was really getting interested in design through Mark.

Then this opportunity came along to release a record. My friend Oren Ambarchi was working on a pop record and found it a little bit difficult to find someone to put it out—whereas previously, because of his reputation in the experimental world, he had no difficulty finding a release option. And he suggested that I start a label, and I thought, well, you know, it’d be good to do this with Mark. And we started [Preservation] probably in somewhat clunky fashion, but we were learning and we were enthusiastic. After quite a long time running this label, we both worked on this idea of Longform Editions.

MG: Preservation has kind of come to its natural end. We were kind of finished, I think, and we kind of petered out. And then a year or so went by and then Andrew called me up one Saturday morning and said, I’ve got an idea.

And out of the birth of that idea came Longform Editions. We didn’t act quickly. We had seventeen years’ experience or something and we were able to sit down and calmly plan this thing out. We didn’t want to create something that would burn out and that would prevent us from continuing to grow and learn. So it was really centered around making something perpetual and valuable to us, rather than a business that would make money or, I don’t know, those sorts of normal things that a lot of people reach for when they start a company. I guess we didn’t really start a company.

We just put out four things and hope that they’re valuable. We hope that they’re good to listen to and they offer something and we’re contributing to the music culture that we love very much.

AK: If you are running a label in a very traditional sense, there’s no shade on that. But we just found that those industry trappings that a lot of people battle through were just starting to weigh upon us. We looked at all the various things that we felt were stopping us from doing the things that we originally bought in with, and we tried to make Longform Editions bulletproof from things.

So while we really believe in the concept of Longform Editions, we also knew that as a by-product of releasing things digital-only, we weren’t going to have to sink a ton of money and rely on third parties to deliver vinyl or CDs or cassettes or whatever. We could just do this all ourselves and our main relationships would be with ourselves and the artists. And we also thought, well, you know, we’re not going to enter that rat race where we’re looking for radio play or things like that. We just put out four things and we hope that they’re valuable, we hope that they’re good to listen to and they offer something and we’re still contributing to the music culture that we love very much.

BS: I’m listening to you describe yourself as running a label, but, you know, the phrase record label is the conventional way to describe what you do. But you’re not releasing records, and you don’t necessarily have a roster of artists that you work with repeatedly, you know, the way that a typical label would. And instead, in the way that you describe yourselves is, well … you make reference to art galleries.

MG: That was something that I brought up with Andrew really early on, maybe even the first conversation that we ever had about Longform Editions.

I wanted to have an entity that treated artists as artists, rather than as entertainers. If you treat music as an art form, as a true art form, say, then what do we need? We don’t need a label to sell it. We need an art gallery to show it. We can just let all of those financial problems and those sales problems go and just say, “Okay, we’re going to behave like a gallery.” And that quickly governed the idea that every two months we have a group show of four artists and we show that work. We changed our mindset from releasing to showing.

