Sari Azout

On thinking with the door open and building knowledge together

Episode Transcript

Introduction

Sari Azout: I come back to this question of feelings, right? At the end of the day, I want my internet and my life to be full of joy, connection, wisdom, intellectual curiosity. I want to feel creative.

Brian Sholis: I’m Brian Sholis, and this is the Frontier Magazine podcast. In today’s episode I speak with Sari Azout, who builds digital products and advises and invests in startups. In 2012, not long out of university, she co-founded Bib + Tuck, an online marketplace for buying and selling clothes. After selling that company in 2015, she joined Rokk3r Labs and Level Ventures, where she has spent nearly a decade providing founders with seed-stage funding and advice on marketing, operations, and strategy.

In the past few years, I’ve appreciated Sari’s repeated calls for more humane digital platforms and tools and enjoyed participating in the community she fostered through a product called Startupy. She joined me from her home in Miami to discuss the ideas and ideals underpinning her career choices, the promises of networked knowledge-sharing, and how that product, Startupy, has morphed into a new company and tool, called Sublime. Thanks for listening. Here’s our conversation …

Conversation

Brian Sholis: Your career, in the broadest terms, has been a progression from investing analyst to startup founder to VC investor to startup founder. And I wonder if you can just talk about that back and forth, and how you apply the lessons that you’ve learned as you move from one track to the other.

Sari Azout: I think that the throughput throughout my career, regardless of what side of the table I’ve been on, is this idea of collecting and connecting the dots. As a venture investor, your job is to connect ideas across disciplines, see the patterns. To understand how one thing you’re seeing in one place can apply to another. You’re doing that a little bit more abstractly because ultimately, as an investor, you’re judged by your ability to select great companies. But I think my interest in the field really came from that ability to connect ideas across disciplines.

I’m a builder by nature. I like to imagine and build things. In some ways, part of what I’m doing with Sublime is sort of like productizing this sort of feeling of collecting and connecting the dots, which has been just such a big part of my life.

I grew up in Colombia, in South America, and I remember as a little girl, I would just love watching TED Talks, and it’s very sort of cerebral. Little me would probably not be too surprised to know this is what I’ve ended up doing and building.

The test of a piece of software or a machine is the satisfaction it gives you. There is no other test. Technology is meant to serve humans and not the other way around.

BS: I think connecting the dots is probably something that’s become increasingly important to knowledge work more broadly, not just investing or working in technology. And I think that maintaining access to high-quality information and being able to discern signal from noise are increasingly important skills. I guess I want to ask about what may be a point of frustration. Can you recall one of the first times that you felt overwhelmed by the knowledge available about a subject, or when you felt like a Google search let you down while you were hunting for a piece of information?

AZ: All the time. We are living in the golden age of human knowledge, but it hasn’t triggered a golden age for human flourishing. And I think that, you know, I’m not an economist, but I actually think that a lot of these numbers are backed up by statistics around productivity. You would imagine that having all of this time and knowledge and information would do something for us. But ultimately, I think that as a society, the most obvious and relatable consequence is that we’re just distracted all the time.

And I think that once you have all this information, what’s missing is depth of understanding. Because the answer is usually not more information. It’s how do we actually deepen our attention? How do we deepen how we engage with that information? And I guess I’m in the Marshall McLuhan school of thought where, you know, we shape our tools and then they shape us. In many ways, I believe that we’ve designed our information-consumption environments in such a way that we’re essentially consuming ten-second, bite-size micro-installments of dopamine. And that’s just not conducive to deep thought. And so I think it’s no surprise that so many of us feel like we have so much information, but that’s not making us wiser, more knowledgeable, or increasing our ability to make sense or make meaning.

BS: I first encountered you espousing these ideas in about 2019 or 2020 through your newsletter, Check Your Pulse. And I think you described that newsletter as about tech and startups, but designed to make you feel human. As an investor, you were always seeking meaningful differentiation in the companies that you were considering. What about designing something so that it makes you feel human felt like meaningful differentiation at that time? What in technology and the newsletter landscape was missing and why did you want to emphasize the human element?

AZ: With the newsletter, I just started writing and I had no idea what it was about. And then at some point I was like, all right, I need to describe this newsletter. And it dawned on me, from looking at the archives, that the thing that I was most interested in is this idea of just bringing more humanity, creativity, and delight to business and technology. You know, in some sense, the things that make us feel great, that make us feel alive, that bring us joy are not the most quantifiable. Designing for delight: like how do you measure that? How do you compensate someone for that? But they are the things that give our lives meaning.

