Second Life

Two very different projects that repurpose our waste

Hi everyone,

Though I’ve now lived in Canada for seven years, I remain more aware of and connected to American than Canadian Thanksgiving. This week I’m reflecting on the year to date, and one of the things I’m most grateful for is the opportunity to write every week—and to know that writing is being read. Thank you for joining us on this venture. I hope that, if you’re among the one-third of our readers likely celebrating, you’re doing so in the company of loved ones.

This week’s stories discuss projects that make creative use of our waste. One is a product recommendation, the first in a series that will draw from the ongoing conversations we have at Frontier about the design and production of physical products. (For context, see this story on the tuque we made a few years ago).

Love all ways,

Brian

Second Life

When I moved to New York in August 2001, the city announced a shortlist of landscape architecture firms that would propose redesigns of Fresh Kills Landfill, the largest repository of garbage in the world. After decades of citizen protests, this 2,200-acre site on the western edge of Staten Island had finally closed earlier that year. It was understood, even then, as a major development—not only a significant commission for the shortlisted firms, but also a step forward in municipal thinking and environmental planning. James Corner Field Operations eventually won the commission in 2003.

Fast forward twenty years: North Park, with walking and biking paths, an overlook deck, a bird-viewing tower, and a composting restroom, opened last month. Though less than 1% of the overall site, it’s a milestone in that this is the first new portion of the project opened to the public. As Corner said during the ribbon-cutting ceremony, “Once people get into the heart of the site, they will be astounded by the extraordinary scale and character of the larger park, with its palpable sense of nature, extensive vistas, and opportunities to explore.”