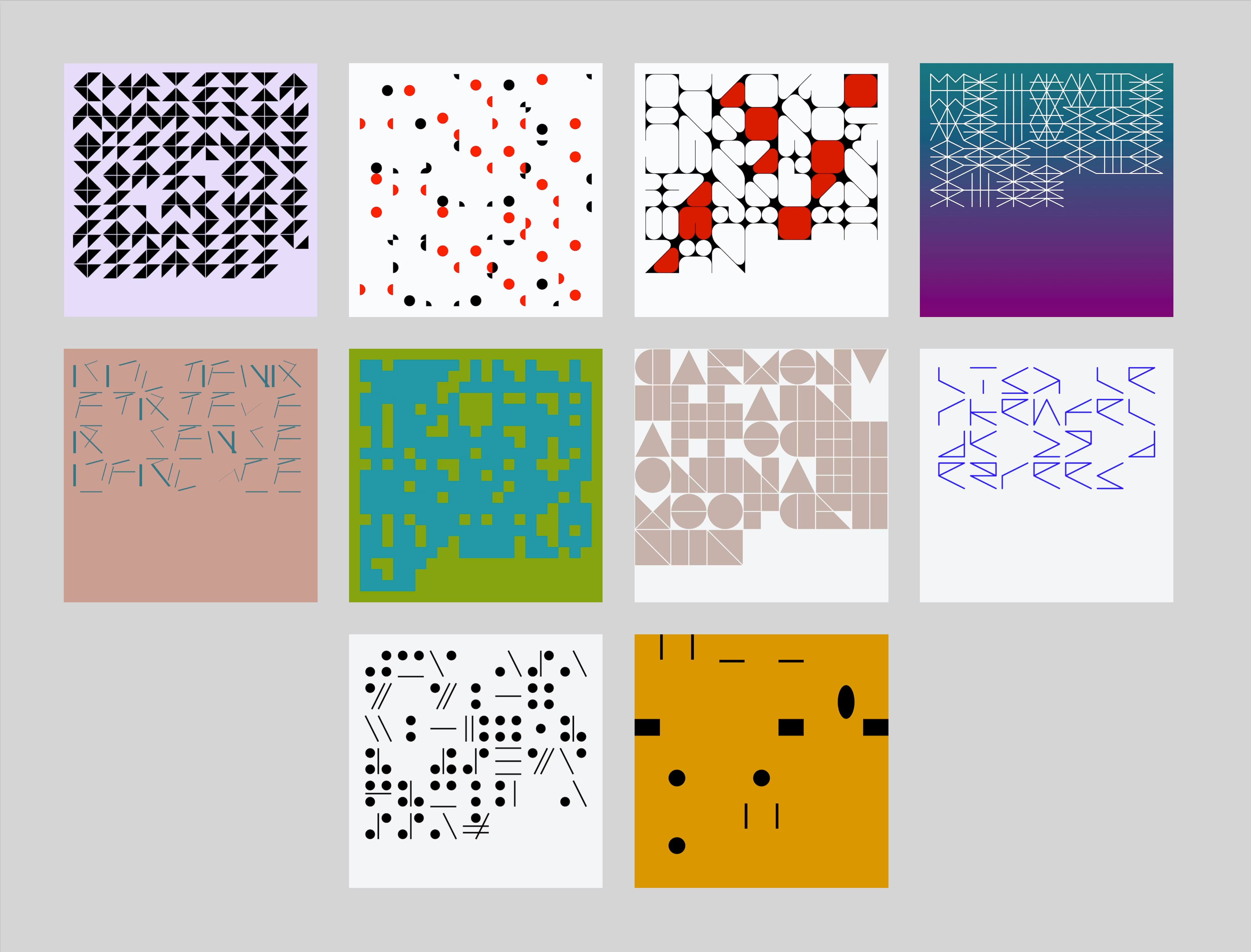

BS: I’d like to linger with you for a moment, Mark, because the design of Longform Editions encourages a kind of … we’ll call it loose coherence, a sense of it being a group show. If I understand the gestation correctly, there was a series within Preservation’s output called Circa and that had a coherent design sense. And now, Longform is a series-based design rooted in experimental typography and your typographic practice. And I wonder if you can talk about how those typefaces are generated, why it is that that’s how you chose to create this roughly uniform presentation of very disparate artists’ work, and what that does also to set Longform Editions apart in an experimental music landscape where everything is seen on people’s screens and in two-inch squares.

MG: Circa was absolutely the precursor to Longform Editions. Andrew invented Circa along the way. And it was a similar idea. It was called Circa because there was about that moment in time when all of that stuff happened. It was about timing. And Longform Editions is about really similar things. The few things that set of decision-making did for the design—like the idea that it’s digital only; it’s an art gallery, not a label; they’re pieces, not tracks—all of that change in thinking leads you to this point.

One of the first ideas about Longform Editions was that it should be egalitarian. It shouldn’t be one recording, let’s say, that gets more attention than another. Shouldn’t be like, “Oh, we’ve got this artist now, so we’re going to pour ourselves into that,” which happens when you’re running a record label. You have four records on the table and one of them is inevitably going to get a lot more money and attention, a lot more investment than the rest. And we decided that wasn’t going to be the case. So it was about everything being equal, all the artists being equal, all the recordings being equal.

