The Frontier Interview—Brock James on designing libraries

The Toronto architect discusses the imperative of flexibility, fostering community, and responding thoughtfully to existing contexts

Hi everyone,

The rain that incapacitated much of Toronto on Tuesday fell a week after the remnants of Hurricane Beryl passed through. Four inches in four hours, yes, but us and our choices are why it had the impact it did. My neighborhood lost power for ten hours; I picked my kids up from summer camp by navigating community-center hallways with my phone’s flashlight.

As our climate gets harder, we can do better, and one of my favorite responses came from my pal Stefan Novakovic, who made sure to not only lament political and design inadequacies but also to point to half a dozen efforts—across the globe and elsewhere in Canada—our city can use as models.

As Deb Chachra, a guest on the Frontier Magazine podcast last fall, put it so aptly: infrastructure is “care at scale.” So this week, alongside this acknowledgement that we can do more to care for our landscape, our buildings, and our neighbors, a celebration of some infrastructure we’ve gotten right: the design of two recent Toronto Public Library branches in Scarborough. Below you’ll find an interview with Brock James, a partner at LGA Architectural Partners, the firm behind the Scarborough Civic Centre Branch (2015) and the Albert Campbell Branch (2022). For readers in Toronto: they’re both worth a destination visit.

Until next week,

Brian

🔗 Good links

- 🏢👀 Buildings that caught my eye: BGY repurposes an ice factory in London; Gardiner Architects’ off-grid home in rural Australia for an artist & teacher; Pihlmann Architects’ renovation and expansion of a kunsthalle on a small island in Denmark; Fictional Project’s multistory brick art studio & home in Chennai, India

- 📚🏘️ Michael Kimmelman: “Library systems have become some of [The United States’] most venturesome patrons of new architecture.”

- 🇯🇵📬 Apropos our recent issue about Tokyo, here’s London architect Mike Stiff with some notes on new buildings in the city

- 🌆🌆 “What can you learn about a city just by looking at images of how it has gradually changed over time?” An interview with the creators of Sunset Over Sunset.

- 🎰📖 Denise Scott Brown reflects on the original design of Learning from Las Vegas: “for Muriel [Cooper], ‘radical’ meant the revolution previous to ours.”

- 🔎🪚 Is physical model making in architecture a dying art?

The Frontier Interview—Brock James

Brian Sholis: Both buildings respond to early-1970s precedents, whether through direct renovation or through adjacency. Obviously there are differences between that high-modern/Brutalist moment and today, but I thought we could begin by discussing those differences in terms of civic architecture. What messages did those existing buildings try to convey, and what, if anything, is still considered valid about that era’s design approaches?

Brock James: One thing that unites the two contexts we worked in—the south side of the Scarborough Civic Centre and the existing Albert P. Campbell library branch—is that their facades feel closed. That doesn’t align with what libraries want to be now. They want to be porous. They want to influence their surroundings and be influenced in turn.

On early visits to Albert Campbell, I was reminded of Toronto’s Reference Library, which, like Scarborough Civic Centre, was designed by Raymond Moriyama. It had an internal space suffused with natural light but didn’t really offer direct views of the outdoors. Once you’re inside, it’s calm, almost as if you’ve been separated from the urban context—the buildings were, in some way, a kind of escape.

That stance isn’t appreciated these days, but I’m glad you asked about what’s still valid. Because today, the kinds of floor-to-ceiling windows that design culture prized only ten or fifteen years ago are no longer as celebrated. So one thing that Fairfield and DuBois got right was the window to wall ratio. We pushed that a little bit, to make the building feel more connected and open to its surroundings, but for energy purposes we knew we didn’t want to open it completely. It was interesting to see how they got daylight into the library without a well-insulated, high-performing envelope.

Times change, priorities change. When Toronto Public Library leadership first talked with us about the project, we talked about connections both outside and within the building. Within the building, you could look down from upper floors and see your way down, but it was harder to have that sense of connection when you were on lower floors looking up. So that was one thing we worked on.

BS: I noticed that on my visit to the building, and will return to it. But to stay with libraries more generally, I think your discussion of libraries being “open to influence” is a gentle way of saying that, by necessity, they now offer so many services to their communities and fulfill social needs that used to be addressed elsewhere in the urban environment. Do such changes impact the architectural requirements of these buildings?