I was very interested in, you know, how do you design for emotions and how do we bring that mindset to the tools we build? Because the test of a piece of software or a machine is the satisfaction it gives you. There is no other test. If the machine makes you feel calm, then it’s great. If the machine makes you feel anxious, then it’s not great. Technology is meant to serve humans and not the other way around. Serving humans means we’re just feeling better about ourselves. We’re happier. We’re more joyful. We’re more connected.

When I think about Sublime and what we’re trying to build, I always think of a filter or a litmus test for anything new that we build: does it make people feel more intellectually nourished? Will it make people feel more creatively charged?

BS: Yeah, maybe we can talk a little bit about the progression to Sublime. Because I think while you were writing that newsletter, you were also investing and also collecting information and the names of companies and people who are dedicated to the same ideas. Maybe you could just talk a little bit about the database that you built for yourself that led, you know, years later now to a tool that you’re sharing with other people.

AZ: Yeah, let me walk listeners through that journey. So I never expected that a database that I started to build when I was sitting in an office, running a venture fund and then running strategy for a startup studio, would later become what it is, which is, I think, a true testament of how ideas take time to slowly marinate and develop and and grow and have a life of their own. I mentioned that my job essentially was to hang out at the edges of the internet, find interesting content, collect and connect the dots, synthesize them into something new.

And whether I was investing in companies or creating some sort of strategic presentation for a client, that was the work that I was doing. And I think that more than the outcome, the raw ingredients of that outcome was just a good information diet. I guess at some point I realized my memory fails me and it doesn’t make sense for me to, you know, every time I’m talking to a client that has a marketplace, for me to have to resurface this thing again. And so, anyway, for my own personal utility, I started cultivating this database.

Initially, it was super simple. Every time I’d see an article, I would just clip it. I would tag it with relevant topics or concepts. I would add some highlights to them. And then, there were other areas of my life where I was needing to organize information. So one was interesting companies that I was seeing and the other was interesting people, agencies. And I had these three separate databases. And then one day I said, let’s combine them.

I took advantage of the newsletter as a sandlot to experiment with some of these ideas. I initially sold access to this database, and I think it was about four hundred people that paid for it. So it was instant evidence that human curation is valuable.

And that sort of led me down the path of, okay, so I’ve got this database here that I’m nurturing for myself. It’s proving to be very useful in my work, but why am I doing this alone? Why aren’t other people building on this? Why aren’t we doing this together? For lack of a better term, I decided to call this database Startupy, put it in some janky interface, and invited other people to contribute.

When I put this product out there and this community started building around it, what I realized is that what was exciting, I think, for people is this idea of having a more communal way to build your intellectual resonance library, your second brain, your personal knowledge library. I think we live in a world where there’s so much information and we need little gardens to make sense of them. We need places to store and sense-make. And ultimately, everything new is a combination of older things we’ve seen. And so we need to be able to curate and recombine these things. But so many of the tools that allow us to do that are single-player.

