Survival Stories

The narrative infrastructure that makes brands and cities work

In 2007, a developer decided to build a housing estate in Xingqiao Subdistrict near Hangzhou, China and attract interest and residents through its unique approach to design. The central feature was a 108-metre tower in the middle of an open plaza. The tower was a replica. The original, three times the size of this copy, was a famous tower on the other side of the world, in Paris: the Eiffel Tower.

The replica sits at the heart of Tianducheng, which is itself a replica of Paris. A residential district, the avenues that radiate from the core are lined with neoclassical buildings and Baroque-style fountains and statues. Those who have been there, including Parisians, remark on moments of uncanny likeness to the source of inspiration.

Designed to accommodate ten thousand residents, the initial occupancy was estimated at two thousand people in 2013. While the reasons for the lack of inhabitants are many, it’s fair to say that the visually striking replica remained largely empty and culturally sterile because there it carried none of the embedded narrative infrastructure contained by Paris.

The Mecca of Stories

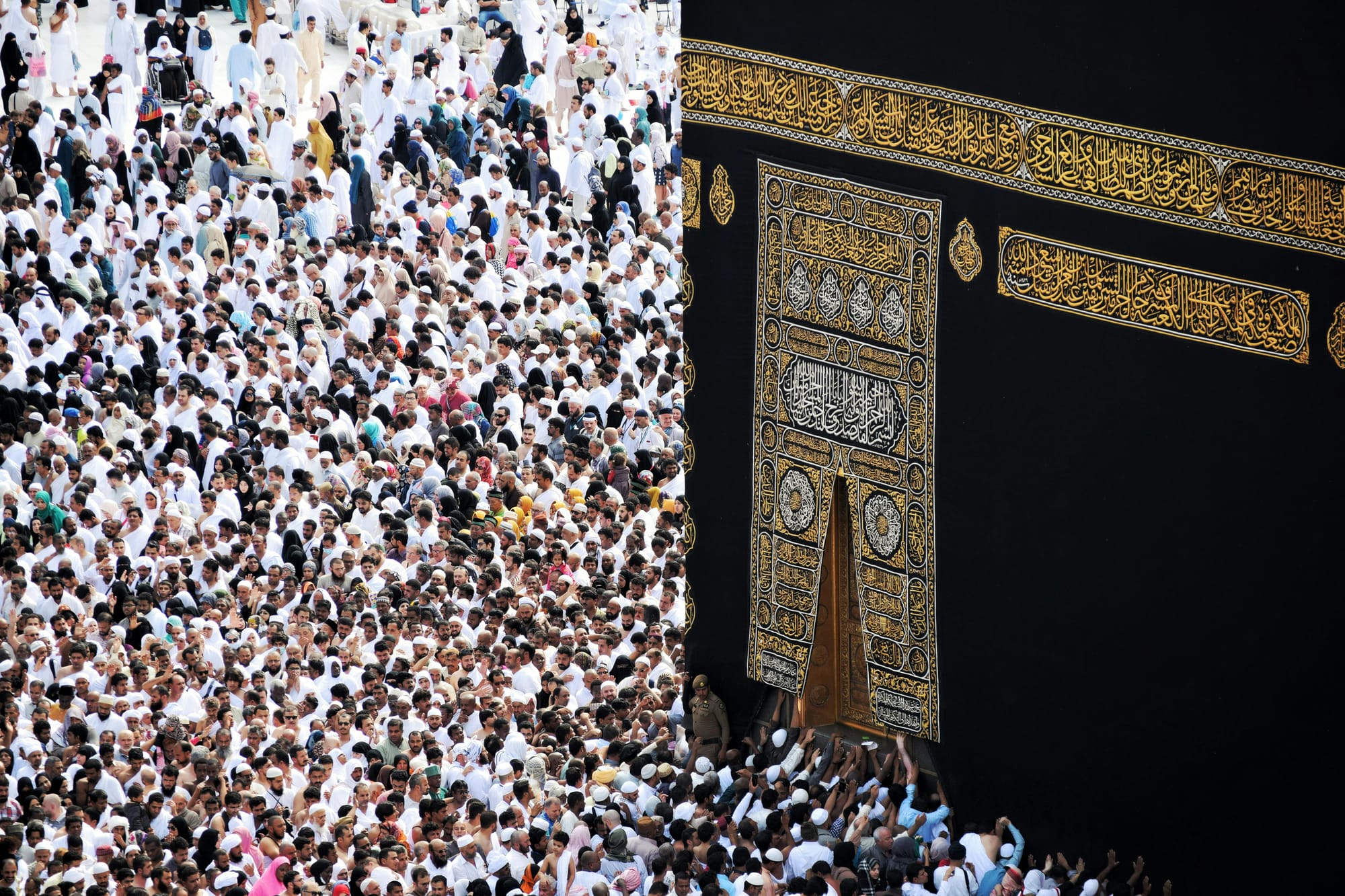

In 2008, Bruce Mau Design was chosen as one of about thirty international design teams to work on a new vision for the Holy City of Mecca in Saudi Arabia. At the time, over two million Muslims performed the Hajj pilgrimage every year.

