What is a Brand?

And what is it not?

In 1876, Bass & Co’s Pale Ale was trademarked in the United Kingdom. Its red-triangle logo was the first registered trademark under the new Trade Marks Registration Act of 1875.

That logo is considered to be the first brand, in the modern sense. But the concept of branding goes back further. The word brand comes from the Old Norse word brandr which means “a burning” or “fire.” In Norse poetry, brandr was a poetic word for sword and was a play on fiery brilliance and destructive power.

By the sixteenth century, brand came to mean a mark burned on cattle to show ownership, but the earlier meaning serves better as a way to describe the modern associations with the word.

Most people still think about a brand as a logo. Coming from the world of architecture, I’ve experienced the many negative associations with the word. Usually the brand is the corporate sign that gets “stuck on” a building. It’s all surface, and it sullies the building’s design.

I’ve come to learn, over the last twenty years, that a brand is so much more than the logo. It’s the associations, values, and personality tied to an organization. It sets direction, aligns those within, and creates the ambition that gets the organization where it is headed. When approached with care, the brand is the core of what any enterprise undertakes. When approached carelessly, it’s superficial marketing.

Even architects have recognized this evolution in the understanding of brand. With the help of people like Marty Neumeier, some are quick to point out that a brand is not what you tell your audience you are, it’s how they perceive you and what they say you are. But his iconic books, "The Brand Gap" and "Zag, are 20 years old and the richness of brand thinking has only deepened since then. So much has changed and brands have become much more than even reputation or customer perception.

Here’s what I’ve learned.

Brand is Story is Brand

If a brand is the set of associations, values, and personality tied to an organization or product, then it’s essentially a story. But more than an after-the-fact bedtime tale, it can be the fundamental, strategic, consolidated description of who you are.

A story can be composed of several elements: purpose, ambition, guiding principles, tone, and more. But at its core, a story is simple, and offers a narrative point of view. One common way to think about a brand is through the lens of Jungian archetypes. These 'primitive mental images', supposedly present for all of us in the collective unconscious provide a simple frame of reference that helps add dimension to a brand.

Muji is the story of the non-brand brand without clutter and focused only on what’s essential. The narrative is Japanese minimalism as an antidote to consumer excess, and the archetype is the Innocent.

Monocle’s story is that of a well-designed life—at home, work, and abroad. Its narrative is modern globalism as a lifestyle, with high taste and cosmopolitan optimism, and its archetypes are the Sage and Explorer.

With these starting points, it’s easy to imagine how the entire worlds of those companies come to life, including things like the architecture they create. They offer the DNA, the road map, and the vision that guides everything, from hiring to products to how they communicate.

A Brand Is a Living System, Not a Static Logo

Ultimately, a brand is evaluated based on the entirety of the experience it offers. A logo, at best, is the distilled symbol of the enterprise. At worse, it’s an exercise in trends and shape making.

Recently, I had a conversation with the architect for a new series of highway service centres, called ONRoutes, that we were both involved with years ago. They described how, up to that point, they’d thought about the branding as the logo and nothing else. It was through the process of creating the brand (or story) that the full potential revealed itself.

Even before the project started, we had to win it. Our team developed a proposal for the project in collaboration with the lead developer that focused on the challenges with highway service centres and redefined what they could be. One guiding idea was that, previous to this new project, they’d been generic buildings at some innocuous location along the highway. We recommended that the concept should centre on place in a more local way. Why could the centres not point to adjacent communities?

Our proposal succeeded, and the project started in earnest. The senior design lead on the project, Carolina Soderholm, came up with the name ONRoute. It was a great idea because it solved a few strategic issues and it told a story. The brand had to work in English and French, had to somehow tie to the geography of Ontario, and infer what the brand was all about. With the play on the words en route, we accomplished all the goals in a neat package.

Next we moved onto a visual identity. That work included not only the graphic system that would result in a logo, but it also explored ways that the new centres could encapsulate place in a more specific and relevant way. A big part of our approach included telling the story of the community near each centre; we included nearby community names into each service centre so that each became a waypoint for the visitor journey.

Then we moved to signage and wayfinding. Taking cues from the architecture, we designed a system that helped drivers easily recognize the stops along the highway and even used highway road-sign material in the building signage to create a tie to the journey itself.

These layers add up to what we define as the brand. Of course, it also includes things like how clean the washrooms are kept and what food options are available and, unfortunately, it’s rare that the originating vision is strong enough that it resists the pressures of the bottom line. But without that strong initial vision, there is no hope of a consistent brand experience.

Nothing Without Execution

It’s one thing to have a great idea. It’s another to deliver it in its best possible form. This step divides good from great and is why I feel that design, as a discipline, will endure through the oncoming avalanche of AI slop.

Today, nothing stops you from designing anything. But what separates bad from good from great design is a combination of experience, skill, and understanding. Designers who have spent most of their lives making things are will better understand how to make things that stand out. The explosion of tools like Sora, Midjourney, and Runway are democratizing design and creativity in powerful ways. One result is that many people will lose their jobs.

