Workin’ on It

The labor movement comes to the arts, architecture, and the tech industry

Last week, I sent the first Good Links dispatch to paying subscribers. Our promise is no paywall, so that post is now free for everyone. Click through for more stories related to recent issues and lots of links to read, listen to, or watch. If you enjoy it and have the means to support our work, please consider becoming a paying subscriber.

Hi everyone,

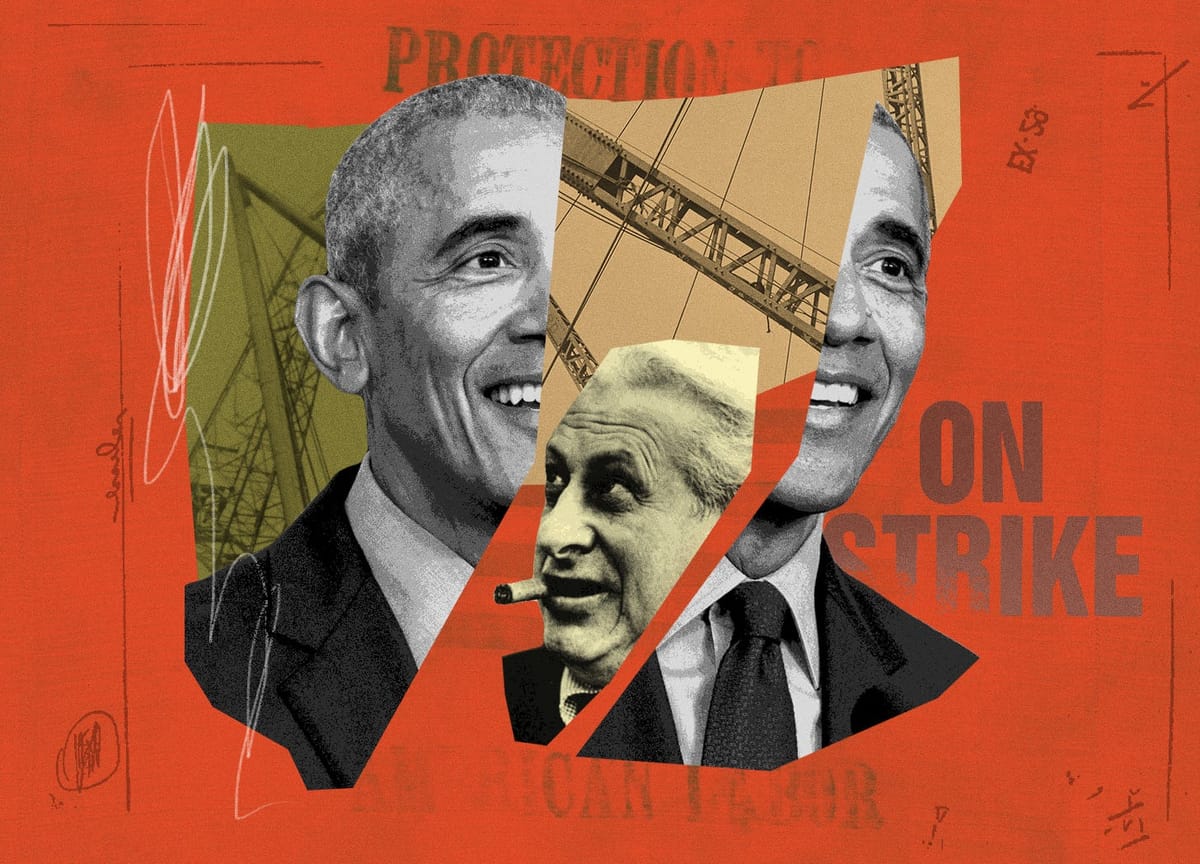

I don’t have much in common with former US president Barack Obama, but we do share deep ties to Chicago, a love for reading history, and an admiration for the late writer and broadcaster Studs Terkel. Those overlaps mean Obama’s latest venture, the Netflix series Working: What We Do All Day, vaulted to the top of my streaming queue.

Half a century ago, Terkel published his own book titled Working, drawing together oral histories with more than one hundred Americans into nine thematic stories. An immediate bestseller, the book attempted to show how people found not just a living but also meaning in their work. In retrospect, there was irony in publishing such a book in 1974, just as the post-WWII “consensus” between management and labor was breaking down. In that decade, the number of new unions, which had helped workers bargain with employers since the the mid-’30s, plummeted starkly. The marketing of Obama’s new series explores how, in the ensuing decades, “Americans have faced explosive changes in the way they work, all in the face of increasing inequality.”