And then as well, it was about that idea of streaming and no matter what platform you’re on, there doesn’t need to be any legible type on that square that represents the cover because there’s always a title beneath it. And that simple thing about digital streaming just removes a whole suite of problems from the equation. So it means that square becomes a completely abstract idea and anything can happen in it. It’s no longer about communicating anything exact. So that frees you up. So I took those covers as an experimental space. I have a typographic practice that has been evolving over a lot of years and it has evolved into that space and I don’t try to stop it. I don’t try to control it and make it more palatable for business. I just roll with it and see how far it can go. It just seemed inevitable for me, like to just use it for Longform Editions. What else would I do?

AK: We release twenty-four things a year and I’m not going to ask Mark to do twenty-four highly individual covers in the traditional sense. You know, I was about to say that would kill him and we probably wouldn’t be doing this. But we have arrived, I think, at the best of both worlds where we can continue our momentum. And I think that releasing four things every two months allows for that momentum. And I think that we need that visual component to signify that as much as what the music signifies as well. Every time we release a new typeface, the feeling for it is great. People love it. They get really excited about seeing what’s next, you know?

MG: But I mean, that thing you said about practicalities, that’s been a driver behind a lot of what we do. Keeping a measure on our time and our energies, because we did pour so much into the old label and it got out of hand a lot. Now we just have systems in place.

And the design is a part of that, but there’s other things, too. Every six months, there’s work involved in creating a system, but that’s it. So it’s about that effort management, you know, that keeps you in the game and it keeps you fresh.

We didn’t realize as younger people how important that was. Now we know all too well that we have to really manage our efforts and make sure that we’re still passionate and that we still have time left to concentrate on other things when we need it rather than just being burnt-out all the time and overworked.

AK: Structure is really important to us.

BS: I would like to talk with you briefly about that invitation that you do extend to artists, because it’s my understanding that it’s incredibly open-ended. When you are approaching an artist, can you tell us what exactly is the offer or the request? And if indeed it is open-ended, which I think it is, how has that led to results that have surprised you?

AK: One of the reasons why we decided to go with long-form pieces is we wanted something that was individually ours, but we knew that in the face of our cluttered digital space or our cluttered lives and just the barrage of things coming to us, our attention spans were just dying. And we wanted to create a space where you could reclaim that space and create music works that would allow that. Just like when you go to an art gallery and you have a sense of stillness and it’s a rarefied space. You can spend as much time with a piece of work as you want to. We wanted to put that in this digital space and also allow you to travel with it. Put your earbuds on and off you go. Music’s the most malleable art form, really. So that’s what we kind of wanted to get the best of both worlds there.

Longform Editions is a space of exploration. We’re not looking for perfect works, and you can really hear how people really understand they have a big canvas to work with.

Five years ago, I would introduce myself to people and I’d say this is the idea of the project, would you like to take part? And there were some really great early adopters who were very enthusiastic. Then we started releasing things and getting a little bit of traction. A lot of the time when I approach people, they seem to be already aware of it. So they know that if they’re gonna come to the party, they’re gonna bring a concept and produce something pretty special. Look, it’s really variable. I’ve had a piece arrive in nine days. I’ve had a piece last year come in after several years of waiting, so it just varies. It’s quite organic. I think once the artist realizes that you’re a passionate human being corresponding about shared love for music and what the possibilities are, it’s actually really exciting. It gets into this heightened space where you’re just having these great conversations. It’s really nice to be a part of that. It’s really quite a privilege actually.

