Shop Talk

A celebrated British architect suggests ways to think about and enjoy buildings

Hi everyone,

This week, I’d like to begin with an administrative note: this iteration of Frontier Magazine will end its run on November 7.

Frontier Magazine began as an annual print publication in 2015, not long after Frontier, the studio, was founded. It served then, as now, to celebrate big ideas and inspiring people and to advance the notion of design’s ability to accelerate positive change.

We moved the publication online circa 2019, publishing occasionally through the pandemic until we launched this weekly newsletter in January 2023. Since then, we’ve sent more than 100 issues and, last autumn, released eight podcast episodes.

Frontier Magazine is not over. While this iteration of weekly stories, written by me, is coming to an end, the studio is in the process of rethinking what the magazine can be and will share more in the coming weeks. Stay subscribed to this list and you’ll be the first to know about its next iteration, with other contributors.

In the meantime, we publish! This week, a brief note on Charles Holland’s new book How to Enjoy Architecture: A Guide for Everyone and the kinds of public conversation we have about buildings. See you here next week.

As above, so below,

Brian

🔗 Good links

- 👀🏢 Buildings that caught my eye: Lluís Alexandre Casanovas’s design of an exhibition featuring Juan Muñoz’s early work; more thoughtful social housing in Paris, this time by Dechelette Architecture; Detroit firm M1DTW’s archive & gallery for the expanding Library Street Collective; Hopkins Architects’ 2018 music school in London

- 🏆🔨 Congrats to Miller Prize recipients AD–WO, who will create an installation for the next Exhibit Columbus. I interviewed cofounder Emanuel Admassu in February

- 📖📝 Friend of FM Jarrett Fuller speaks with PAU Studio founder Vishaan Chakrabarti about the books that influenced him and his work on The Architeture of Urbanity

- 🎙️⏰ Bonus round: Fuller talks with Taylor Levy and Che-Wei Wang of CW&T for the new episode of Scratching the Surface; I interviewed them here in March 2022

- 🏗️🌃 Celine Nguyen connects a new book about SimCity to tech billionaires’ attempts to build a utopian city in Solano, California

- 🔧🛜 Frontier Magazine podcast guest Erin Kissane gave a talk at the final XOXO festival in August, arguing that “we need to fix our networks.” Watch it here.

- 🏘️📈 Joshua Rosen on the housing activist Richard Wise, who watched with ambivalence as Jamaica Plain—my onetime Boston neighborhood—underwent gentrification

