Shelter in Place

A new book offers ideas for how we can survive the “long emergency”

Hi everyone,

In this week’s New Yorker, the humor writer Patricia Marx notes, “Billionaires have recently been spending millions building themselves customized bunkers, in the hope that they can ride out the apocalypse in splendor.” She travels America, wondering, “But what about me—and, if I’m being generous, you. Are there affordable underground shelters available for us to hole up in?”

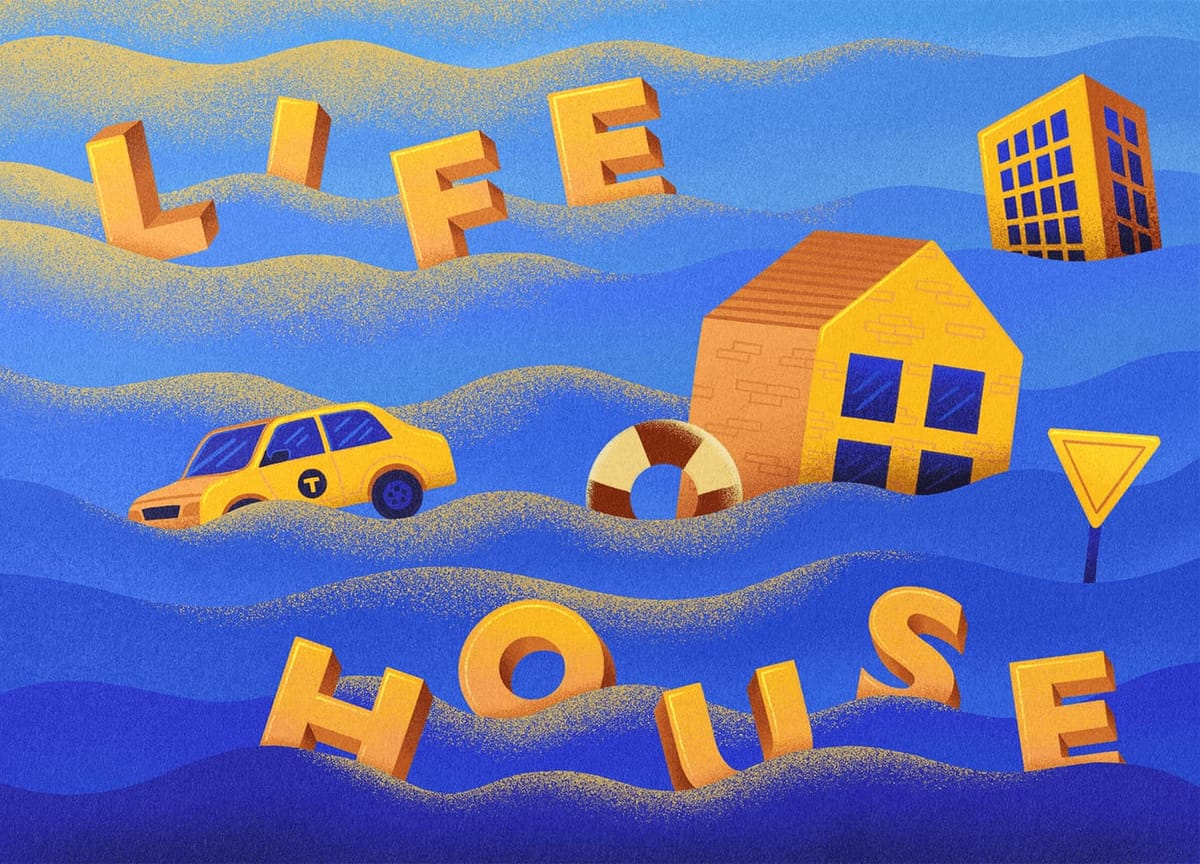

Unfortunately, I’m unable to buy one of the million-dollar bunkers she visits. By coincidence, this week’s newsletter is about what the rest of the rest of us have access to: each other. Below you’ll find notes on Adam Greenfield’s new book Lifehouse. In it, anarchy is not something “loosed upon” a community, to protect oneself against, but simply one way of describing the networks of solidarity and mutual care increasingly necessary “in a world on fire.”

With the future ahead of us,

Brian

🔗 Good links

- ⛱️🌞 “In the Eastern Coachella Valley, where shade is a luxury, the nonprofit Kounkuey Design Initiative focuses on empowering residents through design”

- 🥵🗺️ “Using Toronto as a case study, the maps below show how heat vulnerability can be quantified and how it varies across the city.”

- 🌧️🌿 “Inspired by the Netherlands, Montreal is adopting water squares to mitigate urban flooding.”

- 🗣️🫧 In architecture, “the thoughtful interpretation of projects has, by and large, been replaced by inhouse-produced press releases”

- 🏢♻️ Apropos the link above: in spring 2023, I wrote in passing about a building renovation in Brussels. The Architect’s Newspaper has just published a fascinating, and critical, followup.

Shelter in Place

In late 2012, I was scheduled to move into a new apartment, the first I’d ever purchased, thirty-six hours after Hurricane Sandy brought a devastating surge of floodwaters into New York City. Though I had never previously thought about real estate topographically, that morning I realized I was extremely lucky. Despite the debris-strewn streets, despite the many other disruptions, I could still move because I was leaving an apartment five avenues uphill from a waterfront for one located four long blocks uphill from another. A few feet of elevation made all the difference.

