The Frontier Interview—Common Accounts, “The Death Report”

Igor Bragado and Miles Gertler rethink architecture’s relationship to the inevitable

Hi everyone,

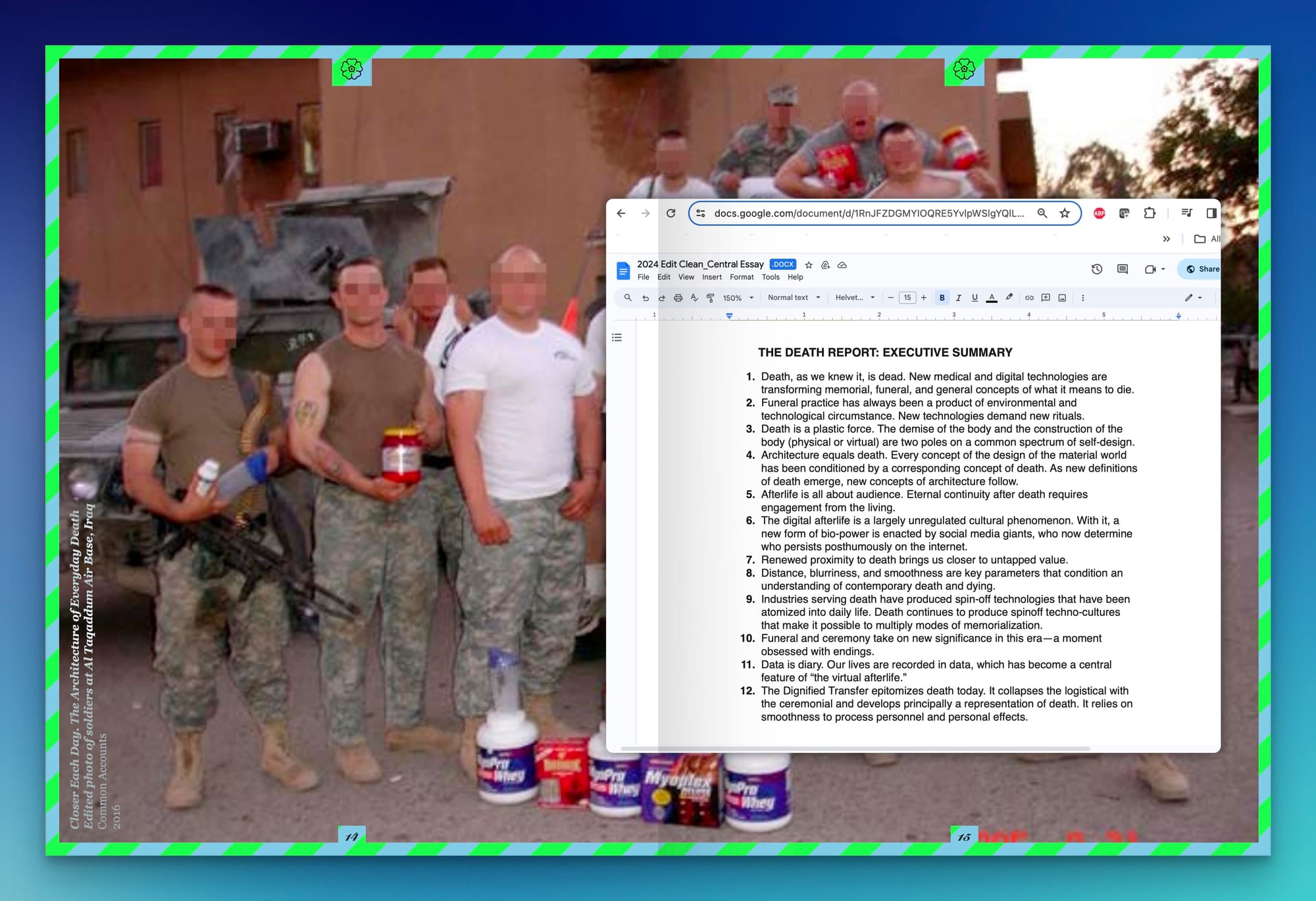

This week, an interview with architects and researchers Igor Bragado and Miles Gertler, who together form the experimental design studio Common Accounts. Last week they released The Death Report, an anthology of writing and design projects that examines the “deep history and near future” architecture’s relationship to death. Below this week’s links, we discuss why death has receded from the architectural imagination, the difference between rituals and spectacles, and how rapidly evolving technologies give designers ways rethink our relationship to the end of our lives.

