The Frontier Interview: “Where Is Africa” with Anita N. Bateman & Emanuel Admassu

On representations of the continent—who gets to make them, how they circulate, and what they mean

Hi everyone,

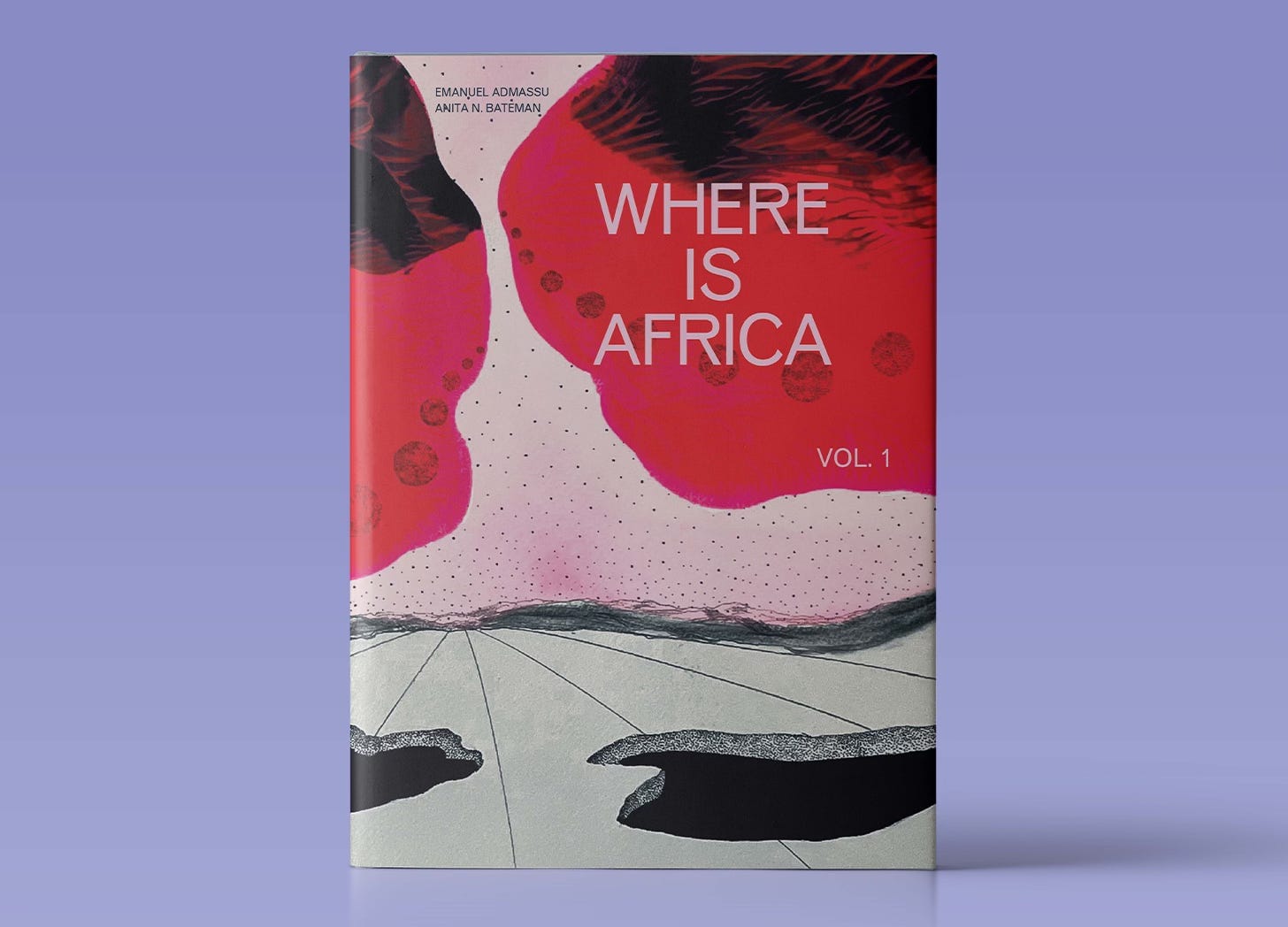

Where Is Africa is a new book that intersperses long-form interviews with artists, architects, and academics with commissioned artistic interventions. Edited by curator and art historian Anita N. Bateman and architect and professor Emanuel Admassu, it explores representations of the continent—who gets to make them, how they circulate, what they mean. As you’ll read below, answering these questions requires addressing broad, complicated historical forces like colonialism, globalization, and economic power. The book testifies to the deep wellspring of creativity and thinking taking place across the continent and in the African diaspora. At the same time, because many of its interviews were conducted before 2020, Where Is Africa is also a useful tool for measuring the developments of these messy last few years.