The pilgrimage lasts five to six days during the Islamic month of Dhu al-Hijjah and follows a precise sequence of sacred rites in and around Mecca. Pilgrims first enter a state of ihram and wear simple white garments before circling the Kaaba, walking between the hills of Safa and Marwah, standing in prayer on the Plain of Arafat, spending the night under the open sky in Muzdalifah, and symbolically stoning pillars representing the devil in Mina. The experience culminates in the Eid al-Adha sacrifice and a farewell circumambulation of the Kaaba.

In 2025, about 1.67 million people performed these rituals over the course of the pilgrimage, meaning roughly 334,000 people per day converged in the compact area, smaller than a football field, at the heart of Mecca. To grasp the scale, it’s comparable to the density and energy of New York’s Times Square on New Year’s Eve, which draws around a million people for just a few hours, except sustained for nearly a week in extreme desert heat. It is also the daily equivalent of holding multiple March on Washington–size gatherings, each over 250,000 people, for five consecutive days, in a tightly confined space.

The visioning project was not conceived on the basis of religious need. It was an engineering problem. Over the years, hundreds of people had died during the pilgrimage, largely due to cardiovascular issues caused by the compressed crowds moving in and around the space. Officials recognized they needed a new way of thinking about the logistics.

The overall master-planning project was divided into parts. The largest set of teams, a roster of international superstar design firms along with leading local and global universities, focused on ways to expand the site and make the Grand Mosque more efficient. Five international infrastructure and engineering firms were tasked with creating plans for transportation into and out of the city centre, and our team was given the role of creating the “vision plan” for the project.

That role was to tie the project together by creating its narrative infrastructure. The work was not simply telling a story about how Muslims would take part in Hajj; instead, it was the driving framework for organizing the urban-design approach. A hybrid drawing upon the principles of urban planning, key themes in Islamic faith, and the fundamental transcendental experience of the Hajj came together in our work, which was grounded in meaning, symbol, and ritual.

Narrative Infrastructure for Cities

Tianducheng and Mecca are remarkable for different reasons. Tianducheng is a simulation. It’s the quick imposition of a known identity, Paris, onto a part of China previously unoccupied by people. Mecca has had continuous human influence for at least three thousand years, with religious significance traced in Islamic tradition to Abraham and Ishmael, and by the sixth century CE it was a major trade and pilgrimage centre. There are thousands of years of human presence, culture, rituals, stories, and symbols that have given it meaning beyond its physical form.

This invisible network of elements is just like the underground utilities of a city. But where physical infrastructure makes a city livable, narrative infrastructure makes it lovable.

Superkilen Park in Copenhagen contains cultural artifacts from local immigrant communities embedded into the physical space. Designed collaboratively by BIG (Bjarke Ingels Group), Topotek 1c, and Superflex, the park is filled with more than one hundred artifacts sourced from or inspired by the diverse immigrant communities of the surrounding Nørrebro neighborhood, turning the park into a catalogue of global culture.

A Moroccan fountain and a Pakistani bus stop sit alongside a neon sign from a Moscow butcher. A Thai boxing ring shares space with soil imported from Palestine. Play areas feature a Japanese octopus slide and swings from Iraq, and public amenities include a Texas barbecue grill, a Spanish concrete ping-pong table, and Brazilian benches.

Even the ground bears cultural markers, with patterned Somali manhole covers embedded into the pavement. Together, these elements transform the park into a physical, walkable archive of the neighbourhood’s many origins, blending recreation, art, and cultural heritage into a single urban landscape.

More broadly, narrative infrastructure is the layer of a city’s design that encodes and communicates the shared stories of its people—not as a static tribute to the past, but as a living framework that shapes how residents and visitors understand, use, and belong to a place.

In Medellín, Colombia, the Parque Biblioteca España redefines civic infrastructure by combining library and park functions in underserved neighborhoods, designed with community input and infused with local cultural motifs. These complexes are not monuments to what was, but active hubs where education, leisure, and identity converge daily.

In Melbourne, Australia, Federation Square blends contemporary materials with Aboriginal art patterns, making Indigenous heritage a visible, integral part of a central gathering place.

