Renovation Project

Owen Hatherley celebrates the urban residential complexes denigrated in North America as “the projects”

Hi everyone,

For nearly two decades I’ve enjoyed reading the architecture critic Owen Hatherley, first on his blogs and later in many other outlets, from the LRB and The Guardian to Jacobin and the New Left Review’s Sidecar. Most of that commentary focuses on his native Britain and the built legacy of communism across Europe. So I was eager to read Walking the Streets, Walking the Projects (buy in the US or Canada), his new book on New York City and Washington, DC. Its focus on large-scale “projects” offers a useful counterpoint to the book Emergent Toyko, which I wrote about a month ago. My thoughts on it are below an Olympics follow-up and our weekly links.

I checked online, and a monthly subscription to Frontier Magazine is cheaper than a four-ounce container of Perfect Pinch Salad Supreme Seasoning. If you enjoy receiving these missives, why not spice up your life—and the lives of all the free subscribers—by supporting us? Click “view this post online” then one of the subscribe buttons.

Until next week,

Brian

🏋🏻♀️ A follow-up

Two weeks ago, I asked: “Will the Olympics die out before host cities learn how to harness them for good?” With the Games starting yesterday, lots of publications are now weighing in. Michael Kimmelman, writing in the New York Times Magazine, answers, “The question is no longer whether the Olympics benefit cities—history tells us they’re mostly good for the wealthy, if anyone—but what success might look like.” By the end of the piece, he remains ambivalent, with no clear definition of success in sight. In The Dial, a new-ish and wonderful independent magazine of international literature and reporting, Phineas Rueckert writes about “how the Olympics exacerbated the housing crisis in Paris.” These are weighty and important topics, ones that will continue being discussed now that France and Salt Lake City have been announced as hosts of the next two Winter Games. But of course you’ll also want to look at pictures of buildings, so here’s Dezeen’s guide to the architecture of the Paris 2024 Olympics.

🔗️ Good links

- 🏢👀 Buildings that caught my eye: a low-slung market in Khorfakkan, UAE, that runs next to a highway in the Hajjar Mountains and is built from stones excavated for a nearby tunnel; a brooding row of terrace houses in suburban Stockholm; landscape architect Teresa Moller’s house on Chile’s coast

- 🇱🇧🗺️ The Living Heritage Atlas | Beirut documents and visualizes the city’s craftspeople and catalogs its crafts through an open-source database; see also this interview with its lead researcher

- 🔎🅿️ The Google Visitor Experience team’s story about a new on-campus parking garage “purposely designed to not be a parking garage someday” (h/t Sentiers)

- 🚇🚌 “New UK study finds that older people are significantly less likely to die (of all causes) if they ride transit.” (h/t David Zipper)

- 📚📝 Places Journal’s Summer 2024 bookshelf: mini reviews of ten recent books on architecture, landscape, and cities, including several I considered writing about here

Renovation Project

Owen Hatherley opens his new book, based on two brief visits to the US in the past decade, by outlining what he calls the New York Ideology. This “exciting way of reading and understanding the city … privileges, and politicizes, direct observation.” Descending from Jane Jacobs, patron saint of the “sidewalk ballet” in dense, walkable neighborhoods, this ideology has grown to encompass writers on both sides of the political spectrum, ranging “from the black queer science fiction writer Samuel R. Delany on its far-left, to James Howard Kunstler, the grumpily conservative theorist of a small-town New Urbanism, on its far-right.”

But, Hatherley argues, the elevation of her most famous book into a kind of scripture overlooks a key flaw in her thinking: her denigration of large-scale “projects”—housing, mass-transit, and other efforts that remake large parcels of the urban landscape. As she put it in the late 1950s: “the underlying intricacy, and life that makes downtown worth fixing at all, can never be fostered synthetically. […] You’ve got to get out and walk. Walk, and you will see that many of the assumptions on which the projects depend are visibly wrong.” In seven “walks” through New York City and Washington, DC, Hatherley wants to use her preferred technique—roaming about on foot, then writing plainly and sharply about what you see—to help us revalue the urban places so despised from the 1970s onward that many were demolished.

This effort doesn’t begin in earnest until the third chapter, after he’s spent seventy-odd pages giving an acidic and sometimes quite funny tour of contemporary Manhattan. Based on a brief visit in 2014, Hatherley writes approvingly of Rockefeller Center and the High Line, and dyspeptically about many other places, like the “overbearing digital trash” of Morphosis’s recent academic building for Cooper Union. He’s particularly good at noting how European influences shaped the island’s earliest tall buildings, which “makes Manhattan a fascinating, compelling place to walk, because hardly anywhere has ever combined being quite so backwards with being quite so futuristic.”