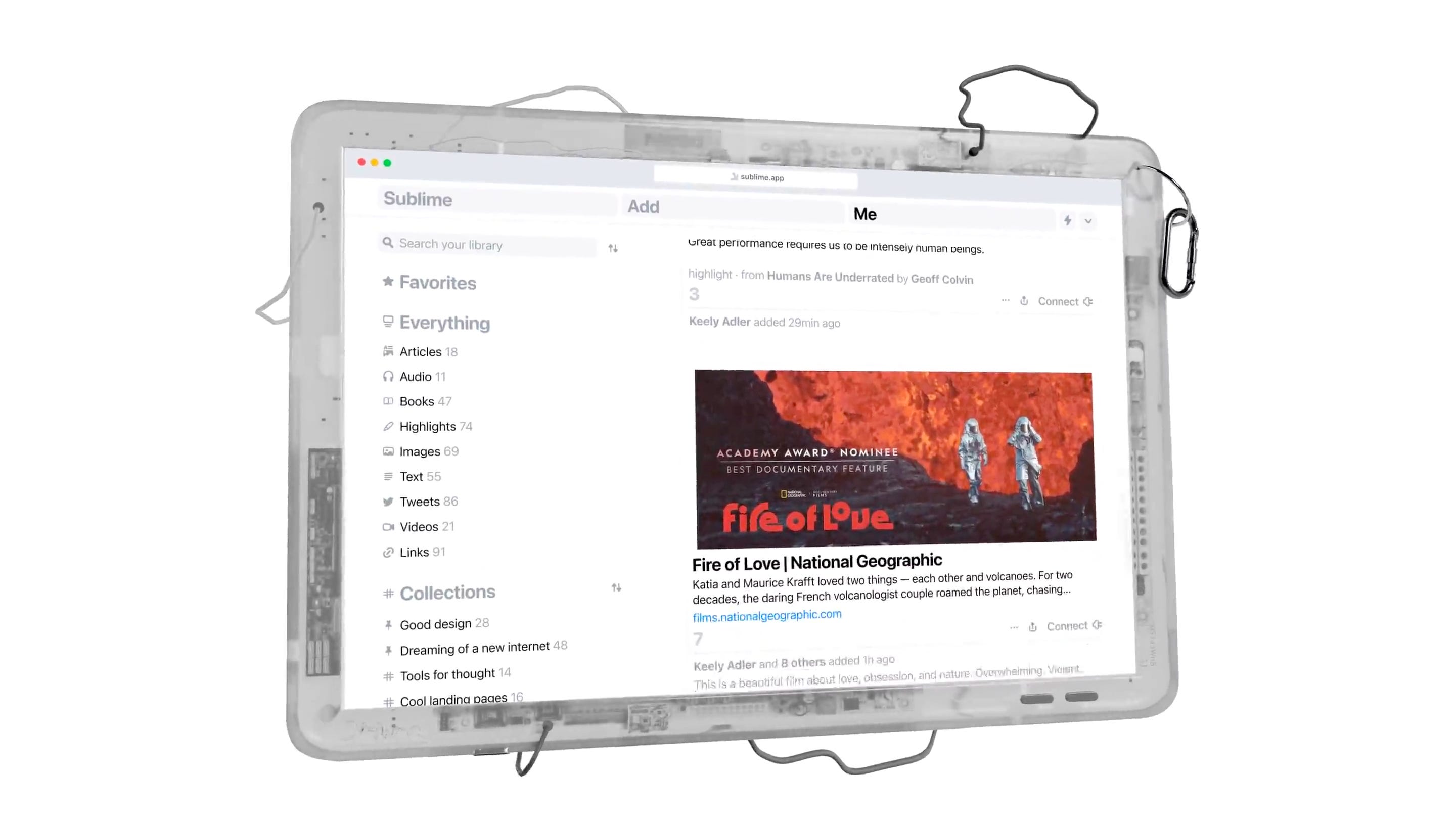

The design challenge that I’ve embarked on over the past year is, how do we build the simplest interface to help people collect and connect the dots in a more communal environment? We’re combining the focus and utility of a tool for thought, a productivity tool, a note-taking tool, a bookmarking tool—whatever you call it—with the sense of aliveness of a network. And to do that effectively, you really have to understand how networks work, why certain networks drive us to behave in certain ways, and then how the note-taking productivity tools work. It’s been an interesting challenge to marry those things and arrive at a foundation that we can build upon.

BS: Can you talk about how trust plays into that, both in terms of trusting the information that you’re getting access to through a communal or multiplayer tool, but also in terms of human flourishing, in terms of community formation, in terms of finding other allies in a landscape that’s populated with tons of people who all have their own agendas?

AZ: Trust is so important. I always say that information can move at the speed of light, but trust can only move as fast as the rate at which humans can form deep bonds and connections. And I don’t think that technology meaningfully changes that. When you ask about trust, a couple of things come to mind.

You can ask a chatbot a question and the chatbot will respond and you will have no idea what sources, what—you know, it’s an entire black box of how that information was summoned. And people use ChatGPT every day and similar tools, and there’s no stopping that. And that’s gonna continue to happen. But I think the opposite of that is also going to happen, which is that, at the end of the day, people trust people. And on Sublime, there’s always a human—you understand how something got to where it is. With all of the SEO-optimized, like, dehumanizing web, where so much of it is optimized for convenience but you really don’t understand the incentives. Everything else is a black box. Putting humans at the center sort of changes the trust mechanics.