Milan’s Garden of the Righteous Worldwide transforms remembrance into participation, honouring global defenders of human rights through a landscape of trees, not statues, which means the memorial is tied to cycles of growth rather than static symbols.

Singapore’s Little India Heritage Walk threads murals, sculptures, and outdoor furniture into the streetscape, making cultural identity an everyday encounter rather than an occasional festival.

In New York, the Queens Museum’s Corona Plaza embodies the diverse immigrant roots of its community through co-designed seating, paving, and public art, embedding cultural origins into the physical space of daily life.

And in Ottawa’s ByWard Market, large-scale murals weave together languages, symbols, and stories from the area’s multicultural vendors, turning a commercial district into an open-air archive of its people.

Across these examples, narrative infrastructure works not by preserving cities in formaldehyde, but by using design as an active, evolving medium for belonging, memory, and shared direction.

Narrative Infrastructure for Brands

Narrative infrastructure works in brands much the same way it does in cities. Cycling apparel company Rapha’s power lies in the shared rituals its Cycling Club fosters. Members don’t just buy jerseys; they participate in organized rides, gather in clubhouses, and connect through a global calendar of events. The story of elite cycling culture is baked into every interaction, creating a sense of belonging that far outlasts the purchase of one of its classic jerseys.

Aesop takes a different approach, embedding narrative directly into place. Each store is designed as a one-off that reflects the architectural history and cultural cues of its neighbourhood—a location in Kyoto may be lined with cypress, while a space in Los Angeles might channel mid-century modernism. This hyper-local approach turns shopping into a form of cultural engagement, where the physical environment reinforces the brand’s values of care and detail along with its sensorial approach to design.

Monocle operates less like a magazine and more like a worldview you can live in. Its cafés, retail spaces, and events create a lifestyle infrastructure around the editorial voice, allowing readers to live inside the brand’s narrative of global curiosity and refined taste.

In each case, the brand’s products, logos, interiors, and other elements are supported by a deeper network of stories, rituals, and symbols. Just like cities, brands with strong narrative infrastructure become more than the sum of their parts. They’re not simply consumed; they’re lived in.

Putting Principles to Action

Designing narrative infrastructure starts with recognizing and amplifying what already exists. The strongest stories are the ones people are already telling. In Margaret River, Australia, the vineyards and surf breaks are not just tourist attractions but the backbone of a lifestyle brand. Wineries host surf competitions, and surf shops stock local vintages. This crossover makes the narrative feel lived, not manufactured.

From there, it’s about creating or reinforcing rituals: repeatable, communal experiences that anchor meaning in time and space. Park(ing) Day, which began in San Francisco in 2005 with a single metered parking space transformed into a mini-park, now happens in cities from Tokyo to Cape Town, inviting people worldwide to see their streets as public living rooms.

Creating symbols also matters. They serve as visual or tactile shorthand for a larger story, making it instantly recognizable and easy to recall. Glasgow’s “People Make Glasgow” campaign, with its bold pink plastered across buses, banners, and the city’s skyline, acts as both a civic pep talk and a tourist welcome sign.

Finally, narrative infrastructure thrives when it’s co-authored. When residents shape the story, it becomes rooted in their lives. In South Central Los Angeles, Ron Finley turned the strip of neglected dirt outside his home into a thriving vegetable garden—sparking a movement that inspired neighbours to do the same. What began as one person reclaiming public space grew into a shared, living narrative of self-reliance, beauty, and community pride.

Together, these principles turn infrastructure into identity, and place-making into story-making.

Stories Find a Way

Despite the initial struggles of Tianducheng, it slowly found itself.

In 2023, Canadian digital media brand Yes Theory created a YouTube video called “I Explored China’s Failed $1 Billion Copy of Paris (real city).” While initially skeptical, they slowly discover a surprisingly lively culture. It turns out, by 2017, its population had grown to thirty thousand; the development has been expanded several times. The city had built its own unique narrative infrastructure out of its origins as a copy.

The park under the Eiffel Tower replica is undergoing construction into a commercial area, due to be completed in 2027, and it has even turned up in a music video by Jamie XX, who filmed the video for “Gosh” against the backdrop of the strange city.

Cities are, perhaps, the greatest human achievement. There is no more resilient invention. We’ve mastered the art of building streets, towers, and transit systems. But the most successful cities, those that own a place in our consciousness, are far more than the sum of their infrastructure. The same is true for brands. Those that endure, that become interwoven into our culture, are alive with stories, rituals, and symbols. Whether old, new, or future, there is value in designing narrative infrastructure; the invisible stories that make great cities and great brands matter.