As always, I’d love to hear from you—reply to this email or comment below.

Until next week,

Brian

Two takeaways

- Out of sight, out of designers’ minds: Over the past 150 years, as health regulations and changing social mores pushed death to the edges of both cities and our attention, architects and designers began to neglect death as a subject worthy of design consideration.

- New technologies, new rituals: Rapidly evolving technologies are reshaping how we think about, come together around, and memorialize deaths. These new rituals also offer opportunities for designers to intervene and create social, ecological, and other forms of value.

🔗️ Good links

- 👀🏢 Buildings that caught my eye this week: Studio Wok’s minimal funerary house; Prokš Přikryl Architects’ grain-silo renovation (drawings, photos); Office MI–JI’s 2021 house in Barwon Heads, Australia

- 🗑️♻️ In The Walrus, Christina Myers asks, “What should you do with your stuff before you die?”

- 🇯🇵📉 “Why half of Japan’s cities are at risk of disappearing in 100 years”

- 🛻🤑 On the Montreal politician increasing parking fees for SUVs and big trucks

- 🏘️🏘️ “Sprawl is a pattern of development, not a location. Sprawl is a product, not a place.” A thorough Declaration of Independence from Sprawl.

The Frontier Interview—Common Accounts, “The Death Report”

Brian Sholis: The cliché has it that the two inevitable things in life are death and taxes. Architects and developers know how tax laws, like California’s infamous Proposition 13, shape what gets built or not built. One of your arguments is that architects and designers have less appreciation for how death can be—or already is—a design issue. Can you elaborate on that?

Miles Gertler: The condition you’re pointing to, the distance of death from the radar of the design disciplines, is recent. Historically, death has been a canonical arena for design activity, from pyramids to mausoleums in cemeteries; in the report, we say that every theory of architecture is conditioned by a theory of death. Those subjects have always been coupled.

But modernity distanced death from daily life, generally speaking, and with that we’ve surrendered the idea of death as something that benefits from design and consideration.

Igor Bragado: One of the report’s goals is to consider why that happened and to measure that distance. Sometimes it’s literally measured in kilometers, as when local butchers became largely replaced by slaughterhouses on the edges of cities. At other times it’s a conceptual distance measured in blurriness or (in)visibility. Our point of entry is Sigfried Giedion’s 1948 book Mechanization Takes Command, which features a chapter on death written in the wake of the two world wars.

BS: He’s writing at a moment—and in a place, Europe—where human death has just been industrialized.

MG: Today we do not think as intensely about the material business of death, the material disposition of degrading organic matter, and how it is part of rituals. And we certainly aren’t thinking about how death can better serve society; one of our main arguments is that a renewed proximity to the fact of death might yield ecological, material, and social value.

IB: In the modern movement, a house was meant to be a machine for living in, right? Architects became obsessed with a healthy subject; death and its related conditions were evacuated from the house, from our cities, from our ways of thinking.

MG: Death serves as a kind of proxy for so many things society fears: illness, old age, ability. It’s important we don’t let these concerns be marginalized from mainstream social discourse.

BS: We shouldn’t go too much further without articulating your definition of death. There are three parts: the anatomical, the social, and the digital.

MG: It is as important to identify these domains in which death can be enacted or delayed or sustained and drawn out. And everything about them is up for continual renegotiation. In the 1970s, Lyn H. Lofland began to outline the changing biological nature of death: advances in medicine meant we lived longer with terminal illnesses, for instance. Today, the sense of a life’ “duration” or an “afterlife” has changed thanks to the digital realm, and especially social media. That’s one space where death has come to the fore and yet there has not been significant thinking about the design of those experiences.