BJ: Librarians and library branches do indeed have an evolved mandate, one that has a broader definition of equitable access. Today we better recognize how important they are as public spaces. One thing I think is less appreciated is that the space of a library is itself so important for giving communities a sense of identity and connection. This is a video call, and it’s pretty good, but we’d both agree it’s not the same as being in the same place, talking face-to-face. So, too, with access to information. The internet is great, but I think we’d also both agree that such access is even better when connected to a space where we can also be with friends or others who share our interests, who have overlapping concerns. Grounding access to information in a place and a local community is one of the unique values of branch libraries.

We designed these two Scarborough branches with that idea in mind. There are places within each that allow you to connect with others, in a multitude of ways. At Albert Campbell, for example, the largest room, downstairs, can have more than a hundred people in different configurations—and they can be seen from elsewhere in the building.

BS: You’re right that we agree on the broader point, and I’d say that in addition to mixing information access with the serendipity of social encounters, even just seeking information on shelves offers greater serendipity than search results. I’d like to turn to the Scarborough Civic Centre branch, which was built from the ground up to prioritize the kinds of flexibility you describe in the largest Albert Campbell room.

BJ: They’ve held weddings in there …

BS: Even the bookshelves are on wheels, and the building has one level. Can you talk about those decisions?

BJ: Well, both projects are a lot about the roof and ceiling. At the Civic Centre, we created an extremely flexible floor plate, one that’s even raised so you can easily access and rearrange, for example, the power outlets. That necessitates a kind of neutrality. But our roof didn’t need that, and so we used it to be site-specific, to add personality. We think of Moriyama’s Civic Centre building—this big, imposing white structure—as being akin to the nearby bluffs on the lake. So we treated our roof as being akin to the shoreline.

The other quality of the Civic Centre is that … well, it’s the civic centre. So while I’m contradicting what I said earlier about not using glass walls—and that’s OK, we all evolve, it’s natural—it was important then for us that each side of the library connect to the unique things around it: the green, the street, Moriyama’s building, the plaza. Each has its own energy.

Librarians—more specifically urban librarians, and TPL librarians in particular—get new ideas from working with their communities. Every few years they have new thoughts about how their offering should evolve. It makes sense: if you’re hooked into a community, that community will change, and so will its needs. So we tried to give them a building that could evolve with them.

BS: Let’s return to my experience of Albert Campbell. You talked about the interior feeling “connected” from only certain vantage points. You inherited a lot of concrete. How did you decide where and how to intervene to create that greater sense of connection?

BJ: The concrete is a clear span with columns, so it was pretty flexible—though, for reasons not worth getting into here, it wasn’t very easy cutting into it. We had to take care to reinforce the existing structure. The whole thing took careful study.

Our first big decision was to move the entrance from the second floor down to the lower floor, which in the original design was mostly not open to the public. We weren’t sure it would work and had to lean on some essential principles of spatial perception to help. So there’s the classic Frank Lloyd Wright compression-and-release, with a low entry that then opens up above you. And if you look all the way through the building, at the back, opposite the entrance, is a window.

