Stream Count

Photographer Mark Ruwedel reveals the unexpected lives of the Los Angeles River

Mark Ruwedel is a landscape photographer based in Los Angeles. He has spent decades roaming the western half of the United States and Canada, artfully documenting, in overlapping long-term series, the give and take between humans and nature. As the following conversation makes clear, he has also spent years exploring how to photograph Los Angeles itself. Beginning with projects that deliberately follow in other artists’ footsteps or were one-off partnerships with writers, Ruwedel has expanded his remit to a dizzyingly ambitious four-volume photobook series called Los Angeles: Landscapes of Four Ecologies. The first volume, Rivers Run Through It, was published last month by MACK.

Brian Sholis: The last time we spoke, about a decade ago, you were in the midst of a project that involved you walking the entire length of a Los Angeles street. I feel like you were moving west to east over dozens of miles, a journey inland.

Mark Ruwedel: A writer had invited me to join him on his own long-walk project. I stopped and started a lot—it wasn’t one long journey on foot. I thought I’d do a few pictures to accompany his story, but I got addicted to it. I kept an album of test prints, like a stamp collection. For a few years, every now and again, I’d say, “Oh, there’s a gap at mile 56,” drive out to that spot on the map, and start walking.

Some time later, Michael Mack came to visit and, in the course of showing him lots of projects, I showed him this book and my other pictures of Los Angeles and he got excited.

BS: Though I came to know your work through pictures taken across the American and Canadian west, you’ve lived in Los Angeles for a long time and have been making projects and books about the city.

MR: When I had been here several years, I wanted to do something related to Ed Ruscha. I had begun buying his photo books when I was a painting student in, like, 1978. Returning to campus after one summer, a professor had put a Yashica twin-lens camera in my mailbox. I knew that was the model Ruscha had used for his photo work.

So I started these “Ruschesque” projects, photographing apartment buildings and making visual jokes. And I began thinking about how you photograph Los Angeles. Because I spent so much time driving out to the desert or up into the mountains, my first inclination was to include all of that in my depiction of the city. It’s not the city or the country but this continuous mass of human and natural elements.

BS: Instead of a watershed, it’s like a “humanshed,” or a “human-activity shed.”

MR: Yeah. That’s probably the longest-running motif in my work, the relationship between the human-made and the natural world. And the natural landscape surrounding the city proper has unique features. One Mike Davis book says that Los Angeles has the longest urban-rural “border” of any city in the world. And it has a mountain range that goes right through the middle of it. And the mountain range is one of only two in the United States that runs east-west.

BS: You wanted to record the city in your own manner, rather than in the style of Ruscha or as part of a collaborative project with a writer.

MR: And when I won a Guggenheim grant, I had written the project up as a one-year effort. But it took a decade. This book is the first flowering of that ten-year effort.

BS: Perhaps it makes sense that it’s a ten-year project in the sense that it emerges from twenty-plus years of living in the city, of figuring out a frame. This is the first of four volumes, and its frame is essentially north to south, following the Los Angeles River watershed.

MR: Yeah, moving downstream.

BS: The first picture depicts the Big Tujunga Wash, and it’s definitely not a typical urban scene.

MR: But the very next picture includes Interstate 210, which goes to Pasadena.

BS: In the first section of the book, the city is an apparition in the distance. There’s often a little horizon line made by a highway, and then buildings beyond it—miniature in scale because of the distance from your lens.

MR: Although, technically speaking, I was in Los Angeles when I took every picture. These places are not secrets. But they’re forgotten or ignored. When I wrote the Guggenheim grant application, I talked about pictures that could encapsulate big events, but as I began doing field work I became very fascinated by these little nooks and crannies.

But also, as I was standing on that bridge depicted near the beginning of the book, I thought, “That lamp post looks familiar.” Turns out I have a movie still in my collection of Jack Nicholson standing next to one of those lampposts in Chinatown. The water running beneath it plays the role of the Los Angeles River in the movie, even though it’s a tributary. I didn’t wake up that morning seeking a spot to evoke Chinatown …

BS: It’s just that, if you’re in Los Angeles, culture is always laid atop the landscape. There’s no way to escape those coincidences.