So if I need to know the menu for a restaurant, then I’m gonna go to Google for that. But if I want insights on how to build a strong brand, I don’t want to Google, “How to build a strong brand,” I want to see what Brian is reading about branding. In a world that is changing so fast, it’s also important to ask, what is not going to change? And I think that me trusting you, because we have a relationship, knowing that you understand the world of branding and then trusting and being curious about what you’re reading, that’s just a universal feeling that I don’t think will go away.

BS: Yeah, finding a signal in the noise is labor. And why not distribute that labor among as many people as possible, so that we don’t all have to slog and that we can all benefit from each other’s work.

AZ: I think so many of us are already doing that work, but in private, fragmented corners of the web, you know, whether we’re highlighting something on a Kindle or, you know, in our own Apple Notes or whatever systems we use. I think that most people would be comfortable exposing parts of that archive, at least. And it’s so interesting for other people to be able to peek into someone’s mind in a way that’s not performative, that it’s still a utility, it’s still useful for you, but there’s some serendipity that comes from leaving the door open.

BS: One of the things I haven’t heard you speak about much is the … we’ll call them playful experiments that you ran during the time that you were writing Check Your Pulse and then also when you were running Startupy. One that stuck out in my mind is called Ghost Knowledge. It was trying to elicit knowledge that existed but maybe wasn’t shared. I wonder if you can just talk about that little experiment and whether or not things like that taught you anything that you’ve brought forward into the work you’re doing now.

AZ: I guess the first thing is that I love the idea of having a drop model to explore different ideas. So I think we’ll continue to create things. I really want to create an infinite game. The goal is to just run interesting experiments, connect interesting people, [and] build delightful, amazing products. Ghost Knowledge specifically, the thesis was that, yes, there’s a lot of information, but there’s also a lot of a specific type of information. Because if you think about who is incentivized to produce information, it’s journalists, it’s content creators. And so there’s a lot of perspectives in the world that are missing [in our information diets], right? And I call that ghost knowledge.

The spirit of that project was: what if we could invert the model and have you say, “Oh, I would like this person to write about this [subject] and I will pledge for that.” It was a success in the sense that it generated about 10 essays, canonical pieces of writing on the internet today.

The amount of money [involved] was not huge. Eugene Wei, for example, wrote something as a result of Ghost Knowledge. And I think that overall, not more than $700 was pledged. He was still excited because the idea of people pledging beforehand and saying, “Hey, I want you to bring this to the world.” It’s less about the money at that point.

BS: Sublime, as we speak, is still in a private beta. And so the broader audience does not yet have access to it. But I wonder if you can just talk a little bit more about some of the reasons that you chose to morph the product from Startupy, which had a specific name and a specific valence, to one called Sublime.

One thesis of Frontier, the company that I work for, is that design accelerates positive change. It’s no longer sufficient that something be good for people or for the planet. It has to offer a great experience. And one of the things that you’ve spoken about is the importance of design in that transition from Startupy to Sublime. And I wonder if you could just tell me more about that and more also about why Startupy, the name, was a skin that you felt you had to shed.

AZ: Yes, yes, so many interesting questions and strands here. Startupy initially was positioned as this community-powered database of startup knowledge. The vision, I would say, was always bigger than that. People are curating their own little knowledge bases in private corners of the web. I wanted to stitch together these graphs. I wanted a simpler, more communal way to build a second brain. And I wanted the outcome of that to be a human-curated graph of the best ideas on the internet.

So a lot of these ideas were there from the very beginning. I think that Startupy was missing a strong notion of product design, taste, usability, and individual utility. What I mean by that is people were very drawn to the mission because the mission was exciting, but there wasn’t a clear, like, “What does this product do for me right now that I’m gonna make it a part of my life?” from the perspective of a curator.

The first thing we had to shed is, Startupy was like, it was never about startups. We actually got a ton of questions from people saying, like, “Oh, I’d love to, you know, add like a ton of resources on consciousness. Can I do that here?” And that’s when we realized the name is going to forever hold us back. A name has the power to shape a product and how it’s used, to evoke a certain set of feelings. So in the back of my mind, I always wanted a new name.