But new tools are not new phenomena. They simply tend to raise the bar for what we can consider to be quality. The technology is not the breakthrough worth paying attention to. The idea still matters, and the careful attention to execution separates good from great.

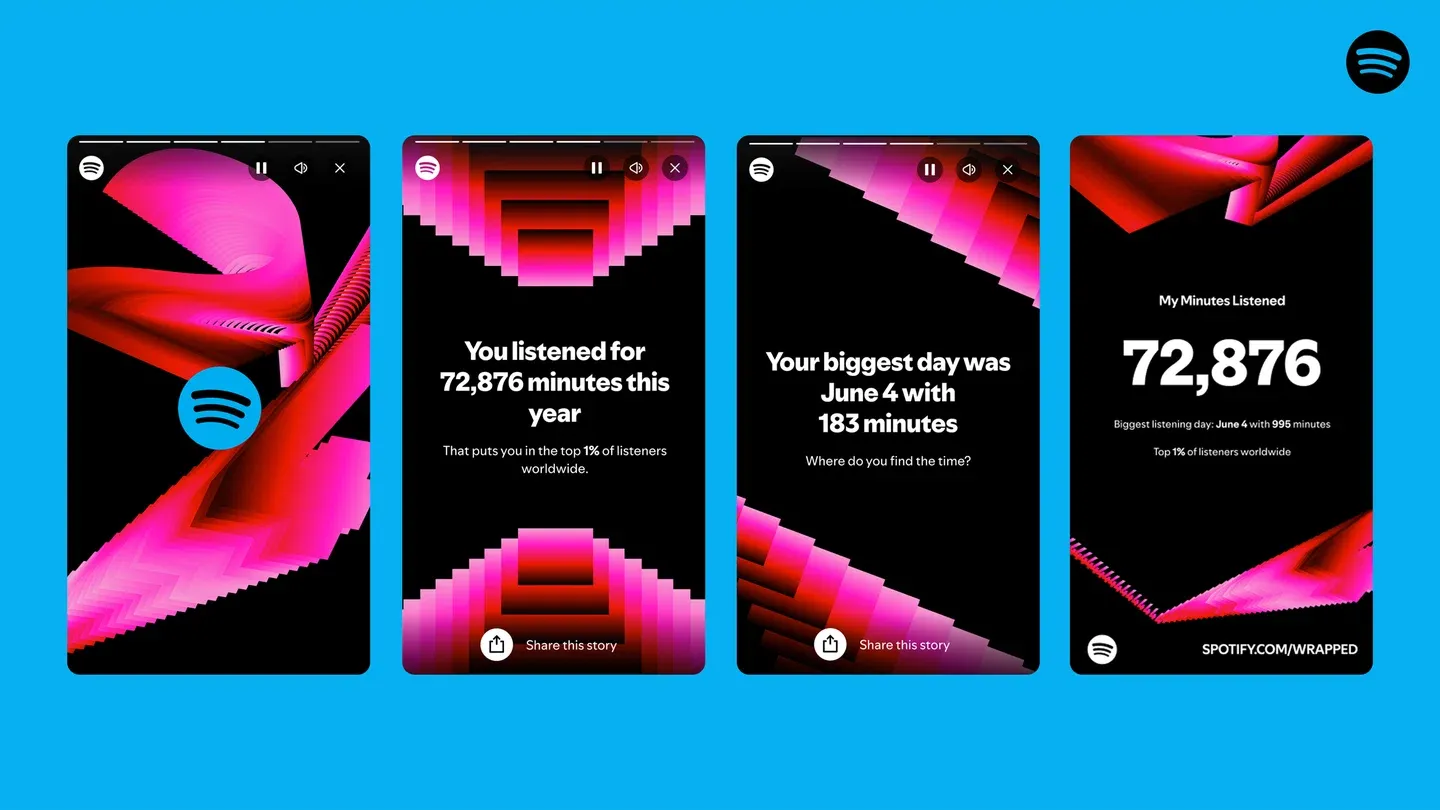

For example, it’s not that iTunes users couldn’t access the data that reflected their music habits. They just had to dig through menus or sign up for third-party tools to access it. Spotify turned user data into an experience. Through vibrant design and animation, it created the idea of “Spotify Wrapped”: socially shareable stories and personalized visuals that are so powerful that they’ve become a year-end social -media ritual.

The execution of Spotify Wrapped helped it succeed.

This same thinking applies everywhere else. The more we see the latent opportunity in our environment that we usually take for granted, the more we are realizing the full potential of our brand.

Branding started as a way to distinguish a product from the competition through the simple act of applying a logo. It has evolved to become a way that organizations create complete experiences delivering their essential story to people who engage with them in unforgettable and genuinely enjoyable ways.

All it takes is understanding and mapping out the experience you are trying to create, building it in a way that becomes multi-dimensional, and executing in a way that separates it from the slop.

Easy, right?

🤯 Matt Zein

👨🏽💻 Experiments in Dynamic Brands (Courtesy of Brian Sholis)

🏍️ Eames by Enso