Serve Yourself

Admitting we’re one with our tech—and doing something about it

Hi everyone,

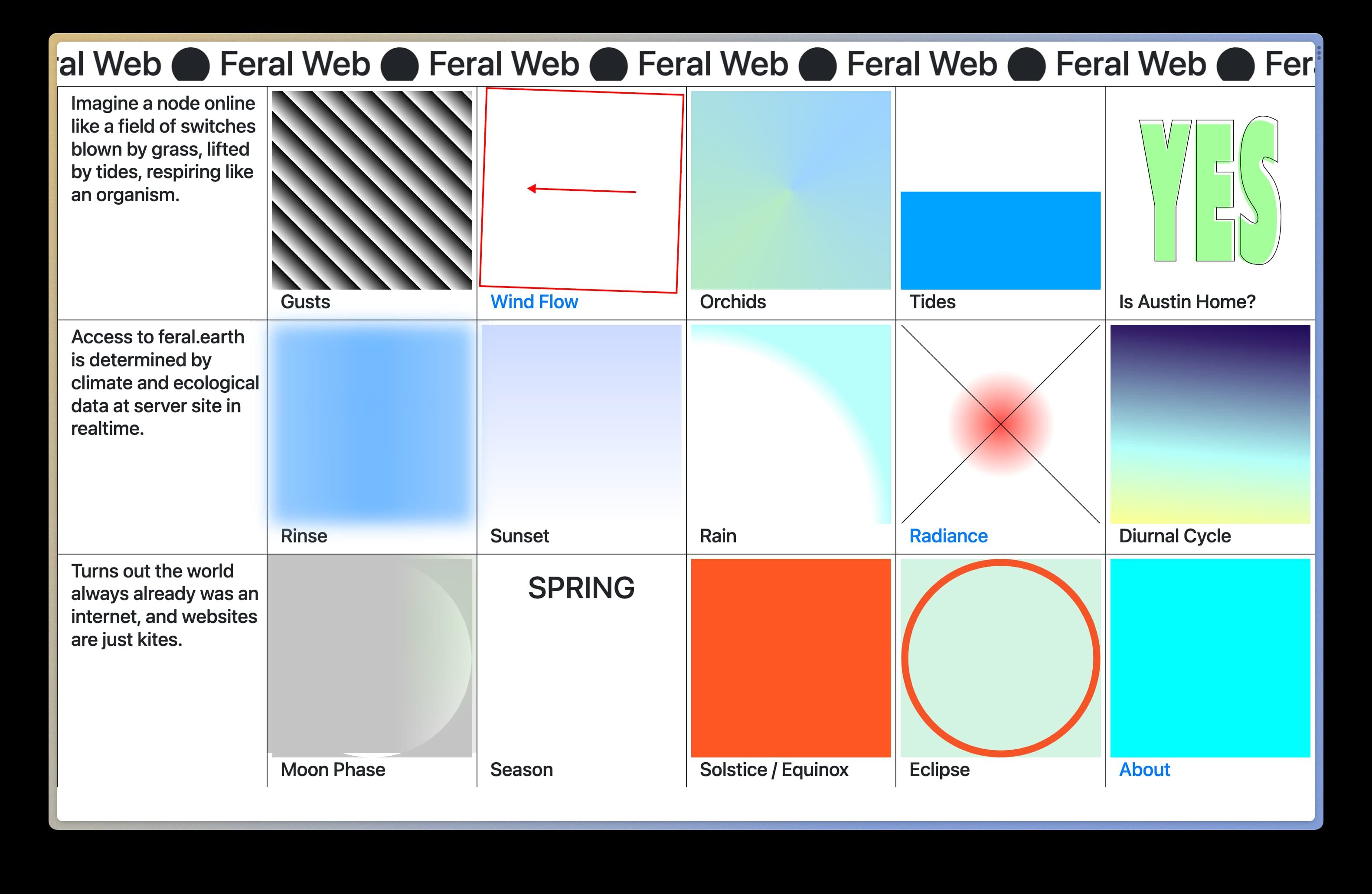

Last month, I was incredibly inspired by a new website. As best as I can tell, it contains precisely fifteen links. Despite visiting often in the past few weeks, I don’t think I’ve been able to click on more than half of them. That’s by design: access to the website, feral.earth, “is determined by climate and ecological data at [the] server site in real time.”

Feral Earth is a project by artist and technologist Austin Wade Smith. AWS, to use the name they often use for themselves, has powered a Raspberry Pi via solar panel; hooked the machine up to an Ambient Weather Station; and written scripts to change the site’s code based upon conditions like the direction of the wind, the tide, when the sun shines directly on its solar panel, and the current moon phase. They estimate that exploring the entire site will take approximately four months.