IB: Those three categories are important for us because architecture has historically approached death from a metaphorical or metaphysical plane; take, for example, Aldo Rossi’s San Cataldo Cemetery. But each of these three categories—the anatomical, the social, and the digital—has its own material conditions and generates its own physical outputs.

BS: The life extension that Miles refers to also leads to a blurring of the boundary between life and death itself, and I wonder if the spatial distancing you talk about happening a century ago is paralleled, socially, in the “pushing off” of death through medical intervention. The “terminal” disease is no longer always terminal, and declines are always managed medically.

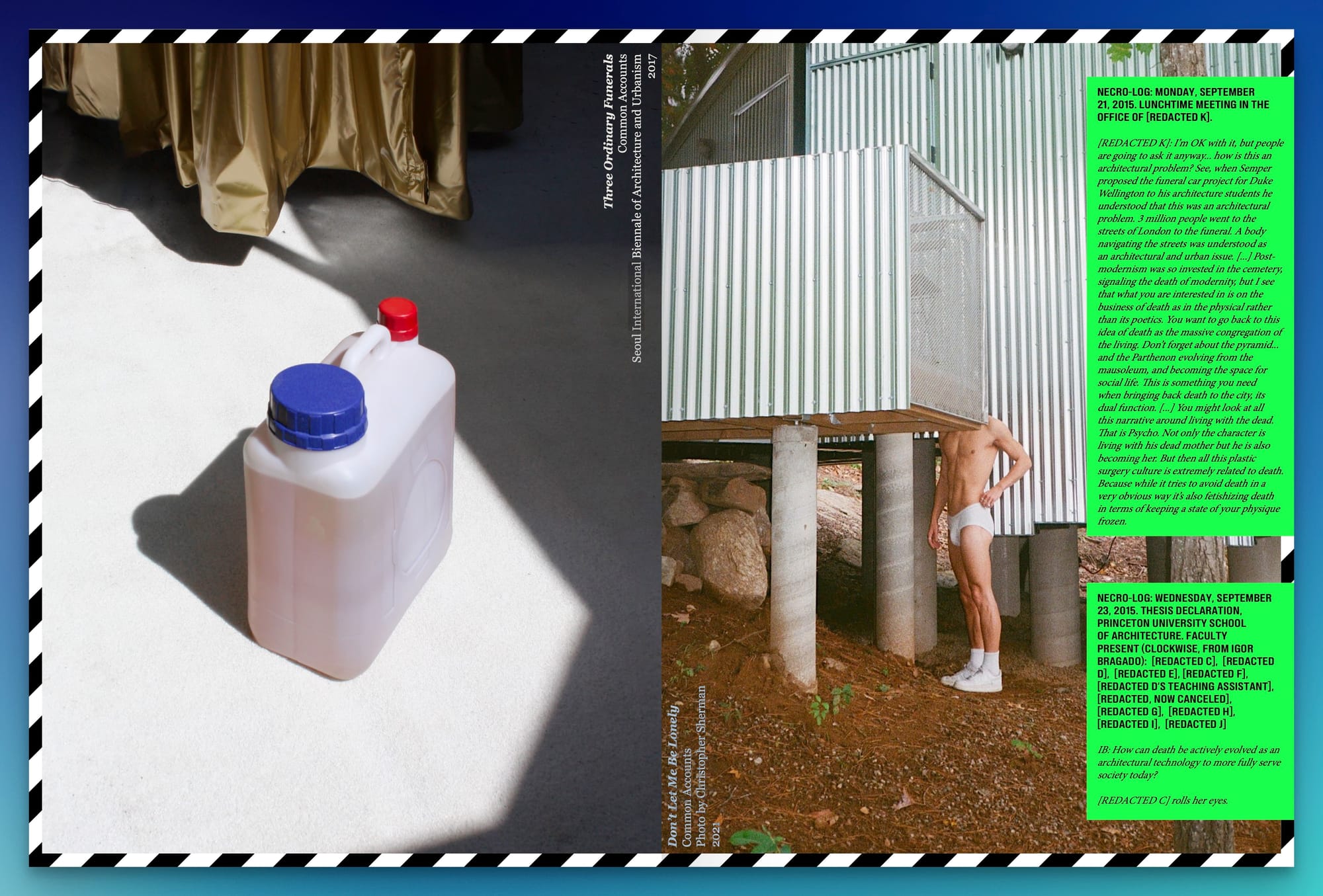

MG: Absolutely. In fact, our project Three Ordinary Funerals, which was a prototypical funeral home that we built in Seoul in 2017, investigated a century’s worth of funeral cultures in Korea. Over that time, the funeral industry was partly absorbed into the healthcare industry, with rituals moving from the physical and social spaces of the courtyard house and the neighborhood into hospitals. Our design was a kind of prosthetic attachment to a traditional Hanok courtyard house that we suggest could enable new, different, and more constructive rituals.

BS: Rituals and ceremonies run through the report. As I read, I began wondering what are the boundaries of rituals, what distinguishes them from spectacles? Perhaps a spectacle is a ritual we can only watch and not participate in …

MG: That’s interesting. At one point our editor Charlie Robin Jones asked us, “Who was the last really famous person that died?” It took us a second, but we settled on both Matthew Perry and Queen Elizabeth. Those two deaths were both spectacles but constructed their audiences in different ways.

The queue along the Thames to visit the Queen lying in state in Westminster was a spectacle itself. The funeral had its own design, but the queue created another center of gravity; the BBC even created a weather report for the line.

IB: Spectacles require some degree of exceptionality, right? They are something unexpected, something that hasn’t been repeated, like a ritual. Our report includes examples of both. It’s difficult to navigate these two poles of the exceptional and the common in contemporary rituals because technology is evolving so quickly—a small ritual can become a viral spectacle; a spectacle can be copied so quickly that it becomes a ritual.