Next weekend, the Center for Art, Research, and Alliances in New York, which published Where Is Africa, is hosting a free three-day program of talks and performances to celebrate the book’s release. If you’re near the city, I recommend attending.

Love all ways,

Brian

Brian Sholis: The earliest interview for this book took place in October 2017. Can you talk about how your idea of the book changed as it wound its way toward completion?

Anita N. Bateman: First, the book wasn’t always meant to be a book. Emanuel and I wanted to convene people on the continent to have in-person conversations that would bring synergy between people we admired. But so much has changed. We’re in a world now shaped by COVID. Our thinking has changed along with it, and the emerging artists and thinkers we interviewed are now much more established. They’re at the forefront of conversations about African identity, about cultural institutions, about creativity.

Emanuel Admassu: The aesthetic influence of Africa and the diaspora has been widely recognized; there hasn’t been enough conversation about what it means to do a project like this book on the African continent itself. Our initial ambition, as Anita mentioned, was a three-day convening in Dar es Salaam. Institutional and budgetary constraints kept it from happening, and we hit upon the book form when trying to work around those constraints. We want this book to be accessible to people on the continent.

There’s also a certain formality associated with this type of project. Rather than be too scholarly, we wanted to catch people and their practices where they were, then treat the resulting transcripts as a kind of archive. It will be fascinating, when we gather in New York, to see how people position themselves in relation to a documented conversation from six years earlier. What will it mean to reconsider interviews that explicitly critique institutional systems and the trajectories of colonialism?

BS: The book has divergent impulses with regard to community and geography: your interviewees talk about local networks, about cross-continental partnerships, and about international and diasporic connections. How did your own thinking about the relationships between your hometowns, the places where you now live, and these African capitals change? How do you reflect upon your own positions?

ANB: We started the project at RISD when we were both there, and it grew out of our active and distinct networks. Early conversations made it clear that we had to expand our efforts, to meaningfully address the ideas about global interconnection that started cropping up almost immediately. Everyone affiliated with the book continues to bounce around; Emanuel’s now at Columbia, I’m in Houston, and many of our contributors have moved on from the places where we spoke with them or invited their participation. These layers get added to the questions we ask but I’m not sure if the core is necessarily changing …

EA: I will say, though, that Anita was already an active art historian and curator when we began this project. I was in a different place: frustrated with architectural discourse’s inability to engage with Blackness, with the African continent. For me, these conversations were an opportunity to escape what felt like enclosure. These conversations have changed my work as a teacher and a practitioner. It’s been liberating to have my thinking opened up by the ideas generated from the making of this book.

BS: I want to push this point about local, regional, and international contexts a little more because two comments stuck out in my mind. Rebecca Corey said she saw the art center where she worked in Tanzania as “a space not of exposure but of protection,” about obscuring as a necessary part of what it could do for artists. On the other hand, Rakeb Sile said that London felt like the epicenter of contemporary African art discourse.

ANB: My intuitive sense is that’s comparing apples and oranges: someone who worked in a nonprofit, advocating for artists outside of commercial spaces, versus someone who is deliberately bringing African artists into the broader “art world” marketing machine. That speaks to certain ongoing tensions between colonial “centers” and metropolitan “satellites.” That it’s London and not some other city is a result of colonial dynamics, of course.

EA: I’ll add that we wanted to make a book that represents the political orientations and value systems currently shaping African and Africa diasporic art.

BS: These questions are also shaped by money—so many of the interviewees talk about fundraising challenges, about the overt or subtle influences that accompany money from elsewhere …

ANB: You can’t have these conversations about culture without funding being part of them.