This kind of conditional access extends a lineage that AWS acknowledges, like Low Tech Magazine, and brings to mind other new projects, like artist Rick Silva’s commission for the Whitney Museum’s Sunrise/Sunset exhibition. It’s more distantly related to something you may be familiar with: the toggling of dark and light mode on your computer. But what makes Feral Earth particularly appealing to me is the essay AWS published alongside the site’s launch.

Titled “Queer Servers and Feral Webs,” it lays out a pragmatic but invigorating vision of entanglement with networked technologies. We are increasingly aware that, as science journalist Ed Yong outlined in his 2018 book I Contain Multitudes, humans need and thrive on partnerships with microbes, bacteria, and other animal species. AWS transposes this to our technological milieu: “I’m curious where I am supposed to end and the technology I ‘use’ begins. It isn’t a matter of extension, because that presupposes there is a discrete, essential version of myself which moves outwards into the world. We’ve always been environments.”

It’s a radical vision of personhood and identity that proactively acknowledges and reflects upon a reality many of us passively accept (or do not even recognize). And it elegantly sidesteps the kinds of crazed, VC-funded enthusiasm that leads to tech bros signing up for early access to brain-engineering projects like NeuraLink.

AWS links this thinking elegantly to their own non-binary identity and their preferred use of plural pronouns. It’s an identity I do not share, but the way they extrapolate from it to understand their relationships is deeply stirring to me. “As a practice of queering, I’m curious how my laptop, my websites, my servers are a part of me, and I like to play with the ways they render me to other people on the internet. The infrastructure which serves me to the world should be an active participant in my multitude.”

I don’t have the technical skills AWS has; it would take me years to learn how to create something like Feral Earth. But one direction in which I can take this inspiration is personalization, in understanding the tools I use as part of an ecosystem where we commingle, where we bend toward each other.

I spend nearly all of my work time sitting in front of a screen. And while I use the ergonomic levers to adjust my office chair for comfort, for a long time I didn’t think to do the same thing with my computer. PC, of course, stands for personal computer. But as desktops, and later laptops and smartphones, became more ubiquitous, they also became less personal—more like what AWS is arguing against in both word and deed. By “less personal,” I mean they were designed (with increasing success) to satisfy most people most of the time. The trade-offs inherent in that choice mean that, as web programmer Jack Wellborn recently noted, useful options and features are now often hidden. The defaults are good enough that many of us don’t think to improve them for our needs.

So I’ve been personalizing my computer. I followed Manu Moreale’s guide to minimizing the visual clutter in Apple Mail (though I haven’t gone quite as far as he has). I came across Nate Kadlec’s guides to making Google Docs and Google Sheets more friendly and created new design defaults that I find more pleasing. I found and installed some “boosts” for Arc, the web browser I use, that make the websites I visit often a little more accommodating. I installed Raycast, gave it a prominent keyboard shortcut, and created some snippets so I never again have to type my full address or email address—and never have to go hunting for that pesky × when writing about artwork dimensions or scheduling meetings).

Though some of these changes save me time, they aren’t about productivity. Instead, this process has been about making my laptop a better, more ergonomic tool for me, a comfortable and comforting environment in which to pass these many hours. It’s lightly turning something designed by teams working for companies in California into something designed by me for my own use. It’s the first step in a process that, when followed through assiduously, leads to end-user programming of the kind advocated by, among others, Geoffrey Litt. And eventually to projects like Feral Earth.

I’m grateful to AWS for writing an essay that has expanded how I see my relationship to the technology I depend on daily. If biodiversity is key to an ecosystem’s health, shouldn’t we encourage the radical customization and specificity (and eccentricity!) that leads to a similar diversity in our technology ecosystem? And, in doing so, how does that help us safely reveal more of ourselves to each other, to foster better relations?

So, I want to ask: what have you done to make your technological world better serve you? And how else can we narrate the fact that we inhabit our technologies the way we inhabit physical places? Reply to this message or use the comments below, and let’s start a conversation.

Love all ways,

Brian

🔗 Good links

- 👨🏻💻 Adam Wiggins’s 2020 series of short essays on “making computers better.”

- 🚉 Thomas de Monchaux argues for saving New York’s 1960s-era Penn Station complex: “Dear city, dear careless and avaricious city, for once get something right: just keep it and make it into a homeplace.”

- 📚 Via Shannon Mattern, “Rule No. 5,” an interactive exhibition about libraries: “It examines practices and objects that shape how we can search, who we will find, and what we remember.”

- 🌾 “What if the austerity is how we live now—and the abundance could be what is to come?” Rebecca Solnit on “what has been missing when we talk about the climate crisis.”

- 💡 The light grid defined 1980s futurism (via Craig Saila).