Together Forever

Caroline A. Jones discusses “Symbionts,” biology, and mutual responsibility

Art historian Caroline A. Jones and curators Natalie Bell and Selby Nimrod have organized “Symbionts: Contemporary Artists and the Biosphere,” an exhibition on view at the MIT List Visual Arts Center through February 26, 2023. The fourteen included artists explore what it means to be interdependent or collaborative through their engagement with living entities such as fungi and bacteria. The exhibition grows out of research and conversations with a panoply of artists, scientists, and philosophers and is accompanied by an extensive catalog, published with MIT Press, that includes newly commissioned essays, reprints of important writing, and a roundtable discussion on symbiosis, reciprocity, and Indigenous epistemologies. –Brian Sholis

Frontier: The research you and your colleagues undertook for “Symbionts” straddles biology and philosophy. Notions of entanglement seem to have emerged in those fields, at first tentatively, in the 1960s. Can you talk about some of the theoretical underpinnings of the exhibition?

Caroline A. Jones: The piece of ’60s history that most engaged us emerged from an effort to build a new genealogy for so-called “bio art.” It’s a useful category, but one the artist Eduardo Kac has virtually trademarked through his advocacy. His definitions tie it to technologies through notions of “code.” Over the last decade I saw an increasing number of artists working with living or once-living materials who are not themselves interested in “the code” of those materials. They’re interested in what biologists would call epigenetics, the study of how your behaviors and environment can affect the way your genes work in the real world, outside a petri dish. In this project, we find another heritage in Systems Art, and we link these artists particularly to Hans Haacke and his work with biological systems like the 1967 sculpture Grass Grows. Haacke was himself influenced by writer-sculptor Jack Burnham, who was then writing about Systems aesthetics. Like those precursors, the artists in our exhibition recognize we are all part of systems and that what we do has consequences, debts, reciprocities, and responsibilities.

Frontier: Your catalog essay draws upon the ideas of evolutionary biologist Lynn Margulis. How did she reorient the field of biology and why has it taken decades for her ideas to begin proliferating across the field?

CAJ: A lot of the awareness of Margulis comes from the field of science studies, particularly my own MIT colleagues in the Science, Technology & Society (STS) program. These are scholars who study the tendency of science to separate, isolate, and sidetrack certain ideas. Margulis was a hero of the theorist and philosopher of science Donna Haraway—remember, Haraway got a PhD in biology. A lot of people, women especially, felt estranged from mainstream science and ended up in these critical positions. My colleague Evelyn Fox Keller is another: she came out of mathematical biology but felt she had to leave the field in order to comment on the dominant thinking within it. So these amazing feminist philosophers of life come out of biology and have been inspiring to me ever since I was a baby feminist. I’m following their lead in pointing to the importance of Margulis’s work.

Margulis stubbornly remains within science, despite not getting funding, and insists on becoming her own popularizer. She had to turn to and gain traction in the public theater of ideas for those in her own field to appreciate her notion of symbiosis. Will she win a posthumous Nobel? No. Biology is still driven by a petri-dish mentality; symbiosis requires observations in the field. Margulis’s work, and that of other scientists with a similar stance, is difficult, unrewarded, underfunded, and challenging.

By contrast, the work of culture is cheap and easy and fast. We’ve embraced that and made an exhibition that creatively points to these powerful ideas.

Everyone involved in this exhibition willingly collaborated with unknown entities. That requires a tremendous amount of care, of forethought.

Frontier: Language is an important aspect of ideas gaining widespread acceptance. In the catalog, you talk about how Anicka Yi, one of the most well-known artists in the show, is a prolific phrase-coiner, and about how many of the exhibition’s keywords—plants, culture—have multiple meanings.

CAJ: I’m in the neologism corner myself, though I recognize we should be sparing with coining new words. Anicka and I have productive arguments about this. Language is, above all, something that brings us together—and can bring us along together.