MG: But then there’s been a couple of moments where we’ve been sent things and Andrew forwards them to me and says, “Can you have a listen to this?” I don’t know. It’s that great moment when somebody does something that’s truly groundbreaking. It’s hard to recognize for a minute, you know, even as people who hear this stuff all the time. We both listen to it and start talking about it. And we’re like, “This is something else.” You just kind of go, “I don’t know, what is this? Oh my God, what is this? I don’t know. What—is this good? Is this not good? What is it?” And then you kind of settle down and go, okay, this is incredible. Because it is so original. It’s an incredible thing that in the moment, in the first few minutes of hearing it; it’s hard to recognize sometimes.

AK: Longform Editions is a space of exploration. We’re not looking for perfect works, but you can really hear how people really approach the fact that it’s open-ended and they have a big expanse or big canvas, if you like, to work with.

BS: It sounds to me like there’s a little bit of a tension or a paradox that’s emerging in some of your answers that I want to tease out a little bit, which is that the way that you’ve structured this project could only have happened with the advent of digital distribution. And there are advantages to that. You lose all the costs of shipping, lose all the material costs, it’s better for the environment. There are design advantages, you know, in the sense that the metadata is right there in the app with whoever’s listening to it.

But I think at the same time, you also made mention about our atomized or shortened attention spans. And I think that there is something about that that could be laid at the feet of digital technologies. And so I’d like to ask you a little bit about, I guess, algorithmic discovery. And there’s an American journalist named Kyle Chayka who’s written quite a lot about how algorithmic discovery shapes how many people, if not most, now experience culture. I wonder if you can just talk about individual and curatorial exploration of the type that you’re doing to put out this music over and against that idea of algorithmic discovery and the way that most people sort of lean back and let culture wash over them today.

AK: First of all, you can find all the Longform Editions work on streaming services. And we had quite a debate about streaming services. And I was actually against it. Mark was for it.

But we kind of approached it with a Trojan horse mentality, just hoping that if people were interested in experimental music or electronic music or whatever, or a particular artist, they might sort of stumble across us there and it was an avenue. We will always want Longform Editions to be accessible. The price point is accessible if you feel like it has that value, but if you don’t want to pay for it, but you still want to be engaged with it, you have that opportunity.

I think that egalitarian point of view for our operation that Mark mentioned is important from the audience point of view as well. We knew we weren’t going to be in favor with the algorithms at play. But it was part of this operation to just have a great series of music and not think of any of those considerations whatsoever and just find the audience.

MG: Everyone else who’s not letting the robot serve them.

AK: I’ve discovered fantastic things on Bandcamp. I’ve discovered great things on radio. That curatorial point of view is still very important to me.

I still think that holds value for a lot of people. We just wanted to put out great music. And if we’ve given ourselves that opportunity not to worry about those other things, then that’s fine.

MG: We believe in choice and we believe in curation and choosing the kind of art you need to hear or see.

AK: You’ve got to commit to Longform Editions. That’s the whole point of it. If you want to get something out of it, you have to give it your time.

BS: Algorithms not only structure how many people experience culture, but also what kinds of culture get produced. Let’s say that the potential windfall of the algorithm embracing your music can lead people to cater to it. The hook appears earlier in the song these days, or the chorus comes up sooner, or the overall song gets shorter. So I take what you say about this being not a deliberate reaction, but is instead a choice to focus on attentive listening—deep listening, to use a term that’s kind of a cliché in this corner of the musical landscape.

MG: I’m thinking that the algorithmic problems are not that different to radio, when radio was the chief output. If you wanted to get a song on radio in the 1980s, the songs were short. They were sharp. They were, you know, crazy hooky. Whether they be radio, whether they be MTV, you know, those problems have been repeated for decades. The short song that fits on a vinyl single, but also fits on radio. The album was about how many radio-length singles would fit on an LP. And then that got translated into CD and so on. And now it’s still embraced in digital music. And yet everything about digital music allows us to ignore it.