It’s an opportune moment to revisit the subject because workers in many industries have recently made vocal and increasingly successful pushes to form unions. This includes those those in the arts, the built environment, and technology, the sectors I focus on here and where unions have historically been uncommon.

In the last few years, alongside calls to decolonize art museums and increase pay equity, employees have formed unions at two dozen institutions, including the Guggenheim, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the Musem of Contemporary Art Los Angeles. New to this movement is the participation of “white-collar” workers in curatorial, administrative, or educational roles.

A parallel push has emerged in architectural offices, with the staff at Bernheimer Architects recently becoming the first private-sector architecture union in the US. In December 2021, a big New York Times story focused on a union drive by the architects at SHoP, the prominent New York firm. But a sign of how difficult the road can be came barely three months later, when that campaign was called off. Speaking of the challenges, Andrew Daly, a union organizer formerly on the staff at SHoP, said, “We are groomed to devalue our time and labor from day one of architecture school studio.”

And while media attention has rightly focused on Amazon logistics workers’ unionization efforts, advocacy and organizing has also taken place among software engineers, product managers, and others in tech giants’ perk-filled offices. Attention-grabbing walkouts have spurred interest in collective action that has so far yielded thirty-seven publicly documented tech unions.

Unions figure into only one part of Obama’s Netflix series. And there is abundant criticism that he has promoted the project while the people who write Netflix’s scripted productions are on strike. The most direct condemnation I read is from writer Hamilton Nolan, who diverted his initial frustration into a more hopeful note: “The silver lining of Obama disregarding a strike in order to promote a show allegedly in homage to Studs Terkel is that it really drives home the fact that the labor movement today has a power that Obama-era Democrats can’t even understand.” The confidence of that statement may be a little ahead of the facts in the arts, architecture, and technology. But there is definitely a groundswell of activity worth paying to.

In the meantime, two more recommendations. The first is WFMT’s Studs Terkel Radio Archive, which contains more than two thousand of his programs. The collection spans four decades and includes conversations with many figures who are likely of interest to readers of this newsletter: R. Buckminster Fuller, for example, or John Cage and Merce Cunningham, or Marshall McLuhan.

Another is writer Craig Taylor, who produced two of my favorite oral histories in recent years. The first, Londoners: The Days and Nights of London Now (buy via Bookshop, Indigo), introduced me to a city I know only glancingly. The second, New Yorkers: A City and Its People In Our Time (buy via Bookshop, Indigo), refreshed my understanding of a city I thought I knew intimately.