It’s fascinating—and sometimes distressing—to watch how words get pushed and pulled into new uses. For example, global companies still use vegetal words for purely industrial agriculture—hogs are “ripened” before being “harvested” and “processed.” We’ll need new words to help us understand how things are connected on a planetary scale. I think words associated with life should remain the purview of the living. Bios should be yoked to the biosphere.

Frontier: Staying at that larger scale, you’re clear that “Symbionts” is a social project, an attempt to change our minds in order to change our behaviors. Several authors in the catalog acknowledge this is a utopian endeavor. Can you talk about the value of attempting to create social change through the medium of artworks?

CAJ: Well, first, the utopian functions as a way to critique the present. I think of our project as a modest utopian proposal, something you could fold up and stick in your pocket. Maybe it’ll start composting, fermenting new ways of being. The only way people change is incrementally—then all at once. A little bit of change, a little bit of change, then suddenly we’re in a new world.

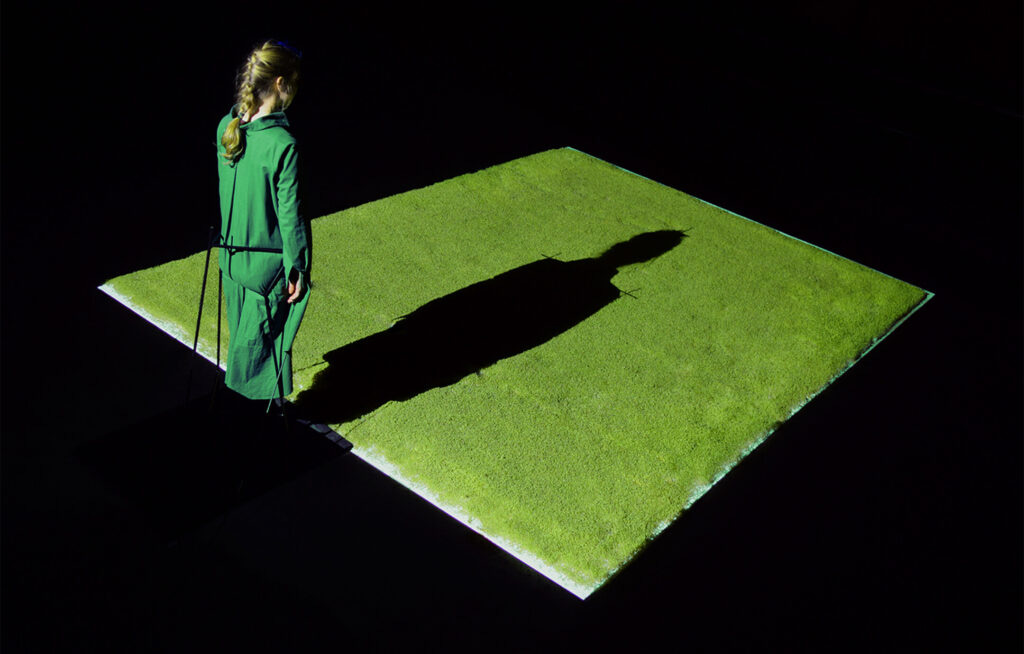

By emphasizing art, not utility, we think there is much more scope for the imaginary and the theoretical to inspire audiences and readers. At the level of homily, I’ll mention the artist Špela Petrič. Her Skotopoiesis project has taught me to be aware and to be grateful, to not take life for granted. It nudges me to figure out how to give back, to ask, “How can I be in a reciprocal relation with everything around me?” That thinking is also indebted to the Indigenous belief systems about reciprocity and relations with the more-than-human that also inform the exhibition.

