When Stories Change the Future

How a documentary changed the course of a small island off the coast of Newfoundland

When I moved from Newfoundland in 1989, it was against the backdrop of a collapsing fishing industry. My father, a journalist, had spent several years hosting a television show called Land and Sea and had traveled all over the island and seen the impacts firsthand. There were many stories of loss, with some scattered tales of resilience and success in the face of the collapse.

Beginning in the 1960s, “Factory Boats,” with massive nets that dragged the ocean floor and scooped up both fish and elements of their habitat, devastated what had been the livelihood of Newfoundlanders for centuries. Little did they know, but the “inshore” fishery and its practices, which included things like hand-line fishing, had been a sustainable practice that was now obsolete because of the new industrialized and large-scale fishery.

Consequently, small fishing villages throughout Newfoundland suffered. Some people left the communities where their families had lived for generations. Others had to find other means of living. In another feature of Newfoundland culture, communities, despite their close proximity, had been traditionally isolated from one another; distrust and skepticism of outsiders contributed further to a sense of fragmentation. The resulting lack of leadership prevented unified resistance to the problems they did not even know they shared.

One result was a resettlement program. The government began consolidating communities under the logic of economic efficiency. In many instances, outport communities were literally moved across the water and joined together.

Meanwhile, in St. John’s, the capital of Newfoundland, Donald Snowden of the Memorial University of Newfoundland led something called the Extension Services. Not a traditional academic outreach program, it saw communication as action rather than simply education. The mission was to give people the tools to analyze their situation, express it clearly, and act. Snowden partnered with the National Film Board of Canada under its Challenge for Change program to deploy film as a community-development tool. The program spanned all of Canada, but one site of focus was Fogo Island. Located just off the Northern coast of Newfoundland, Fogo represented an opportunity to apply film as a tool. Its eleven distinct communities were primarily small fishing settlements, some with Irish Catholic heritage, others with English or other European roots. At the time, many faced economic hardship due to the decline in the inshore cod fishery, leading to pressure from the Canadian government to relocate under the resettlement program.

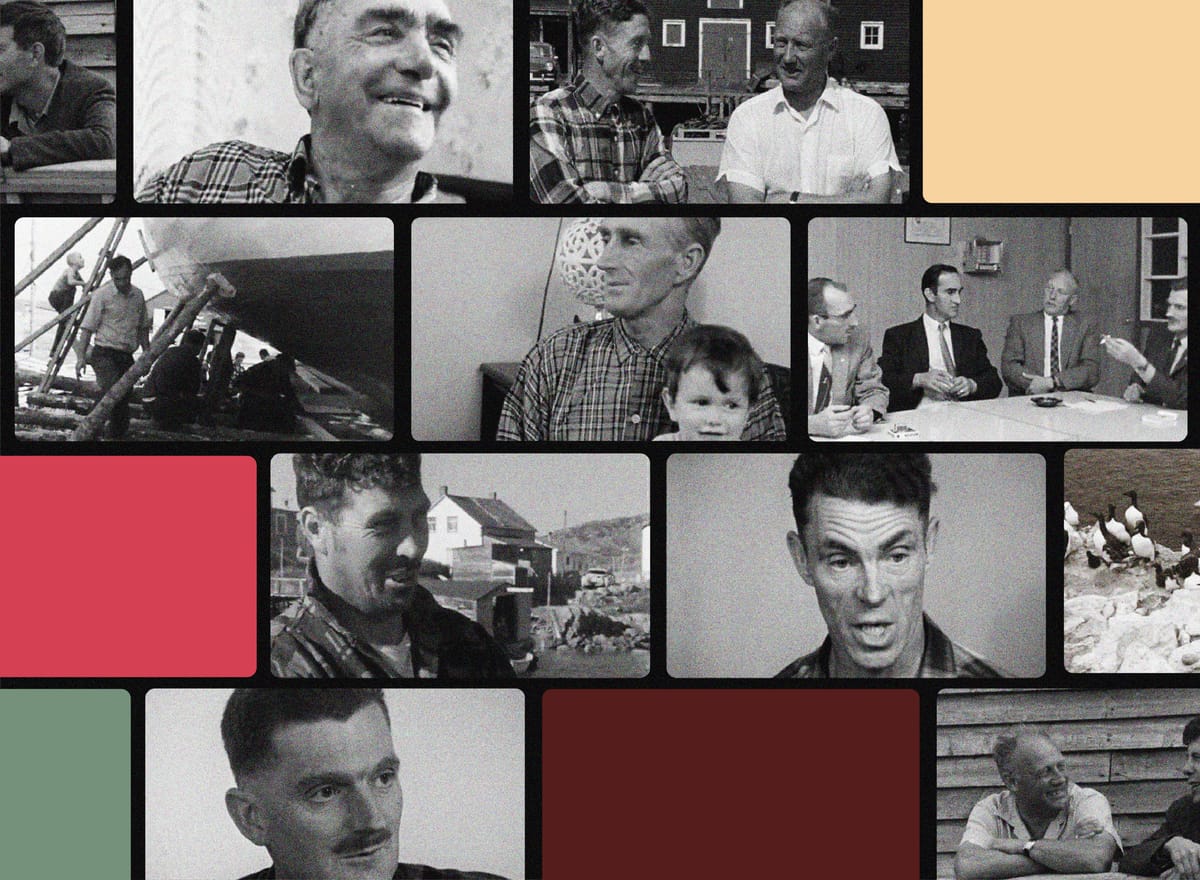

Filmmaker Colin Low and the NFB recorded interviews with fishers, families, clergy, and youth, capturing their perspectives on resettlement and survival. But rather than a traditional documentary film practice involving a narrator and a purely observational point of view, the twenty-seven films they produced were not about Fogo Island. Instead, they were made with the people who called it home.