We no longer have to deal with either of those old formats—the single, the album. They’re all redundant. And Longform Edition was founded on that ideal. Andrew and I had this crazy conversation for hours one morning, going, “This stuff is all redundant, it’s dead.” And yet we continue to service it. Everybody continues to service these dead ideas. And so we cut it loose. We intentionally went, “Okay, we’re going to make a format that doesn’t pander to any of that pre-existing stuff. That doesn’t fit.” You can’t fall back into your habits of making a single-length track. You can’t make an album. You don’t have to write eight pieces. You can just make one beautiful piece. You can just release music.

I’ll just want to add that the incredible thing is that Longform Editions has garnered some good notice in the media. But it’s about Longform Editions. They can’t do reviews because Longform Editions pieces, to them, it’s not a single. And they know it’s not an album. Longform Editions stumps them.

BS: I take every single one of those points. And yet, there’s a surprisingly high number of Longform Editions releases that come in at like twenty-two minutes and seven seconds, which is one half of an LP. So there’s something about these formats that have an afterlife in our imagination. Even when you have no boundary given to you by the person who’s going to be releasing your music, you still find yourself … there’s something about it that’s comforting, comfortable, familiar. It’s just a natural form of expression.

AK: I haven’t noticed the twenty-two-and-a-half minute scenario myself. But look, the music industry and the associated media that goes with it is still very much format-driven. They’re very slow in turning around to new ideas about music because the media that surrounds it needs advertising dollars to survive and sustain itself. So, you know, if the music industry is still by and large pandering to the formats that were created in the 1950s, that’s what you’ll do.

MG: All that said, there is something in-built in us about timing and digestion. And I’m still a massive fan of the three-minute pop song. I think it’s a wonderful art form, but it’s just not what we do.

BS: We’ve talked this long without addressing the biggest news in the field of independent music this week. And for context, a few weeks ago, the gaming company Epic sold the music-distribution platform Bandcamp that you all use to another music tech company called SongTradr. And there was a little bit of a pause after that happened. You could say maybe people were holding their breath. But now we know that more than half of Bandcamp staff was fired. And since you rely on Bandcamp for sales and distribution, and since distributing and getting attention for independent music or experimental music is already something of a challenge, maybe I’ll ask first: how are you doing? And then also, what do you think this might mean for the broader independent music landscape?

AK: Look, I know that the American indie scene that I follow, they’re all in mourning and it doesn’t sound like great news. But I kind of want to step back from the hand-wringing for a little bit and just wonder, what could they do with it?

I mean, essentially Bandcamp is a platform where anyone can upload music for the purposes of [getting] somebody to listen to it and potentially buy it. Where can you go from there to really stuff that up? I think that if there were cost-cutting measures that needed to take place, I can’t answer to that. I know that people were really concerned that the editorial team had been cut in half. That core function of just a platform where you can upload without barriers: I’m hoping that remains. I’ll be fascinated if they keep Bandcamp Fridays, which waives the Bandcamp fee because that, I would assume, hemorrhages a lot of cash.

MG: It’s a big day for us and we’re not big.

AK: I’m going to go out on a limb here: I wouldn’t mind if Bandcamp Fridays went [away] because what I find is that you have a glut of releases and everybody’s vying for your attention on Bandcamp Friday. And I think that a lot of people think that they’re doing the right thing by waiting till Bandcamp Friday. And inevitably there’s a deluge and people miss out. I’d like it to level out a bit more and have people buying regularly on Bandcamp because we find that sometimes, in between Bandcamp Fridays, is a little quiet.

MG: But I mean, for us, I think Bandcamp’s always been really, really good to us. They’ve kind of gone out of their way to find a place for us. After a couple of years, they kind of noticed us and were like, “How can we help?”

And it’s been really lovely. They’ve been really warm and helpful. But the worry for us has always been that the technology was aging poorly. We were kind of hopeful when Epic bought in that Epic would invest technology in it, being a technology company. And they didn’t. And now it’s been purchased by someone who’s not really a technology company. I think the biggest worry, it seems that they’re going to kind of maybe let that end of it rot somewhat. Um, I mean, I hope that’s not the case, but by laying off curatorial and technological staff, it’s not a good sign.