And it wasn’t until Sublime came to us that it felt like this is actually perfectly capturing the feeling that we want to evoke. Because the Sublime, the quality of things that have aesthetic, intellectual, moral greatness, is exactly what we want this platform to be. What philosophers call the sublime is this paradoxical feeling of both being extremely overwhelmed by the vastness of nature, but also feeling at one with it. Yes, it’s very overwhelming to be in this world. There’s a lot of information, but we could also be a powerful center of knowledge and wisdom in our own little gardens and tending and nurturing our own little spaces. The moment that we stumbled upon Sublime, it felt very clarifying.

BS: My background is in art and the one painting in your art history class that is most closely associated with the sublime is Casper David Friedrich’s Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog. And that idea, that phrase, a wanderer above the sea of fog, maybe is a useful analogy for the kind of person who’s attracted to and might be using Sublime as a service.

AZ: Love it.

BS: You know, I went back to the first issue of Check Your Pulse just to see what was in it and to understand what carries through to this day. And there’s a surprisingly strong connection there. I mean, you said that you would never send people anything that you haven’t read yourself. You wouldn’t fill people’s inboxes for the sake of filling their inboxes. You were not only going to focus on the new. It sounds to me like those principles have really carried through.

I think one of the ones that most appeals to me also is to not only focus on the new. Because so many things on the internet today are geared to continually serve up the new. And even if you have an algorithmic timeline that does not serve you the newest, very newest thing, it’s still only serving up what’s recent. I wonder if you can just talk a little bit about the value of older knowledge, the value of remaining in touch with ideas that have persisted.

AZ: I think about this a lot. It’s very shocking that we’re just a click away from the greatest authors of all time. And yet we are spending hours and hours and years of our life just scrolling feeds sorted by recency. In some sense, you have to sort of interrogate, like, why is that? There’s some sort of path dependence on the internet. You could also talk ad-based business models. They have to keep us coming back for more and hijack our attention. So there’s all of that.

I often tell people that I’ve like, for the most part, with very few exceptions, stopped reading the news. I only consume things that I believe I will want to read again or come back to a year later. And if you have that filter for how you consume, then it weeds out most of what’s out there. It felt like the right and obvious choice for me, but I still get looks and stares when I tell people I don’t read the news. Oh, you’re not keeping up with the politics and the facts of the day.

And I actually believe that one of the biggest problems with our current media environment is that we are constantly context-shifting. So we see one tweet about this and another about this and another about this, and we can’t go deep in any one area. If you are spending your life and your days consuming the news, then chances are you can actually do nothing meaningful with it—because there’s always more. Whereas if you can tend to your own little garden and choose a few things that you want to really go deep on, become really good at, there’s just so much more power waiting for people in the depth of things than there is in the shallows.

I’m very interested in slow media, thoughtful media, depth. I think that we have the power to change that by building a new set of tools that is optimizing for more than just the novel and the ephemeral.

Our goal is resonance, not scale. The town square, that metaphor on the internet, has been built. We’re not trying to replace that.

BS: If that last question was about longevity in one direction, things carrying forward from the past, maybe I can ask you a little bit about how you’ve set up the business of Sublime for longevity moving forward. I’ll testify to the fact that I prefer to use software that’s entirely bootstrapped, that there’s a business model where people are making the money that they use to run their tool from the people who use it. From what I understand, in Sublime, you’ve raised a small funding round and are using that to kind of get the product up and running and to start refining it. But I wonder if you can talk a little bit about that decision to do that, but then also how that sets you up for and what your longer-term plans are for Sublime.

AZ: I love this question. I’m thinking about it all the time. So, yes. So to concretely answer that, our intention is to build Sublime to be a sustainable company that is paid for by its users. Because when you’re building a product that people will pay for, then that’s a forcing function to make it useful for people instead of to serve … a different set of constituents.

Because we’re in a private beta, we haven’t fully baked in payments, the payments flow, but we do have a believer tier. And I’m just astounded and I giggle every time I open my email and see that people are buying a lifetime tier just as a testament that what we’re building resonates.

A few other important points to make here. I think that our goal is resonance, not scale. And what I mean by that is I believe that the town square, that sort of metaphor on the internet, has been built. That’s Twitter and Instagram and YouTube. They’re like places that are ad-mediated, designed to have a billion people on there. And, you know, regardless of whether you like them or not, that already exists. We’re not trying to replace that.