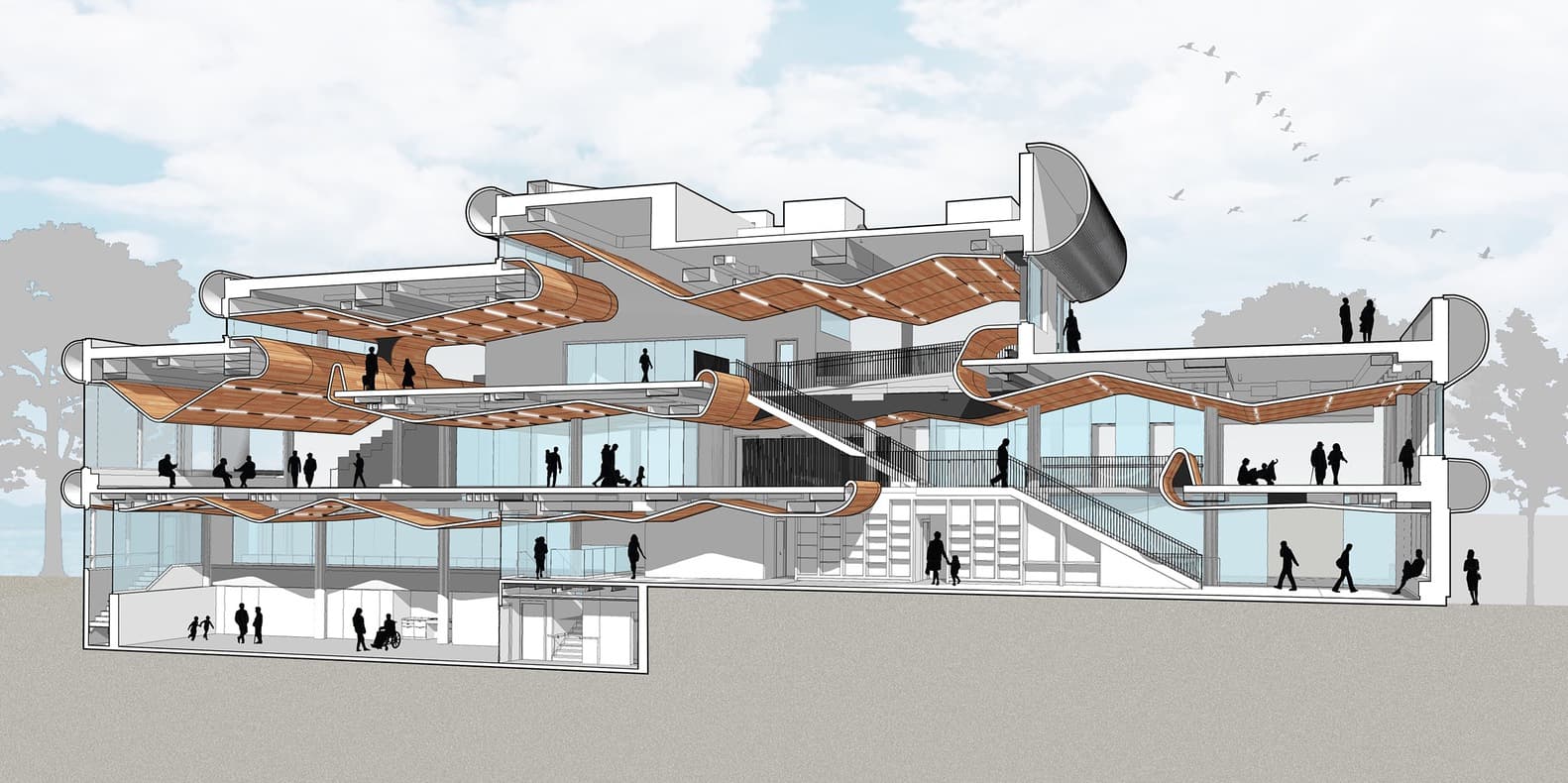

Elsewhere, we again aimed for flexibility. We put in some laptop counters, some small meeting rooms, some tables on a higher floor that both can be pulled together for a bigger gathering and look out onto a terrace. You can have people reading behind you, others working to your left, still others going up and down the stairs. And above it all, there’s an undulating wood-covered ceiling that is sometimes closer and sometimes further away from you.

BS: The building feels more spatially complex than perhaps it actually is, in that the cut-throughs and the views gave me the sense of intermediary levels, landings in between floors.

BJ: Yes, there are many vantage points. And some of that also comes out of other work we’ve done. For example, we’ve built a lot of transitional housing for nonprofits. In those contexts we talk about thresholds and shelters, places where you can engage the community or withdraw a bit. That flexibility helps people transition to a greater sense of stability on their own terms. And the lessons from that work apply to libraries and other public buildings, too.

BS: The other big decision we haven’t really touched on is that TPL’s original plan for the Albert Campbell branch specified either expanding or demolishing the existing building. While I presume carbon is part of it, can you discuss your reasons for preserving the original?

BJ: To be honest, part of it is the site-plan approval process in Toronto, which can be pretty time-consuming. That gives keeping the footprint an advantage. And keeping the status quo, in terms of surface porosity on the site, helps with stormwater—something that’s fresh in mind as we talk.

Albert Campbell made it easy because while it was hard to love from the outside, as soon as we went inside we were inspired—it got on our good side. We thought, “Wow, let’s try to move with this energy.” And, of course, you’re right about carbon. If you’re giving it any kind of weight in your design process, then the responsible decision is to make reuse your first priority.

All these things make it important to be more accepting of what’s there. Over time, our firm has adopted that sensibility. We are glad to find the path that yields something great out of existing conditions. It feels like we’ve added a layer to Albert Campbell, and I can imagine a scenario where in thirty or fifty years somebody’s going to change what we did. It’s the way of the world, and we’re comfortable and happy to be working with existing conditions, getting the energy from that, and making the best buildings we can.

BS: It’s an architecture of stewardship—and a willingness to be stewarded in turn.

BJ: And it’s not a “compromise” if you do it right. It takes more care, more analysis, more effort, more persistence. But it’s worth it and seems especially appropriate for libraries. Part of what makes librarians and branch libraries great is they take on that responsibility of working with what they’re given and doing the right thing. We all can learn from that.