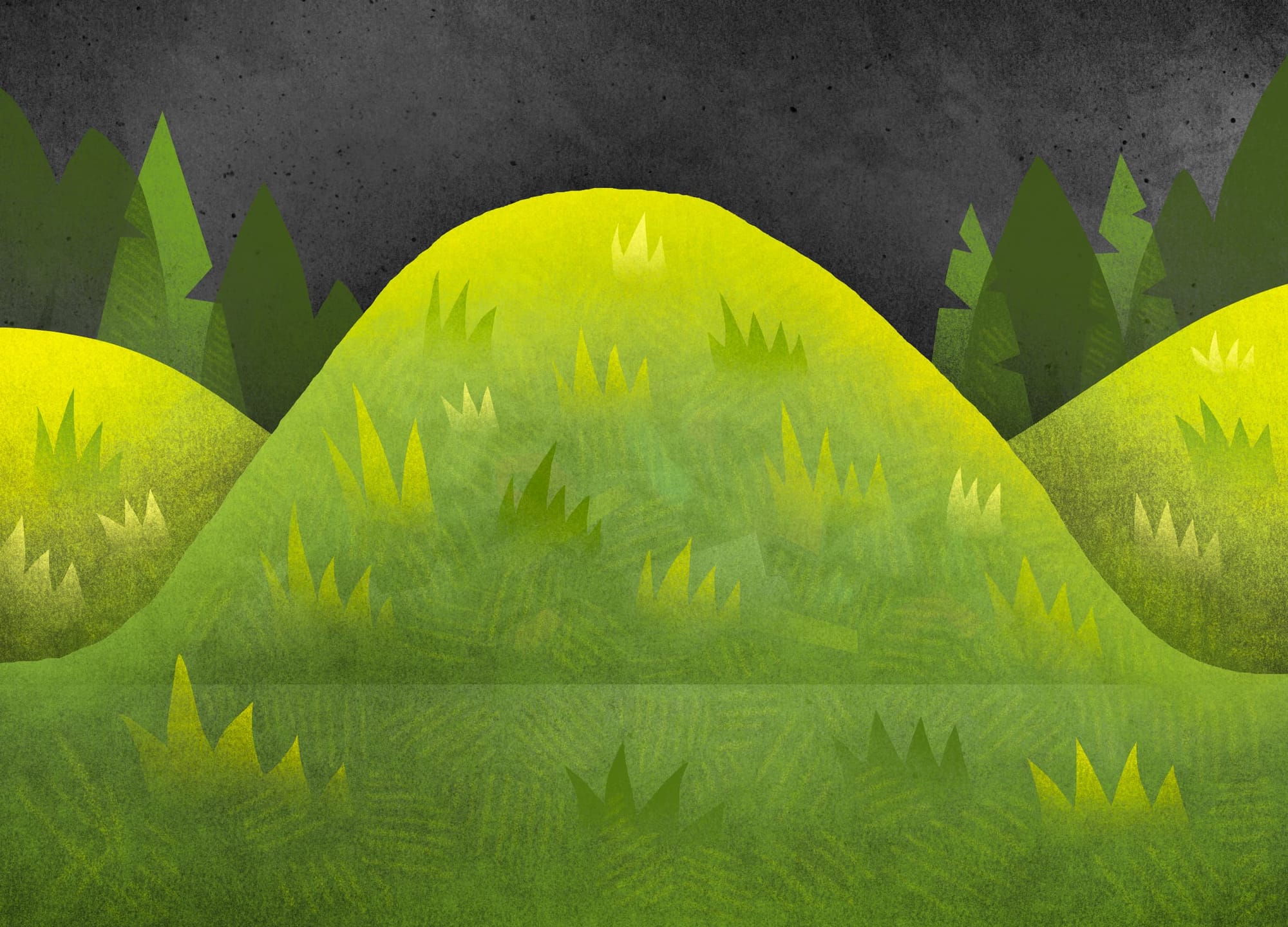

That nature is largely engineered: after all, the garbage piles had at one point been twenty stories tall. As Robert Sullivan noted in a 2020 story, “The four garbage mountains would be transformed into four soft green hills straddling the convergence of creeks. Tree planting … would occur in coordination with the careful engineering of what you might call the dump’s natural excretions, the methane and the leachate. In this way, over the course of 20 years, the parks and sanitation departments worked together with Field Operations to restore or encourage tidal wetlands, to generate forests, scrublands, and the wide-open fields of grasses.”

Mierle Laderman Ukeles, an artist who has worked with the NYC Department of Sanitation for over four decades, calls those hills “social sculptures”: “The former landfill one can stand on today was the product of these two engines: consumerism and fossil fuels. Using, living in, and passing through New York has produced the social sculpture of these mounds. I don’t want to forget that.”

For all the talk of transformation that rightly accompanies the new park, for all the new species alighting on these grasslands for the first time, I share Ukeles’s sentiment. New York is still sending its garbage to landfills, just ones located farther away. When I visit the park someday in the future, I’ll not only enjoy the trails and the views, but also try to hold in mind the site’s complicated past, with human influence that stretches well beyond the colonial era. It took decades to close the landfill; it is taking decades to rehabilitate its Staten Island site; and it’ll take yet more decades of awareness-raising and activism to reduce our great tides of refuse to a trickle. I’m hoping that in literally covering over mounds of garbage we don’t lose sight of that bigger picture.

☆ A little more: Jade Doskow is the Freshkills Park photographer-in-residence. A selection of her pictures illustrates Sullivan’s story; more can be found here.

Frontier Products: Vollebak Garbage Fleece

Frontier Products highlights well-designed, durable, people- and/or Earth-friendly items that demonstrate how to marry purpose and performance.

Vollebak, founded in London in 2015 by brothers Steve and Nick Tidball, designs performance clothing for an Earth shaped by climate change, pandemics, and instability—as well as the other worlds we may one day inhabit. Onetime ad men, the Tidballs know how to market their ranges, too: “Our apocalypse gear is built to see you through the collapse of civilization.” “Our 100-year range is designed to outlive you.” The company recently made headlines for Vollebak Island, an off-grid, carbon-neutral compound designed with architect Bjarke Ingels.

But the Vollebak product that caught our attention is less of a spectacle: the Garbage Fleece, launched last year. As the company notes, “Every second, a garbage truck’s worth of clothing is dumped into a landfill somewhere on Earth.” So this is Vollebak’s first attempt to repurpose materials—wool sweaters, plastic bottles, plant waste—headed to the landfill.

Learn more here. Read more about the company in this Outside magazine profile by Tom Vanderbilt.

🔗 Good links

- 📡 Apropos this week’s OpenAI drama, it’s instructive to read this recent story about Signal’s nonprofit structure and its running costs.

- 👩👦 “A toddler has a life, and learns language to describe it. An LLM learns language but has no life of its own to describe.”

- 📚 “We tried to design a book that would feel like it was a future that didn’t arrive, yet also wasn’t retro or nostalgic.”

- 🏗️ To Be Build, a Tumblr posting photos of in-progress architecture

- 🍫 From MoMA, a video about the science, skill, and patience that goes into papering a gallery with chocolate sheets.