When I think of Sublime, I think of a neighborhood cafe where everyone’s invited, anyone can go, but it self-selects for a certain type of person. Not everyone’s going to go to the specific neighborhood cafe that plays the jazz music that you like and has a certain type of vibe. So it’s not designed for everyone, but it is open to everyone in a way that, say, the private party or the private Slack group or the private Discord is not.

Why can’t we build Sublime to be incredibly meaningful for a smaller subset of people? And me and my mighty team of three people just work our butts off every day to make it amazing and better. I’m just very excited by that set of incentives.

There’s a lot of promise, I think, and experimentation to be done around building products that are laser-focused on serving the people that use them but also making sure that they’re not exclusive.

BS: I ask that question both in terms of curiosity about the business side of things, but also because you have written elsewhere that the future of search is boutique, that Google is not going to—that anything that’s geared to indexing all the world’s information is not going to be useful really for almost anyone who’s trying to find certain kinds of context-dependent knowledge.

And that idea of something being smaller runs up against a utility question whereby if not enough people are using Sublime, then perhaps the sense of magic that you’re hoping for from the multiplayer mode, of discovering things that other people have added to the database, may not work as well. That you may run up against the boundaries of the knowledge that’s contained within the platform. So I wonder if you have a sense of—it’s not necessarily a number, but what are the metrics or what are the ways in which you think you’ll recognize when you’ve reached a sufficient amount of both people who are using the tool and then also kind of the amount of knowledge and types of knowledge that are indexed using it.

AZ: I think we don’t have all the answers. We have a lot to learn. But first, it has to be useful without the network. I do think the network is what will make it magical over time. But when you look at single-player alone, when I look at the personal knowledge management space, I think that these tools are falling short for a subset of people, me included. A lot of these tools—I’m thinking of sort of something like Notion, Roam, Tana—they have excessive customization and a very steep learning curve. Many people don’t want to build the tool. They just want something that has the right defaults and has somebody that’s thought through, what is the right way to build my knowledge library without having to think about how to structure it and all of those details. So that’s the first piece.

The second piece is that these are typically low-ROI products. And what I mean by that is they’re information-storage tools. They’re not knowledge-generation systems. Most people [using them] just collect a bunch of stuff. They don’t surface it again. They don’t create new forms of knowledge. And when I think about Sublime, our job—and what we’re most excited about now that we’ve put out this foundation—is how do we actually transform this tool from just an information-storage product to something that can help you generate insights.

And we think that those things, if we can get them right, they’re useful without the network. We’ve got this magical, amazing, small community that’s formed around Sublime. We’ve got about 30,000 people on a waiting list right now and only have let in a small subset of them. But what we expect is to make the product so magical in single-player mode that it can have utility without the network.

BS: And maybe as a final question, let’s assume that the principles behind Sublime take root with a large community and then filter out into the broader internet. What do you want your internet to look like in 2030?

AZ: I come back to this question of feelings, right? At the end of the day, I want my internet and my life to be full of joy, connection, wisdom, intellectual curiosity. I want to feel creative. All of these words that I don’t feel accurately describe most people’s experience on the web today. We need more people that actually are taking shots of building this and manifesting these ideas into pixels. I certainly don’t have all the answers, but certainly have a lot of clarity on what that should look and feel like.

Thanks for listening to this episode of the Frontier Magazine podcast. It’s the audio component of our weekly publication, which features appreciations from the forefronts of architecture, technology, culture, and education. Each issue shares new ideas about how design and creativity accelerate positive change. Everything we publish is available for free; browse the archive and sign up for new issues at magazine.frontier.is. If you liked this episode, please share it with people you know and rate us to help others discover what we’re doing.

The magazine and podcast are products of Frontier, a design office in Toronto. Here’s studio founder Paddy Harrington:

Frontier is a design office. We believe in the expansive potential of storytelling to help people navigate the unknown to get somewhere new. We’re coming up on a decade of designing big stories in the form of strategies, brand identities, editorial products, and digital and real-world experiences that help organizations, brands, and individuals stand out and discover new creative territory. Learn more at frontier.is.

Thanks again. I hope you’ll join us for the next episode.

This episode was produced by Heather Ngo. It features edited versions of “Thwarted Motion” by Ejeebeats, “4th Dimension” and “Sisvuit Cincvuit” by Joel Loopez, “Horizons” by Treiamusic, and “Lonely Ambient Texture” by Memomusic.