And, for example, there isn’t a long track record of how people share images and videos from funerals on Instagram Stories. We made a point of looking at ordinary or quotidian conditions that are being overturned by changes in technology or social mores.

BS: We’ve talked about your research, but thus far you’ve only referenced one of your design projects, in Seoul. Tell me about how working both as writers and designers expanded your thinking about this subject.

MG: We belong to the long tradition of architects working in the Learning from Las Vegas mold, the academic research studio. We also feel kinship with Jack Halberstam’s low theory; we want to engage low and high culture, build eccentric bibliographies. At the same time, we create designs that test our theories, especially those we’ve developed around death and funerals. We engage with unresolved situations, things that haven’t resolved into neat conclusions. This engagement shapes our thinking.

IB: We also examine how history—in this case, historical rituals—is reframed by contemporary developments.

BS: Yet the result isn’t what you’d see in a journal of architectural history. This report is a PDF with bright colors, varied typography, and a collage aesthetic.

IB: I like to think of what we release, whether projects or texts, as a byproduct of our relationship. We absorb and talk about everything: buildings, history, memes, pop songs. Everything gets in, and we hope for our buildings and installations to also work as platforms that, in holding multiple inputs, can foster multiple conversations. In doing that, we kind of code-switch: sometimes a text appears in a traditional journal, as you note; other times they can look like corporate trend reports. We can be serious, we can be joyous.

MG: At the same time, since we want to encourage a closer proximity to ordinary death, we decided we needed to change the tone of the conversation. We don’t think death has to be feared, and packaging the report in this way sketches it as something improvisational and animate and vital.

BS: As a final question, do you have wills or end-of-life directives for your loved ones?

MG: Embarrassingly, not yet! Perhaps you can notarize this transcript?

BS: I’m not sure that’s an option in Google Meet’s settings.

MG: But perhaps it’s the next frontier for us to consider. Architecture, as an industry, is almost entirely oriented around providing instructional documents. I will say that our work on death has been largely analytical and representational. Perhaps the next step is for it to become more instructional.

IB: Or we could simply say that the death report is itself our will and testament.