BS: Several of the interviews talk about the unintended consequences of big political revolutions, and I want to narrow down the context to existing arts institutions and ask how you feel about revolution versus gradual evolution …

ANB: I’ll simply say that some people think art museums, for example, are beyond repair—their colonial origins make them irreparable. Certainly large institutions have legacies that make it harder for them to do even small things; perhaps newer or smaller institutions can be more nimble. I don’t think our signature institutions can revolutionize themselves; but when does a lot of patient, painstaking evolution become a revolution?

EA: I would also say it’s important to make sure that evolution doesn’t become mere reform. We don’t want change to legitimize institutions, to underscore existing hierarchies, to just make them slightly less violent. We’re interested in revolutionary imaginations that serve to challenge and transform everyday environments. As long as we aren’t complacent, we can move through big institutions and do work that is extremely productive. How can we leverage an obsession with relevance to open up spaces for other forms of conversation, other forms of relation, that we want to see?

BS: In the West, or the global North, when we’re trying to extend a conversation about artists and arts institutions into the realm of architecture and urban form, the word gentrification often comes up. In this book it appears only once, in passing. So what, to your mind, is the relationship between art-making and urban change in the African cities where you’ve spent time?

EA: The co-morbidities of art and real-estate speculation are so explicit in the West. In the two African cities I’m most familiar with, Dar es Salaam and Addis Ababa, the dynamic of art-led gentrification is less present, and perhaps it’s because art isn’t seen as an “investment” opportunity. A group of artists living and working in an affordable neighborhood aren’t necessarily as able to generate the kind of interest and investment as they are in the West. That’s changing as contemporary African art increases in value and as international artists establish centers on the continent.

Instead, what I see is investment speculation around multi-family residential projects by people in the diaspora. Money is being funneled directly into concrete in a way that isn’t just “follow the artists.” There are museums like ZOMA, really transformative spaces that are legible to a global community, that might begin to have that impact.

BS: The book points out that Dar es Salaam and Addis Ababa are two of the African capitals that had less direct encounters with European colonialism in the twentieth century. Do you think that a relative lack of European presence then means that these cities, in the twenty-first century, might be less likely to follow typically European and North American forms of urban development?

EA: That sounds plausible to me. Even comparing the two cities, Dar es Salaam registered the colonial influence more than Addis, and today you can see more clearly the European and North American cultural influences in Tanzania than in Ethiopia, which remains more cloistered. And when you consider other cities that were sites of direct colonial intervention, how that shapes urban form is even more explicit.

But it’s all changing rapidly, especially in Ethiopia, where the orientation now is toward the Middle East and China. Ethiopia isn’t unique in that, and these geopolitical realignments are causing a lot of anxiety in Europe, where political and urban thinkers are very aware of Chinese interventions in Africa.

BS: Given that reality, I also noticed that the word China only appears once, too. That could be a result of how recently the reorientation you describe began, and how the book’s interviews took place six or seven years ago. And I can’t help but wonder how the Chinese investment in African infrastructure will affect African cultural forms …

EA: The Chinese interventions are very focused on development, whereas Euro-American interventions still include an aspect of classification, an attempt to pin down these cultures and fit them into a universal project. That interest can lead, among other things, to more funding for the arts. Thus far the Chinese impact is massive but focused on construction, infrastructure, mass transit. They’re producing containers but the content, so to speak, is yet to be determined. So far, it’s a different mindset. It could be a way to have influence without getting mired in politics: most everyone will agree to getting a train line built, but as soon as you build a museum to tell the origin story of, say, Ethiopia, there’s going to be a lot of disagreement.

A dominant East African perspective, after the secularization process, has been infrastructural development. The political and economic elite treat it like a religion, and the Chinese intervention seems to address that directly. None of this, of course, is static; everything is updating in real time.

BS: I couldn’t help but notice one of the book’s design choices emphasizes that sense of slipperiness. In the first third of the book, the word Africa is backslanted; in the middle it’s upright; and toward the end it’s italicized. It’s as if the word itself is slipping out of our grasp.

EA: We’re such huge fans of Nontsikelelo Mutiti’s work, and we wanted to make sure the book’s design is in line with the questions we’re asking interviewees and are being addressed by the included artworks. From the beginning Mutiti had ideas about multiple orientations and counter cartographies as they relate to a name that itself was not created by Africans. The dynamism of the device you mention is in line with the sensibility we have, with our understanding of Africa itself.