AK: Somebody quite rightly pointed out on Twitter, the reason that a music magazine like The Wire, which concentrates on some of the most obscure experimental sounds around, the reason why it’s been going for so long is that the seven staff members who run it, own it. They bought it out. And it’s an incredibly valuable space. It’s because it’s run by those people who are passionate about the things that they write about.

Look, you know, I’d like to hope for the best. I think Mark’s concerns are really valid. I think all the concerns and essays that have been out over the past week hit the nail on the head. But I just kind of want to kind of go, “Okay, let’s just now, we’ve speculated, let’s see where this goes now.” And I’ll hope that there’s still that basic functionality of being able to sell your music on a platform that doesn’t have a lot of barriers.

BS: I appreciate that optimism. Maybe we can end with a final question that allows us to give evidence of a curatorial sensibility, the kind that we’ve been discussing, as well as to share our enthusiasms. So maybe we can go back and forth for one or two rounds here and recommend other labels. For someone who’s listened to this podcast and discovers Longform Editions for the first time and is really excited, where else might they look next? I’ll start because I have in mind an Australian label, and I’ll just keep shining attention down south. I love Room 40, which is also based there and run by the wonderful musician Lawrence English. What might you suggest for someone who’s just discovering this corner of the musical landscape?

AK: Mondoj from Poland is a really fantastic label. The label Orange Milk is always releasing really interesting music as well. Moon Glyph is a label run by Steve who was Omni Gardens and on Longform Editions a few years ago. I’m really loving how Moon Glyph is evolving. Always major, major props to RVNG in New York. I think Matt Werth is one of the most open-hearted and amazing curators. I also really love Three Lobed, um, always continuing to find new realms for that kind of Dustbowl Americana, extended John Fahey sort of feel. I’m just trying to think of some labels here like Splitrec, which is a really tiny, tiny label, but basically accessible on Bandcamp.

Also, I’d probably be remiss if I didn’t mention Oren Ambarchi’s Black Truffle. Oren has some of the craziest but broadest taste of anyone I’ve ever known. I’ve known Oren for a really long time and I just have these memories of him. I was sitting in his bedroom when I was sixteen years of age. I’d say, “I’ve got to get the bus, it’s the last bus.” He’d say, “I’ll drive you home if you listen to side two of this,” you know. But yeah, he’s been running Black Truffle now for just over ten years. And he excavates some of the great old music that not a lot of people know about and really brings it to a fresh set of ears. And I think that that’s fantastic. Shelter Press is another label that I think is always releasing interesting music. There’s a lot, Brian. I’m glad I was able to remember some of them.

BS: What’s wonderful about that list is I’m a nerdy enthusiast of this kind of music as well, but no matter how much time I spend exploring this kind of music, on that list I probably only recognize two-thirds of the labels that you mentioned. And you mentioned a label in Paris and a label in New York and a label in Australia and a label in Poland.

It’s a small world, but it’s a world. And I appreciate what you all have contributed to it in the form of 130-plus releases, including four new ones just this week. And I’m also grateful to both of you for your time in this conversation. Thank you both so much.

AK: The pleasure is ours and thank you.

Thanks for listening to this episode of the Frontier Magazine podcast. It’s the audio component of our weekly publication, which features appreciations from the forefronts of architecture, technology, culture, and education. Each issue shares new ideas about how design and creativity accelerate positive change. Everything we publish is available for free; browse the archive and sign up for new issues at magazine.frontier.is. If you liked this episode, please share it with people you know and rate us to help others discover what we’re doing.

The magazine and podcast are products of Frontier, a design office in Toronto. Here’s studio founder Paddy Harrington:

Frontier is a design office. We believe in the expansive potential of storytelling to help people navigate the unknown to get somewhere new. We’re coming up on a decade of designing big stories in the form of strategies, brand identities, editorial products, and digital and real-world experiences that help organizations, brands, and individuals stand out and discover new creative territory. Learn more at frontier.is.

Thanks again. I hope you’ll join us for the next episode.