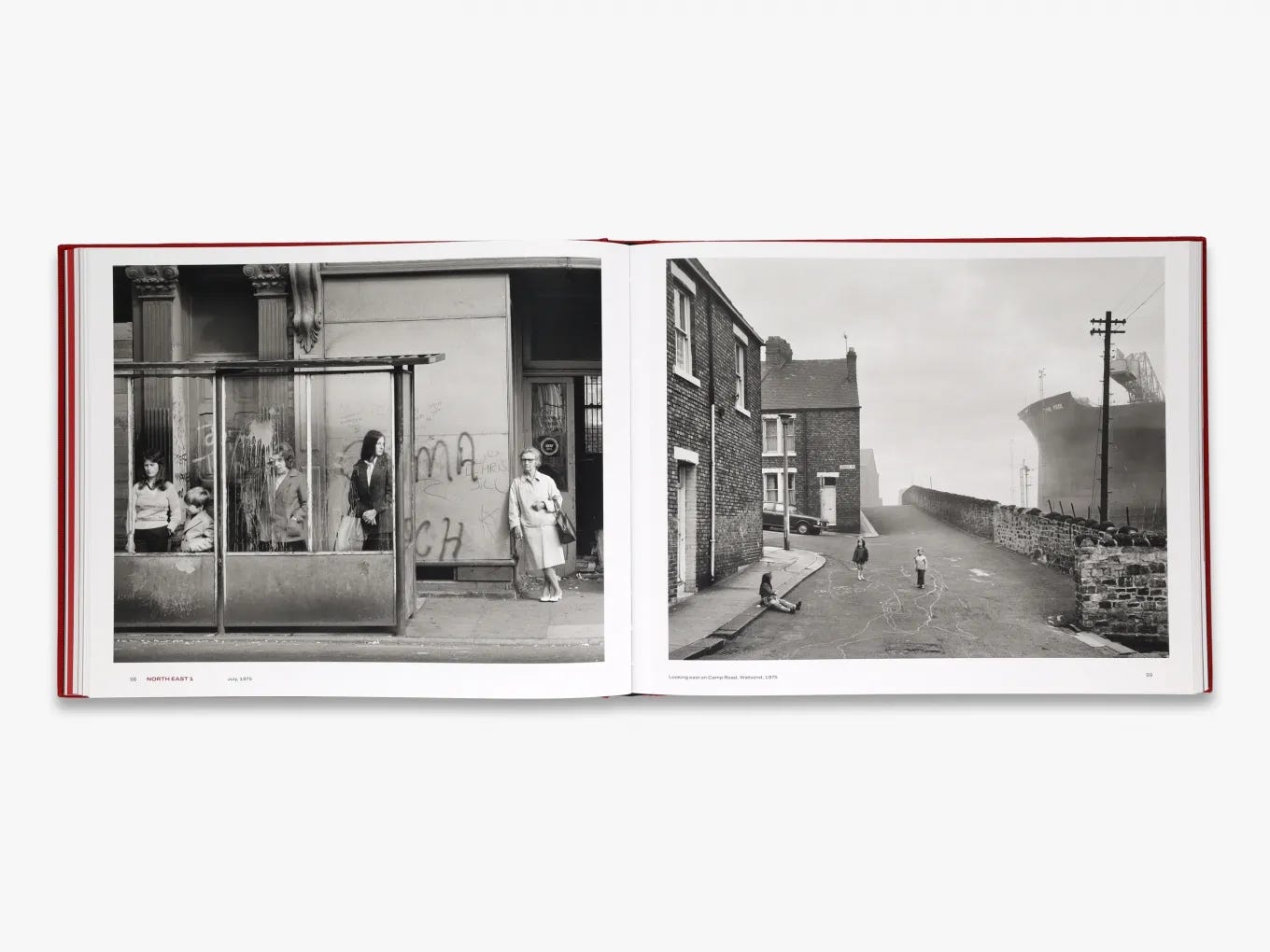

By coincidence, I recently got my hands on a copy of Chris Killip (buy via Bookshop, Indigo), a new book surveying the late British photographer’s astonishing documentary work. From early pictures taken on the Isle of Man, where Killip grew up, to celebrated series revealing how British life and labor changed in the 1970s and ’80s, Killip captured both people and places with an unsparing eye. But he also immersed himself in the communities he photographed, and one can sense his warmth and affection through the coarse textures and grime. As he said, “I’m not an historian and these people will never appear in history books, because ordinary people don’t.” Gregory Halpern, himself a wonderful photographer whom I’ve written about elsewhere, writes, “[Chris] spent a lifetime photographing in places where he had built relationships, where there was trust and respect. That dynamic is the first thing I see when I look at Chris’s pictures.”

In his lifetime, Killip’s art was widely respected, distributed by Magnum Photos and taken up by serious but not flashy institutions. Later in his life he revisited some of his series with the celebrated photobook publisher Steidl. This volume accompanies a major survey at the Photographers’ Gallery in London, whose director, Brett Rogers, notes, “through the medium of photography Killip lifted the veil on an unequal and troubled country—without melodrama, but with clear-sighted tenderness and unwavering resolution.” I hope the exhibition and book introduce a new generation to Killip’s humane art. But if you can’t access either, I still recommend spending time with his pictures on the robust Chris Killip Photography Trust website.

Love all ways,

Brian

🔗 Good links

- 🎯 Because [Chicago architecture critic Blair] Kamin writes as a booster for the city […] his work doesn’t take account of the complicated ways in which architecture is necessarily sutured to the ebbs and flows of global capital.”

- 🎞️ Happy for the Toronto-based artist Lotus Laurie Kang, whose work is now on view at the MCA Chicago and soon to open at Chisenhale Gallery in London

- 💪🏻 “You must fight for what you believe to be right while never losing your sense of humor or your sense of proportion.” Neil Gaiman’s three-minute address to graduates of embattled New College in Florida.

- ⛰️ “I was struck by the strange power music can have. Here was an event so small and ephemeral—there were no more than 80 people in the chapel—it was almost as if it did not exist at all.”