Shop Talk

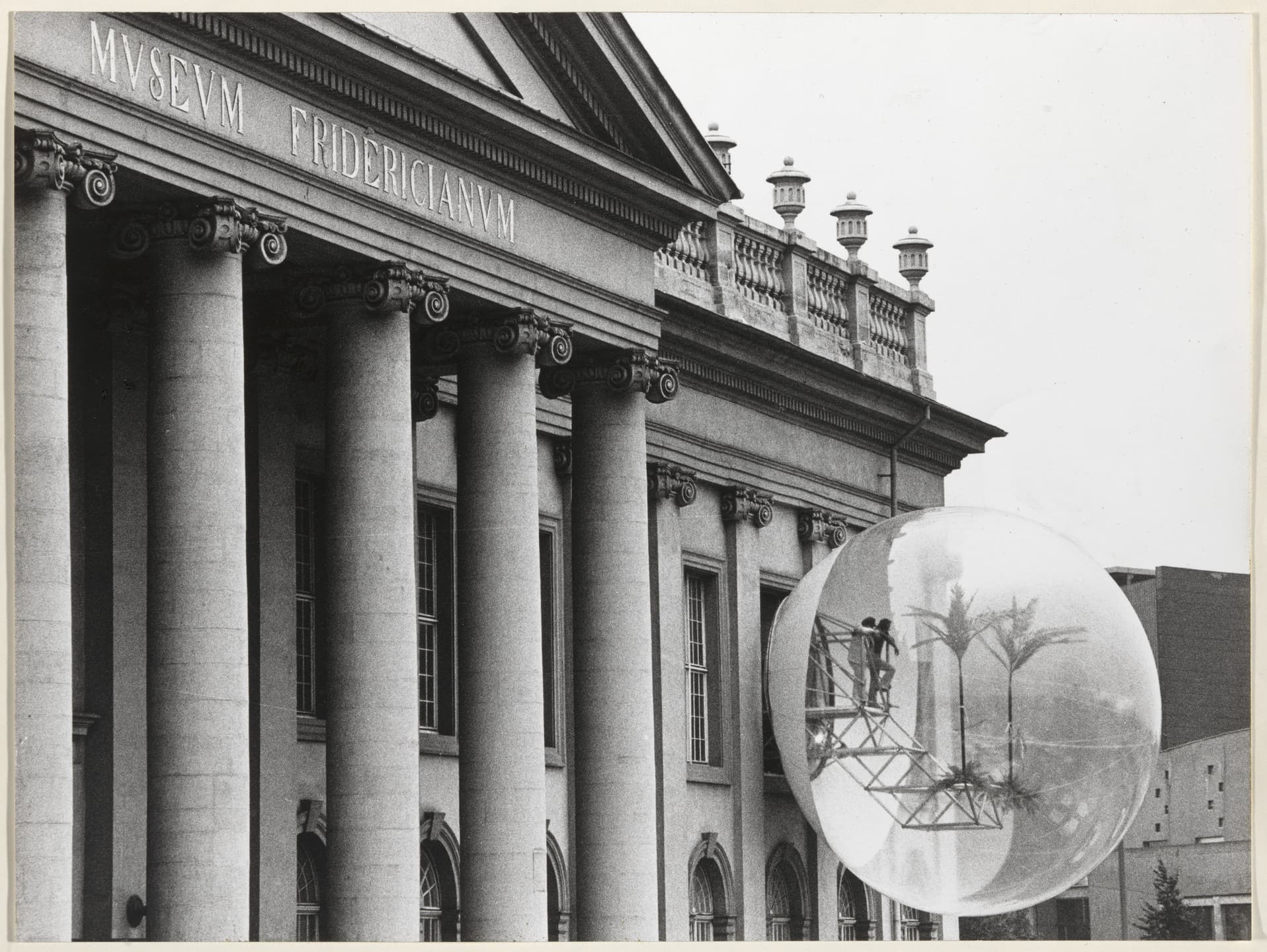

Two weeks ago, introducing an interview with someone who lives in a celebrated apartment building, I mentioned wanting to broaden the story of that midrise. Discussions of architecture are shaped primarily by the designers of buildings and those buildings’ (published) critics. I’ve had architect Charles Holland’s How to Enjoy Architecture (buy in the US or Canada) on my desk for some time, unsure of how to recommend it. But framing the aforementioned interview showed me why I find Holland’s treatise appealing.

The slim volume, with chapters on style, composition, space, materials, structure, and use, is not about Holland’s work as a partner in the celebrated firm FAT, nor subsequent projects designed while running his own studio. Instead, it’s an avuncular and idiosyncratic survey of the buildings, gardens, and places that demonstrate, for him, those six principles. It ranges from Palladian villas to a 2014 school by Spanish firm Ted’A Arquitectes, with yawning gaps in between. Holland notes early and often that the book is not a typical history, though each chapter’s introduction and conclusion has the declarative repetition of an academic study.

But in between is something I’ve had the privilege to enjoy in my own conversations with architects: shop talk. Designers talking about their own work, as in the interviews published here and elsewhere, is one thing. Architects talking about others’ work is altogether different—and often more fun.

Holland’s book, which is addressed to a general audience, is meant to inspire closer looking at the buildings and environments in which we find ourselves. To do this, he essentially catalogues his enthusiasms. The book is chatty rather than theoretical, and in it you’ll find stealthy opinions rather than zealous arguments. Those opinions are obviously informed by deep learning and a mastery of craft. Though it can be baggy at times, the book is always approachable.

It’s a paean to “the visual, spatial, and material richness of buildings without a sense of guilt as to whether it is the right kind of architecture to like,” he writes in the introduction. He’s especially good, in his chapter on composition, on how Aldo Rossi “combines not just archetypal fragments of buildings but memories, too.” And in the chapter on materials, he memorably describe Louis Kahn’s buildings as “contemporary and archaic, carrying the aloof ambiguity of inhabited ruins.” Holland also delivers a quick but useful description, in the opening of his chapter on structure, of the relationship between architects and structural engineers.

Perhaps these are figures and subjects that are known to you. Yet, as a catalogue of one designer’s encounters with buildings, even people who pay attention to architecture will find subjects new to them. For me, that was the architect Charles Voysey and the Elizabethan country house Hardwick Hall, as well as terms like the ha-ha and bungaroosh.

Some of the best experiences I’ve had with architecture were in the company of architects who could see, and explain, things I didn’t notice on my own. It’s not gossip, per se—though that’s fun, too. It’s lightly worn knowledge, freely shared. Being told how a magic trick works might diminish the surprise but not the pleasure of seeing it performed again. So, too, with the observations Holland shares in these pages. Consider this a request for more architects to write down, and more interviewers to ask about, their insights into others’ work.

§

Though it’s been twenty years since I read it, I remember feeling similarly about art—and now architecture—critic Michael Kimmelman’s 1998 book Portraits, in which he talks with artists as they amble through galleries at “the Met, the Modern, the Louvre, and elsewhere.” It seems out of print, so let me point you to your local library: find the book near you by clicking here.

More from Frontier Magazine

- Six months ago: an interview with David Godshall and Sarah Samynathan of Terremoto on creative autonomy, acknowledging labor and laborers, and building relationships that will last decades

- One year ago: an interview with photographer Mark Ruwedel about the unexpected lives of the Los Angeles River. Pictures from this body of work are on view at Gallery Luisotti in Los Angeles through November 23.

- Eighteen months ago: admitting we’re one with our technology—and doing something about it

- Two years ago: Frontier’s founder, Paddy Harrington, on the continuing relevance and value of design thinking