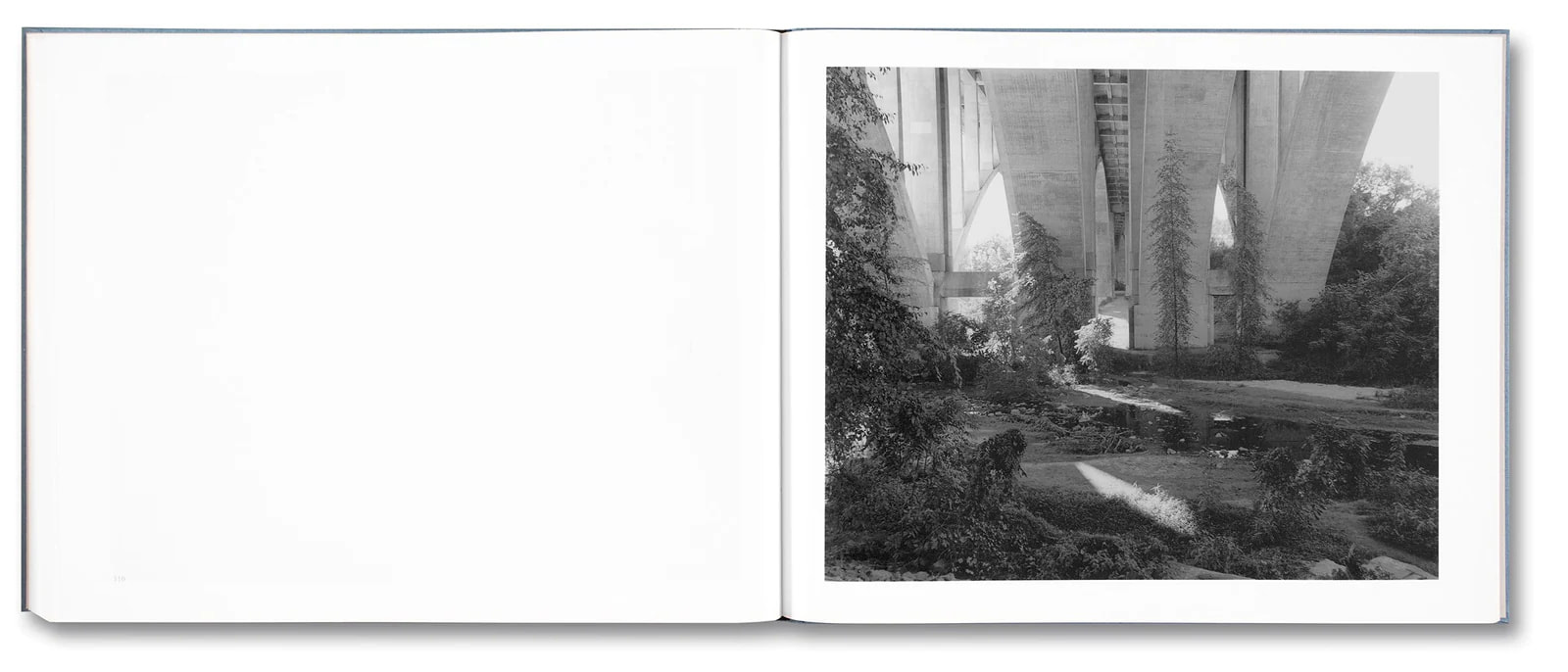

MR: Right, but the Los Angeles River in Terminator 2 is the concrete-bottom part of it, the channelized part of the river. In this book, I’ve only photographed what are called the soft-bottomed parts, with dirt and silt rather than concrete under the water. You see concrete embankments, but otherwise it’s a lot of dense brush and trees.

I was looking for surprises. I wanted to discover what I could add to the visual heritage of the river. A lot of people who live in the city don’t even know there is a river. And if you live elsewhere then you think of the chase scenes where bad guys are speeding along the concrete channel with a trickle of water in it.

BS: And a helicopter chasing them …

MR: Yeah. So I avoided all of that stuff. But I didn’t get a comprehensive view of the whole river landscape. There are tributaries that didn’t make it into the book. And anyway, every time I returned to a location, it would be different. These are dynamic landscapes, which is one possible reading of the work as a whole.

BS: That dynamism comes through in a way that I hadn’t previously grasped as an outsider: that there’s a dry season and a wet season. Four rivers cut through Toronto, where I live, but they’re just … always there. For example, the first water depicted in the book, several pictures in, is in a big plastic water jug—with the label Crystal Geyser, no less.

MR: And, ironically, Crystal Geyser is bottled out in the desert next to a dried-up lake, a lake that went dry in part because of William Mulholland’s first aqueduct, which was built to bring water to Angelenos. You can’t make this shit up.

BS: I hope I’m not reading too much into the sequencing, but that water jug is part of why I asked about the overlay of politics and culture, as is the fact that the first legible sign, off in the distance, is for the local ABC affiliate.

MR: There were several choices for that picture in the book, but I chose one with the ABC sign because I want to locate these landscapes in an urban dynamic. I could’ve just focused on trees and animals, like the heron included toward the back of the book. But I didn’t want it to be too bucolic.

You know, I also could have done a whole book of trash hanging in trees. What’s fascinating about that is how high it is—it shows how high the water goes when it’s not the dry season. That by itself says a lot about the river’s dynamism.

Anyway, I knew the water bottle was there, but I was really interested in those two boulders. They got there by the force of the water. They’ve come down from the mountains.

BS: Another word for dynamic is unstable. That’s not just earthquakes, or cultural and social fault lines, it seems.

MR: The city is a geological anomaly, without even getting into plate tectonics.

BS: You say that Los Angeles is the best place in North America from which to explore and try to understand the tension between the “human-made” and the “natural.” You explored those tensions across the West for decades, and now you’ve found them closer to home.

MR: Though I love the city, it wouldn’t be possible to conceive a project like this in Montreal, for example.

BS: We’ve gone this long without even mentioning Rayner Banham, whose 1971 book Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies inspired the title for this four-volume photobook project.

MR: I’m not sure how that book’s title popped into my head. I hadn’t read it in forever. But when I was coming to terms with what I wanted to do here, I settled on these four frames, four landscape ideas, and that somehow triggered it. Once I made the connection, I reread the book. And I actually found it really frustrating. It feels naive, a gleeful celebration of the worst parts of the city. He had no interest in the landscape; he only mentions the river once.

Do you know the art critic Peter Plagens?

BS: Yes.

MR: He wrote a rebuttal to the Banham in Artforum that’s more in line with my stance. His essay and Mike Davis’s Ecology of Fear are more in tune with my thinking about this project.

BS: A final question: you live in Long Beach, which is where the river washes out into the ocean. If your earlier project, with your writer friend, was a journey inland, is this book in some sense a journey homeward?

MR: Strangely I’ve never thought of it that way, even though two of the final pictures in the sequence I made while out walking my dog, just six or eight blocks from here. This is the point where the freshwater meets the sea. And, of course, the current configuration was made not only by nature but also by the Army Corps of Engineers.