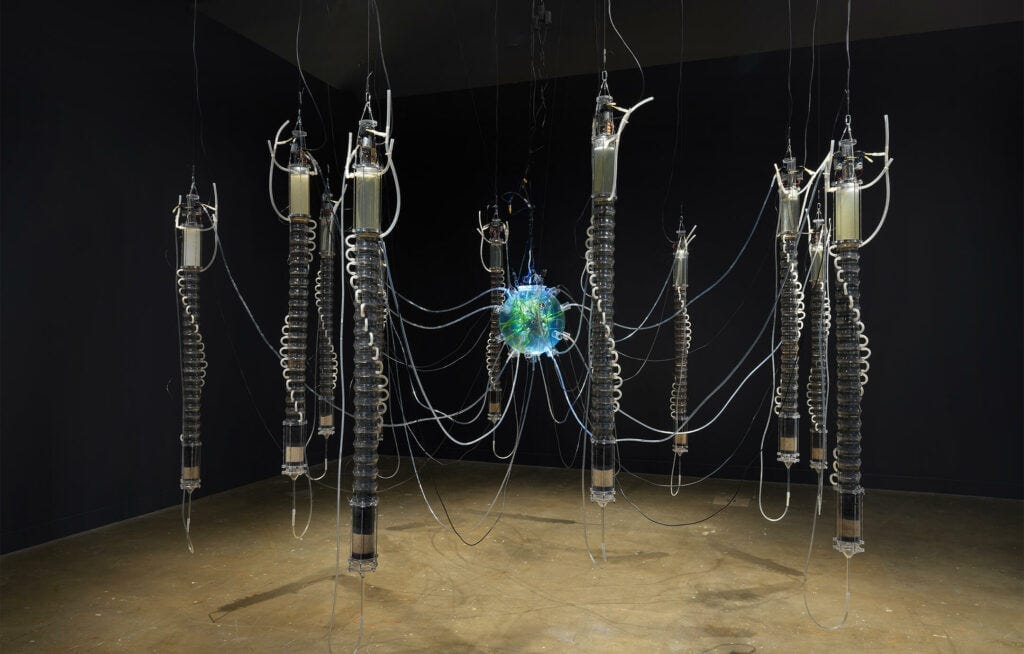

Frontier: The artworks in the show are presented individually, as per display convention. But because several are enacting biological processes during the show, is there a situation in which the artworks might commingle? Could that also be a metaphor for ideas and for creativity?

CAJ: That would be cool, though hard to track. Could a spore in one artwork “contaminate” another? If one of Kiyan Williams’s microbes starts growing on one of Nour Mobarak’s spheres, does she recognize it as being from Kiyan’s work?

I’ll say, one giant pressure when mounting this exhibition was the justifiable concern of MIT’s environmental-health-and-safety team. Anytime the word fungus is introduced, anxieties flare up—as was so beautifully expressed in Mary Douglas’s 1966 book Purity and Danger. There’s another reference to the ’60s.

What’s interesting here is that these artists are willingly collaborating with unknown entities. That requires a tremendous amount of care, of forethought. I’m grateful to the artists, their collaborators, and all the teams at MIT who helped make the show happen. Their efforts are in some sense an example of the openness and connectedness we hope the show models.

These artists demand that we unify ecology with economics. That’s the tremendous task we have ahead of us.

Frontier: I think of science journalist Ed Yong’s I Contain Multitudes (US, CAN) as a useful further introduction to this topic. Are there other texts you’d recommend to people interested in exploring these ideas further?

CAJ: I prefer Merlin Sheldrake’s Entangled Life (US, CAN) because he grounds his speculations about life in direct observation—he is himself a scientist. He also happens to be a fantastic writer and it’s a beautiful book about how fungi “throw our concepts of individuality and even intelligence into question.”

I’m also very interested in whatever Indigenous botanist Robin Wall Kimmerer writes next. And there is a growing body of multispecies ethnography emerging out of anthropology, of all places. And design is somewhere in the mix. I respect the creative practice of someone like David Benjamin of The Living or the London-based duo Cooking Sections. There is a deep effort among some of these practitioners to consider circular economies, which is inspiring.

When I stand with a group in the first gallery of “Symbionts,” I remind people that an artist like Claire Pentecost, whose work is in that room, is demanding that we unify ecology with economics. That’s the tremendous task we have ahead of us. This is just one tiny little utopian prompt to get us moving in that direction.