Once completed, the short films were shown immediately to the community, who gathered, discussed, and evolved their thinking together. These communities, so used to isolation from one another, were surprised to see they shared a common set of issues.

The same films were then shown to government officials—inverting the traditional flow of communication. The result was a set of community cooperatives including the Fogo Island Co-op. Because of the newfound collective alignment and planning, the government backed off the resettlement plan and a new precedent was born: communication as infrastructure for community transformation.

Communication as Transformation

These films did more than simply document a place and time, and they were not focused on persuasion. They were about visibility: people seeing themselves, and each other, more clearly.

Storytelling, in this case, was an act of coordination. The films served as shared reference points that unified fragmented voices. By seeing themselves—and seeing themselves in each other—they could act with confidence and combine their individual voices into a more forceful whole.

Nor were these documentaries cold and abstract reports of the facts. They were personal, tied to identity and place. They were emotionally anchored narratives.

They also served to bridge the gap between lived experience and government policy-making because they were shared with both the communities and the elected officials making decisions about their future.

The Science of Emotion and Narrative

Such narratives and emotional storytelling can support strategic goals. When combined with strong rational case-making, communication can catalyze profound change.

Meaning & Memory

The value of meaning and memory in communication can be hard to quantify but both are anchored in emotion. A key struggle in strategy work is embedding them in the minds of the people tasked to execute. A 2004 study demonstrated how activation of the amygdala enhances memory for emotionally significant events. Emotionally grounded messages stick in ways that those relying on reason alone do not. For the people of Fogo Island, seeing and hearing the stories of others who shared the same challenges they did was a powerful impetus for change.

Neural Coupling

A 2012 study demonstrated that when we hear stories, they activate a process called neural coupling. During the act of storytelling, the speaker’s and listener’s brain activities synchronize across the regions responsible for emotion and comprehension in a process called neural entrainment. By simply telling one another stories, we close the distance between us and become, literally, more aligned. With the Challenge for Change program, this phenomenon was achieved through film with the critical insight that more alignment would mean more co-operation.

Organizational Decision-Making

A 2015 study demonstrated that emotions like fear, anger, or compassion bias risk perception and strategic choices more often than data or logic. While we must always endeavour to apply reason to our decision-making, we must also acknowledge the critical role that emotion makes when we finally come to our decisions. Narrative is a powerful tool to engender that emotion, and while rational messaging is the foundation and bedrock of organizational decision-making, storytelling that resonates emotionally and reflects identity is the fuel. Again, seeing other communities experiencing the same struggles resulted in cooperation among the people of Fogo Island and the establishment of the Fogo Island Co-op, which provided an uncommon social and economic resiliency for the island in subsequent decades.

A Healthier Story

In 2013, the Cleveland Clinic released a four-minute internal film called Empathy: The Human Connection to Patient Care. It featured a silent montage of patients, staff, and visitors with captions showing their unspoken struggles.

The Human Connection to Patient Care. Courtesy of Cleveland Clinic

At the time, the organization was suffering from an internal culture known for clinical excellence but emotional distance. They’d established a goal to become more rooted in compassion and holistic care. With this objective, they made the film. But the film wasn’t made for patients; it was instead shown at internal staff events, onboarding sessions, and leadership meetings.

A recent episode of the excellent podcast Hidden Brain mirrors this idea in its discussion of how the practice of narrative psychology centres on the idea that the stories we tell ourselves shape who we are and how that understanding becomes a strong mechanism for behavioural change. When healthcare workers reframe their internal narratives from “task-completer” to “healer,” their behaviour toward patients shifts.

The film acted as a narrative intervention—it gave staff a new, emotionally resonant lens to interpret daily interactions, and the results showed the impact of the tool. Patient satisfaction scores increased in communication and care domains, rising from 63 to 77 percent over three years. Employee retention improved as organizational identity became more purpose-driven. It began to shape internal identity, with staff began referring to it in training and even during shift changes. Finally, the film went viral beyond the institution with over ten million views.

Ultimately, the film helped staff “re-story” their professional identities from overwhelmed workers in a bureaucracy to caregivers who matter and can make a real difference in people’s lives. It activated core principles of narrative psychology, including the idea that identity is constructed through the stories we tell, that these stories can be edited through emotionally significant interventions, and that new stories can lead to new behaviours.

Need to Have

We often think of stories as “after-the-fact” and “nice-to-have.” We also tend to associate them with entertainment or advertising. When embedded structurally and strategically, however, stories improve alignment, culture, and outcomes. Far more than simply shifting how an organization is perceived, powerful stories shift how they perform.

This is the basis of exceptional branding. Sure, there’s the obvious fact that a good brand is not what you say about yourself but what others say about you. But far more important and meaningful is the idea that a good brand starts with a c0-created and well-told story about what you and your organization have the potential to be.