Values Proposition

Frontier’s founder on the continuing relevance and value of Design Thinking

In a new blog post, designer, educator, and writer Jarrett Fuller suggests that a spate of recent articles have come to a similar conclusion: that Design Thinking, as developed by IDEO in the 1980s and ’90s, “doesn’t really work …. [and], as a standardized process, consistently produces ‘solutions’ that just actually aren’t that innovative, exciting, [or] culturally significant. What design thinking does is pad the pockets of the corporations employing these processes.” Fuller labels this “corporation-centered design” (as opposed to IDEO’s “user-centered design”) and contrasts it with an idea, borrowed from Dan Hill, of the designer as a cultural inventor.

A lot of what Fuller writes resonates with me. At the same time, I think critiquing the idea of Design Thinking is a bit like critiquing the idea of the scientific method. When co-opted for profit-driven motives, of course it becomes a problem. But it remains a valuable process when used in the right way for the right reasons. I think it is still a much better model than the kind of consulting suffused with the logic of business-school value creation, which starts with profit, rather than better human experiences, as the primary motive.

That said, the term design thinking is definitely overused. Cultural invention is a good way to rethink it. So much of the work we did in the early Bruce Mau Design days was posited as “the culture of …”: The Culture of Work, The Culture of Sport, The Culture of Technology, and so on. What all that work had in common, in my view, was a desire to bring intuition, emotion, and holistic thinking into a world dominated for at least a century by linear, scientific methods of thinking. BMD spoke often about crossing boundaries; the studio even built an educational program, the Institute Without Boundaries, around the idea. The best design has always been about allowing emotion and messiness—you know, humanity—to enter into conversations in more structured ways.

Perhaps that’s why design’s halo has faded somewhat in corporate America. There is nothing predictable about it. Design Thinking can never guarantee the desired outcomes in a corporate project, especially once the methodology came to be associated with one-off phenomena like the iPhone. There is a reason why the largest design company in the world has about seven hundred people on staff: creativity, intuition, and emotion are not commodities and do not scale. You can set the stage for the arrival of a breakthrough insight that leads to a new product, like the iPhone, but, again, you cannot guarantee it.

Even if you have the insight, you need the perfect environment for it to succeed—and much of that environment is outside the control of a designed process. Unfortunately, the world we live in tends to erase risk: breakthrough innovations only happen when there’s a dogged will and the ideal cultural, environmental, and economic circumstances to foster them.

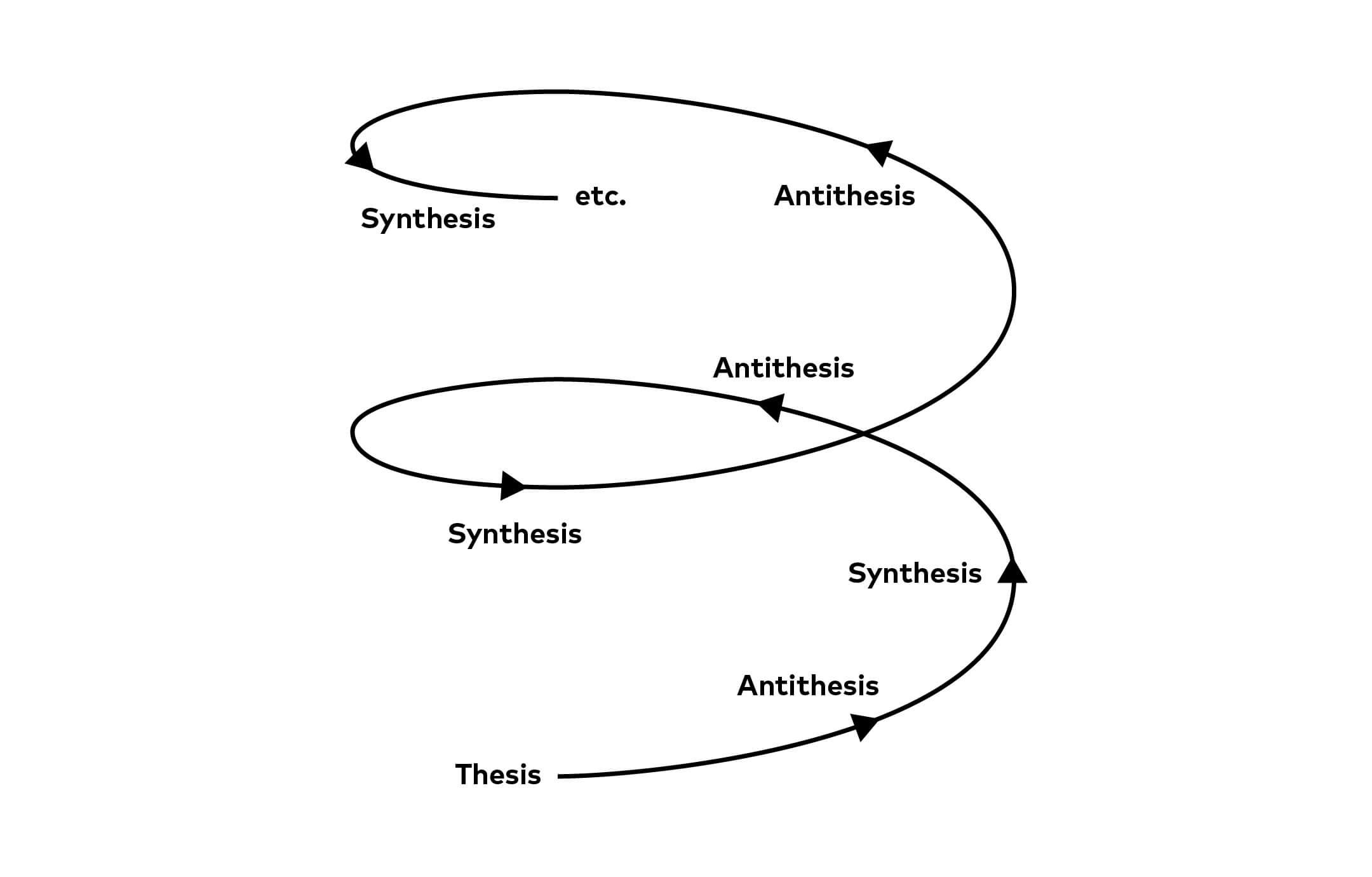

Design as a process, and Design Thinking more specifically, are now fully mainstream. But they are (hopefully) in the late-antithesis phase of the Hegelian dialectic. Some organizations have committed to it—Mauro Porcini is still head of design at PepsiCo—and understand it’s not a silver bullet, not a unicorn factory. At present, most companies still require design authors because being able to ascribe responsibility is the most effective way for risk-averse organizations to accept the unpredictability that design requires. (And, taking it a step further, the people inside organizations who hire designers can point to the reputations of famous designers as a way to help manage the risk associated with the design process.) If anything, the wilder the design author’s voice, the higher likelihood they will reach notoriety—and influence—because people expect some quirkiness from their design leader. Just think of the clichéd round glasses or jeans and a blazer in a room full of suits.

The Hegelian process I mentioned begins with a thesis (in this case design thinking), proceeds to antithesis, and ends with synthesis, something that unifies the first two phases. Fuller’s thought-provoking blog post is part of a broader unresolved conversation in our industry, one that I look forward to both following and contributing to in the coming years.