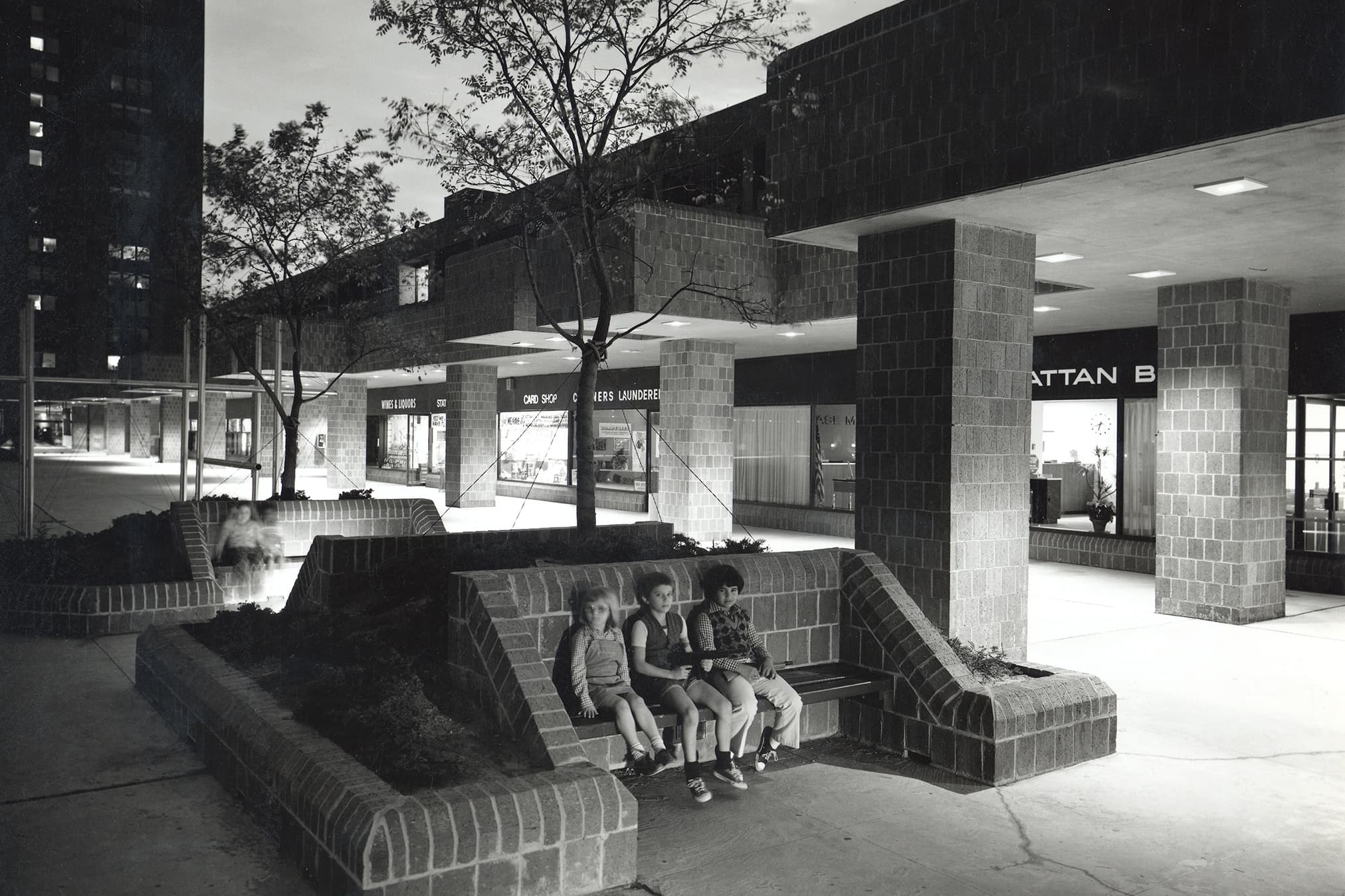

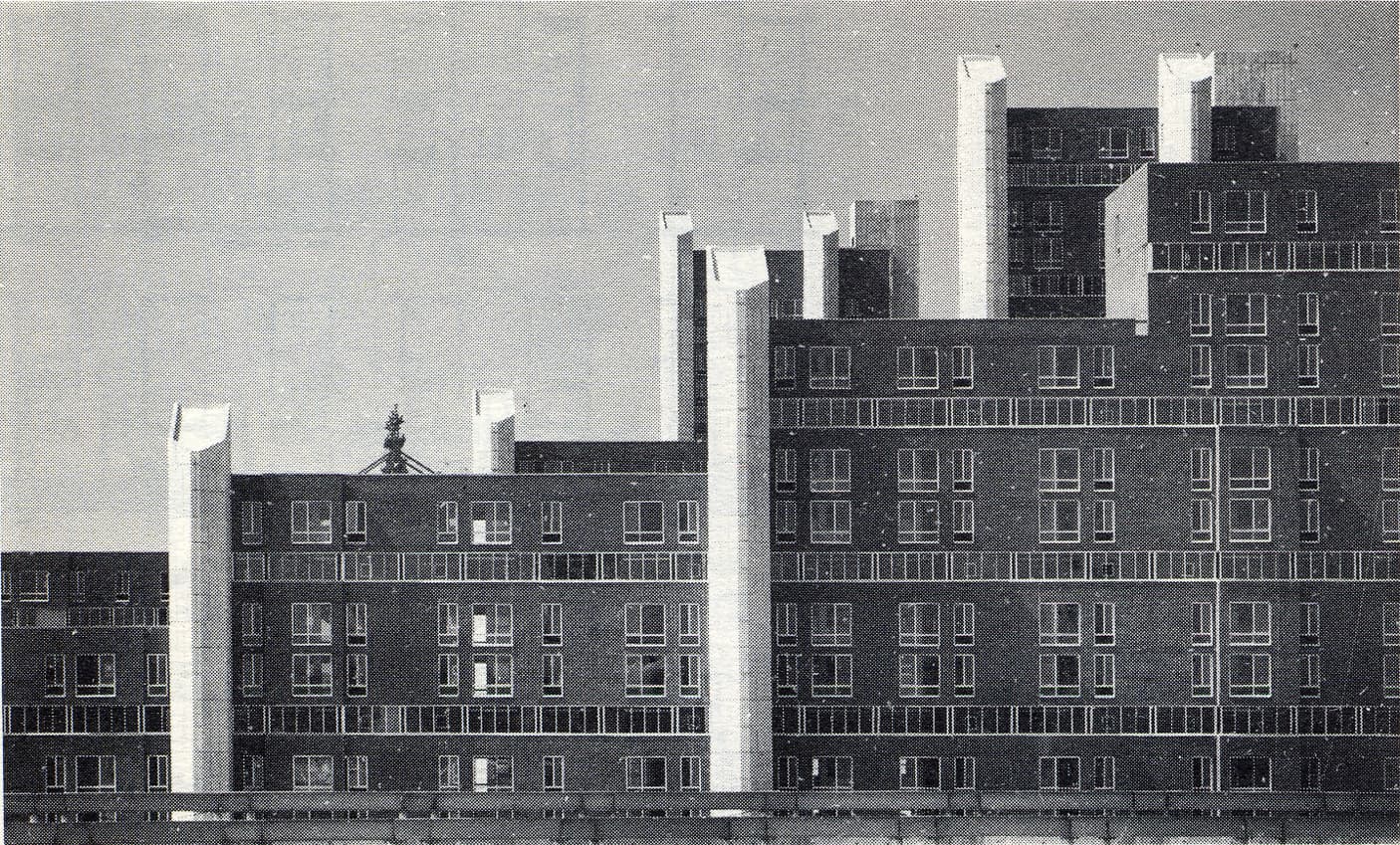

But neither the Woolworth Building, completed in 1913, nor the new World Trade Center towers completed a century later offer the “adventures in social democracy” promised by his subtitle. That begins, instead, with a rousing celebration of Josep Lluís Sert’s apartment buildings on Roosevelt Island, completed in the early 1970s: “Tall, articulated, chunky brick and concrete blocks, with strongly expressed, heraldic concrete service towers and balconies … run alongside a pedestrian-only promenade.”

Hatherley’s deep experience with Soviet, post-Soviet, Brutalist, and other mid-twentieth-century architecture enables him to see details that other eyes might gloss over. Indeed, it’s the details that can make or break a project. Waterside Plaza, a four-tower project on the East River designed by Davis, Brody & Associates, “looks robust, well-made, and the sense of space and vastness created by the river has a real sublimity to it.” Williamsburg Houses, a mid-1930s low-rise Brooklyn complex designed by Richmond Shreve, William Lescaze, and other architects, with its blue tiles at building entrances and windows set into corners, “is as good mass housing as you would get anywhere in the world, at the time or since.” These contrast with the “monolithic, institutional” look of other sites he visits, like Queensbridge Houses and Stuyvesant Town. Yet even these have redeeming value, in the mature trees and green spaces that occupy most of the land without removing residents from the bustle of nearby main streets.

