Palaces of the People

Museums are just people, lined up across the generations

Hi everyone,

I worked in an art museum before I regularly set foot in them. Though I had not taken Art History 101, a college advisor pointed me toward a semester-long internship at a nearby contemporary-art museum, where I helped write wall labels and grant applications, opened envelopes and boxes stuffed with hopeful artists’ slide sheets, booted up video projectors and DVD players, and tried to solicit free beer for an opening and a free hotel room for Yoko Ono. I was suddenly in a strange world full of earnest people trying to do surprising things with not enough money, all on behalf of artists I’d never heard of. It reminded me, in some obscure way I only recognized later, of putting on punk-rock shows. I got hooked.

So I moved to New York, found another internship, worked in a commercial gallery, began writing for art magazines. I became fluent in the languages of contemporary art, but also realized that most everyone around me had a much better grasp of art’s past. The further back in time the conversation went, the spottier my knowledge became—and the more idiosyncratic my tastes and preferences. I didn’t want to lose my taste, but I decided I should teach myself why I felt the way I did.

With an entry-level salary and two roommates in Queens, I wasn’t about to sign up for university courses, and YouTube and podcasts had not yet been invented. So I did what generations of aspiring young people before me did: I rode the subway uptown, walked in to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, paid what I wished (usually a few dollars), and wandered. I believed the strength of this habit would make up for what my plan lacked in structure. Visit by visit, artwork label by artwork label, I slowly became the kind of person who could distinguish between Courbet and Corot, or could talk about Lucas Cranach the Elder as a Protestant propagandist.

In this way, I was close to the ideal visitor envisioned by the Met’s founders in the 1870s, whose emphasis on education and uplift permeates Why the Museum Matters (Yale; buy via Bookshop or Indigo), a short treatise by the museum’s current CEO, Daniel H. Weiss. For well-to-do and well-intentioned nineteenth-century New Yorkers, as well as their peers in cities like Boston, Buffalo, Cincinnati, and Chicago, “The goal was to create spaces that served the larger public, providing access to education, beauty and cultural enrichment.”

This characterization of American art institutions comes after opening chapters devoted to the pre-history, in ancient Greece and Rome, and history, in Europe during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, of the “museum idea.” It’s a useful preamble, though I wish Weiss had spent less time on it and more time discussing the contradictions built into the liberal, reform-minded American museum founders’ premises. Why, for example, was there a decades-long debate about whether the Met should open on Sundays, the one day those “practical and laborious people” had off from their jobs? Such details, explored in other books, would have helped better situate the all-too-human conflicts and incongruities that characterize museums like the Met today.

After a brief chapter on museum buildings, Weiss turns from his history to the issues facing museums today, with brief descriptions of recent controversies over representation, as when protests erupted over the inclusion of a painting depicting Emmitt Till in his casket in the 2017 Whitney Biennial, and restitution, including tussles over the return of the Elgin Marbles to Greece and the Benin Bronzes to Nigeria. While acknowledging that these are complicated issues, almost immediately, I began placing skeptical question marks and surprised exclamation marks in the margins. I penciled quotation marks around the repeated phrase “To be sure,” which in each context became a soft condescension toward the people and ideas pushing museums to more quickly live up to their founding missions. Though generally even-tempered, I felt myself radicalizing page by page.

Weiss posits himself as a liberal-minded reformer gently pumping the brakes on those calling for substantive change. Sometimes he does so in a patronizing tone, responding to one critic by writing, “Of course, [doing what she proposes] will require considerable effort in the practical realm of collection development, financial planning, and institution building” as if she hadn’t considered the possibility. Others, like Laura Raicovich, he responds to more earnestly and even cites approvingly. It’s telling that Weiss counters one of her central arguments, that museums are not and cannot be politically neutral, by quoting Victoria and Albert Museum director Tristram Hunt: “Of course they are not pure, neutral, and wholly objective, yet museums embody a rigor, transparency, and curatorial knowledge base that can only help to foster an educated citizenry.” I longed for, and did not find, an acknowledgment that there are other valid and valuable forms of community knowledge that might “educate” the museum in turn.

I understand that someone leading an institution with an endowment of billions, around seven million annual visitors, and more than two thousand employees wouldn’t want to “move fast and break things.” But in my opinion, the conservatism inherent in the position makes Weiss misidentify the “greatest risk to the museum today.” He claims that it is the fact that the museum is a “visible, soft target—even if it is also a beloved one—for those seeking platforms for radical societal change.” A few pages earlier he had ratcheted up the stakes even higher: those people, like himself, “who would preserve a more limited role for the museum recognize the vulnerability of the institutions they have built and, more generally, the fragility of civilization itself.” It’s hard for me to accept political stance-taking on issues of culture as leading to the destruction of civilization.

One thing Weiss gets right, and expresses well, is something that would have been useful had it been a guide for the rest of these chapters on present-day cultural controversies. “What is most remarkable about this process [of people coming to know a museum as “theirs”] is how distinctive the museum becomes for each person—a bespoke version of the great institution reflecting specific tastes, rituals, and experiences. I know of no other kind of public space that can do this for people in quite the same way.” To me, this is both true and why the museum matters. And the gravest problem facing them is not that some protestors might unfurl a banner in the Great Hall or, though I might disagree with the tactic, splash some soup on a canvas protected by glass. It’s that the large art museum, as it’s currently constituted, does not allow enough people to find themselves—and feel themselves embraced in—its offerings to come to know a museum as theirs. Weiss suggests replacing the term “encyclopedic museum” with “universal museum.” But neither term acknowledges that a museum is made of and for individual people.