While I unpacked and settled in, the writer and designer Adam Greenfield walked to a church just down my new street that had been repurposed as an aid center. There he had the experiences that led to Lifehouse (Verso; buy in the US or Canada), his new book. Subtitled “Taking Care of Ourselves in a World On Fire,” it surveys recent mutual-aid efforts and argues that, in what he calls our “Long Emergency,” “the most productive way of addressing each of the intertwined crisis that confront us” is by actually doing something about them. Not waiting for a technological breakthrough to capture carbon; not waiting for governments to pass Green New Deals; not hoping we’ll get on a shuttle to Mars. Instead, we should be “organizing ourselves to take care of one another, without waiting for anybody to issue that care to us as generic subjects, sell it to us as customers, or offer it to us as passive recipients of a charity bestowed from above.”

The long emergency we face is already here, in fits and starts, and is caused by the past few centuries’ extraction of the resources that have altered our atmosphere. “No matter what we do now,” he writes, “the combined direct and indirect consequences” of those actions “will in fairly short order exceed the capacity of our social, technical, political, and economic systems … to contain them.”

Hurricane Sandy brought this fact home to him as it did for many others—myself included. What had hitherto been news reports from tiny Pacific island nations, or even just wildfires on the other side of the US, arrived in New York with gale-force winds and a ten-foot storm surge at the tip of Manhattan, directly causing 43 deaths and more than thirty billion dollars in damage.

Activists who had participated in Occupy Wall Street in Manhattan’s Zuccotti Park the previous year stepped up to help, creating two main aid-distribution hubs, including the one near my new house. Over several months, more than sixty thousand volunteers distributed aid, dispensed medical care, cooked food, and checked in on folks across the city. They used about a million dollars in donations to buy and deliver the things people needed—sometimes creatively, as when they repurposed Amazon’s wedding-gift registry service. And they were able to do it, several later studies have shown, more effectively than Red Cross or FEMA, the federal government’s disaster-relief agency.

Greenfield suggests that, perhaps those sixty thousand people, working together and without leaders, offer “a more general template for ways in which we might organize our communities so that they shelter more of us from more of the hard times ahead.” It helps that doing so felt “healing,” that his own involvement gave him a sense of “purpose, power, and possibility.”

The book surveys other times when people came together under duress to offer each other mutual care. Greenfield looks back to the Black Panthers, calling its “survival programs” that offered things like free breakfast to anyone who needed it “the most truly revolutionary” of its efforts. He writes about Greece after the 2008 economic crash and subsequent austerity gestures, when a network of non-state healthcare outposts gave free care and medicine to all “incomers” regardless of citizenship status. He describes the “municipalist” movement in mid-2010s Spain. And through it all he locates the assembly, the practice by which people come together and decide collectively what to do with the resources they have, as the through line. One of Greenfield’s favorite thinkers is Murray Bookchin, who propounded the assembly and whose idea of “social ecology” he borrows to describe how these disparate recent movements “tend toward distributional justice.”

The example least known and most fascinating to me is that of Rojava, a Kurdish region in northern Syria. Abdullah Öcalan, cofounder of the Kurdish Workers’ Party, had found Bookchin’s writings while in prison and outlined a practice he calls Democratic Autonomy. When civil war in Syria led to a collapse of state authority in Rojava, that practice went into effect, creating what Greenfield calls “modern history’s largest-scale and longest-running example of a place where order was achieved in the absence of a state, where decisions of real material consequence were made by ordinary people sitting in assembly.”

In Rojava, these assemblies centered women’s voices, going so far as to mandate quotas for committee participation; attempted a form of restorative justice in cases of civil or criminal offense; and found ways to bring together people of many ethnic and religious communities. Crucially, these assemblies operated at micro-scale, in street-level communes wherein people knew, could trust, and felt responsible toward each other.

And it is here that the book’s title comes into play: such small gatherings, loosely federated, are how people can come together to support each other in times of difficulty. The “Lifehouse” is where this activity takes place: a building “in every three- or four-city-block radius where you can charge your phone … draw drinking water … gather with your neighbors to discuss matters of common concern, organize reliable childcare, borrow tools,” and so on. Importantly, “these can and should be one and the same place.” Greenfield suggests using churches that have lost their parishioners, commercial spaces that can’t be leased, and the like. I think of the sturdy masonic lodge in my neighborhood whose doors rarely open.

The Lifehouse concept is not only about sharing goods, but also about building up social networks, sharing skills—learning from and surviving with each other. Not every Lifehouse will have everything it needs, of course, and so they should be part of a broader network, “each one a place where people come to avail themselves of sanctuary, restoration, sustenance, and solace, each one managed and governed by the people who use it.” The infrastructure of globalization on which we depend is amazing but brittle—even a boat getting stuck in a canal can send ripple effects around the world. When interruptions happen, as they will with increasing frequency, this “wildcat infrastructure of care” will help see as many people through as possible.

It’s a compelling vision. Greenfield is ambitious about creating change, about building up resiliency in the face of the long emergency, but speaks of that ambition pragmatically. He acknowledges possible lines of criticism. Throughout, his appeal is to simply do something: “Nothing that any billionaire does will save us. If anything at all is going to save us, it will have to be us.”

Six weeks ago, large swaths of Toronto lost power after two days of torrential rain. I checked in with a few neighbors by text, but otherwise holed up in my house and waited it out, hoping the food wouldn’t spoil. So did most of the people on my block. Ten hours later, when the power came back on, we all felt double relief—of air conditioning, yes, but also of knowing that this time things didn’t go feral. After reading Lifehouse, I’m asking myself: what steps can I take to make sure my community is better prepared the next time the lights go dark?