Hatherley grounds his observations in the details of funding and politics that led to, and structured the evolution of, these projects. Some were built by labor unions, others by government entities, still others in public-private partnerships. He’s good on the United Housing Foundation, which built multiple cooperative complexes with generous interior specifications, and on the flaw in the Mitchell-Lama Housing Program that allows developers to privatize the buildings, usually after twenty years.

“Mitchell-Lama is gone as anything more than a legacy, but the idea that public-private partnerships are the way to solve the failures of the free market in housing endures here.” That’s what leads to neighborhoods like Long Island City, just across a busy boulevard from the Queensbridge Houses. Over the past two decades, developers have constructed a forest of glassy condo towers featuring more than thirteen thousand units. Despite generous subsidies, only five percent of those units have been set aside for lower-income residents.

The privatization of so much subsidized housing demonstrates that securing a large pool of enjoyable working- and lower-middle-class urban housing requires not eyes on the street, but eyes on the term sheet. The market won’t provide it. Aggressively cost-cutting public projects, as seen in places like Chicago, is a recipe for eventual demolition. The value of Hatherley’s book resides in how he criticizes attention to these extremes, then points to successful projects that show “how it is wholly possible to build a project on a human scale, to break up the grid without being monolithic, to make something that feels public and communal without feeling regimented and institutionalized.” I know the value of these projects, having lived in one early in the last decade, and like Hatherley remain cautiously optimistic that in North America we can build them again.