By coincidence, another new book, altogether different in its aims, makes a more convincing case for why a place like the Met matters. About fifteen years ago, Patrick Bringley, then working in the events department at the New Yorker, lost his twenty-six-year-old brother to cancer. As part of his grieving process, he applied for and was accepted as a security guard at the Met. He stayed for ten years, and his book All the Beauty in the World (Simon & Schuster; buy via Bookshop or Indigo) is a record of that decade, as he came to terms with his loss and started his own family. Transforming his pain, we see, requires him to slowly open himself up to companionship—with both artworks and colleagues.

Being a museum security guard is unusual in several ways. It’s a service role in which you are often invisible. It alters your relationship to time: “I can’t spend time. I can’t fill it, or kill it, or fritter it into smaller bits. What might be excruciating to bear if suffered for an hour or two is oddly easy to bear in large doses.” And it brings you into contact with all manner of people, not just the highly educated white-collar strivers he met while working at the magazine: “The glory of so-called unskilled jobs is that people with a fantastic range of skills and backgrounds work them. White-collar jobs cluster people of similar educations and interests so that most of your coworkers will have similar talents and minds.”

At the same time, regular and extended exposure to artworks changes your relationship to them, and to your understanding of yourself. “With experience,” Bringley writes, “I’m coming to know that some works of art reward long looking while others give back less, and you often can’t guess at the outset which will be which.” And at the same time: “I learn not only to choke back any snobbish impulses I might have, but to dismiss them as stupid and absurd. None of us knows much of anything about this subject—the world and all its beauty.”

The book is filled with not only a record of such personal evolution, but also the kinds of details that bring the institution to life. Guards get an allowance of eighty dollars a year to buy socks. There are signs in basement corridors insisting that people must “yield to art in transit.” Vendors on the plaza out front will sell a hot dog to guards for only a dollar. In a museum “the size of about three thousand average New York apartments,” these details ground his narrative in ways that I wished had peppered Weiss’s book.

Guards work in teams and, over the years, he becomes close with some of those he partners with on eight- or twelve-hour shifts. And in their conversations, both in the galleries and in nearby pubs, the disconnect between their experience of the Met and that of people like Weiss is made explicit. A long list of “supporting characters” near the outside of the book ends with “a lot of people one sees somewhat less, like curators, conservators, and executive types.” “Over our drinks, we talk about a slow creep of changes at the museum that feel corporate and impersonal to some of us, rolled out after long-time director Philippe de Montebello hung up his hat” in 2008.

What persists throughout these changes, of course, is the opportunity to commune with artworks. Bringley lovingly describes his encounters with a millennium-old Chinese hand scroll painting, a Persian miniature painting of a dervish, quilts made by Black women in Gee’s Bend, Alabama, and a painting of a crucifixion by Fra Angelico, among other artworks and objects. One of his pieces of advice is sound, and resonates with my own first encounters with these same treasures: “The first step in any encounter with art is to do nothing, to just watch, giving your eye a chance to absorb all that’s there.”

The Met, and other great museums like it, also has an absorptive power. It’s capacious, allowing students copying paintings, people avoiding afternoon thunderstorms, broken souls in search of healing, and millionaires visiting their donations to each find their place. And I don’t only mean that they all fit in its two million square feet, but that it also enables each of them to find what they need. Museums are imperfect. They’re made up of people—generations of people, each of whose personalities and proclivities leave an imprint on the institution, which should really be understood as anything but faceless.

One last story. In addition to my autodidactic streak, during Bringley’s tenure as a guard I also made a habit of visiting the Met on Friday nights with the woman I would one day marry. We’d walk in, have a quick kiss at the base of the grand staircase, and go our separate ways, each in search of some new treasure we’d never before studied. She often sketched. I’d write down some notes. After half an hour or so, we’d reconvene and show each other what we found, talk about what excited us. We often stayed until closing time; for all I know, Bringley could have shooed us out the door. Fulfilled by the experience and flush with the excitement of each other’s company, we’d go out together into the night.

Love all ways,

Brian

🔗 Good links

- 📚 Fourteen years ago (!), I wrote about another, far more gossipy history of the Met

- 🚵🏻 REI to eliminate “forever chemicals” by 2026

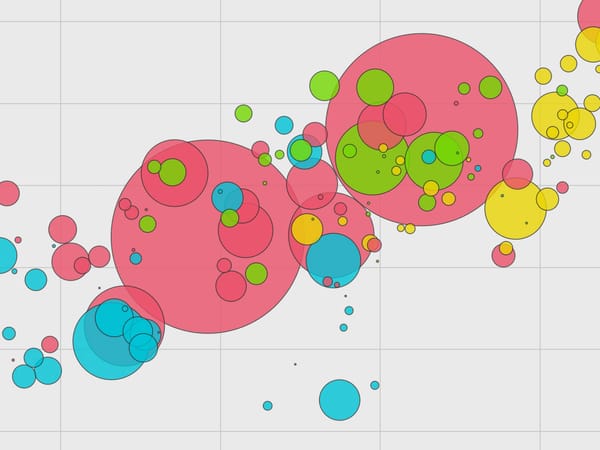

- 📊 Digital studio Upstatement on “using data visualization to drive change”

- New York architects recycle architectural mockup as a garden shed