Dynamic Duos

On two films at this year’s Architecture and Design Film Festival

Hi everyone,

It’s that special time of year when there are more events to attend than hours in the day. Next week is shaping up to be particularly busy for Torontonians interested in art and design. There is Azure magazine’s Human/Nature conference, the latest edition of the Art Toronto art fair, and this year’s Architecture and Design Film Festival. Plus, Frontier Magazine podcast guest Deb Chachra is delivering the Fred Kan Distinguished Lecture at the University of Toronto. Phew! So I screened two ADFF films about creative partnerships in advance, and you’ll find notes on them below.

Elsewhere, New York magazine ran an adapted version of the essay we at Frontier commissioned from critic Justin Davidson for Set Pieces, the new book from Diamond Schmitt Architects. Read the essay here, and read my behind-the-scenes account of making the book here.

Have the day you deserve,

Brian

🔗️ Good links

- 🏢👀 Buildings that caught my eye this week: Sam Jacob Studio’s 2022 residence and community center in London; a229 and evr-architecten’s waste-sorting facility in north Brussels; this sustainable Australian residential retrofit by The Sociable Weaver; and this dramatic urban house in Osaka, by Hayato Komatsu Architects

- 🇲🇽🌳 Celebrated artist Gabriel Orozco, a personal favorite, has led the redesign of Chapultepec Forest, a park in the center of Mexico City

- 👂🏻🌃 “Across 10 years, Max Neuhaus performed Listen 15 times, eventually stripping the work down to its critical elements: ‘Saying nothing, I would simply concentrate on listening and start walking.’”

- 🐌🌱 Friend of FM Patrick Pittman on how “botanic gardens around the world are now attempting to untangle the legacies of empire.”

- 🎙️🏚️ A brief interview with Christopher Brown about his new book A Natural History of Empty Lots

Double Dutch

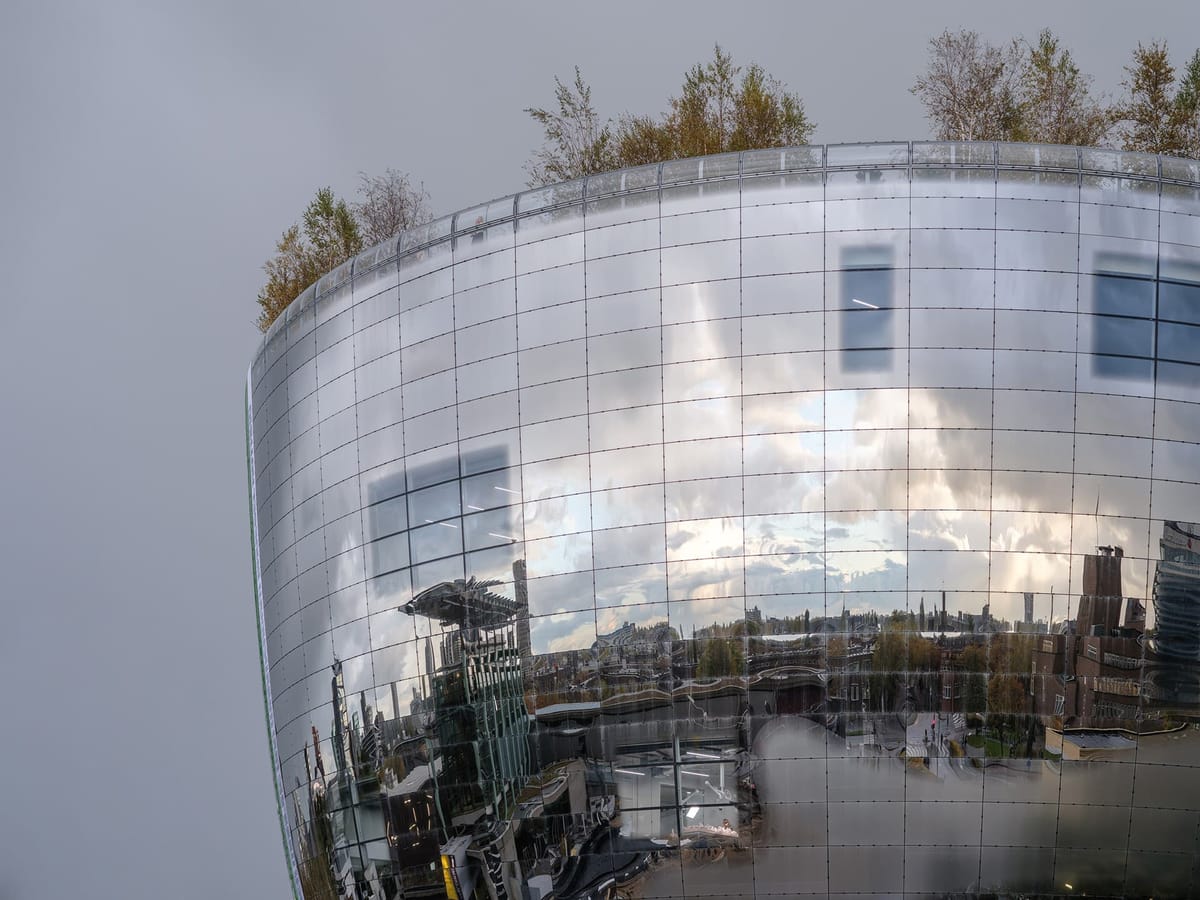

In the course of this documentary, architect Winy Maas refers to the Depot Boijmans Van Beuningen, in Rotterdam, as “a sort of prison, but also a beehive,” a refrigerator, a disco ball, and a spaceship. He describes it as stubborn, and suggests that it “shouldn’t look like anything.” (I took him to mean it shouldn’t look like other buildings, such as the “flat pancake by Rem Koolhaas” nearby.) To further suggest the project’s distinctiveness, he adds, in reference to its reflective exterior, “It’s not a building, it’s a part of the city.”

Maas, a founding partner of the Dutch firm MVRDV, is one of filmmaker Sonia Herman Dolz’s two “visionary minds.” The other is Sjarel Ex, the longtime director of the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, who commissions Maas to design a “depot” to make the museum’s 150,000 objects publicly accessible. The problem they’re solving is made clear at the outset of her film: the museum’s 1935 building didn’t account for the growth of the collection, and is riddled with leaks and asbestos.

What’s also made clear is their alignment. Maas and Ex are both about sixty, both leaders in their fields, both willing to act a bit silly to deflate the aura of pretension as they go about their unusual work. We only see hints of how Maas’s design proposal rubs people the wrong way: footage from a state-council meeting wherein “experts” state objections to plopping a big reflective orb in the middle of a city park. Otherwise, the problems overcome in the film are largely technical: how to pack and store the art, for example, or how to apply the large mirrored-glass panels to the building’s exterior, crane its enormous staircases into place, and get the mature trees onto its roof.

These challenges are interspersed with fascinating footage revealing how a museum really works: its back-of-house spaces; de-installing, packing, shipping, and re-installing artworks; the late-night laptop work Pipilotti Rist does with assistants as she tweaks her outdoor video installation. We see Maurizio Cattelan’s sculptural self-portrait removed from its hole in the floor, several Mondrians lifted into and out of crates; and a Kusama “infinity room” being deinstalled. If you’re a fan of the meme account @the_art_of_installation, there’s a lot to love in this movie.

The torrents of Maas and Ex’s conversation might be a little off-putting if what they had accomplished, together with others given cameo appearances, were not so remarkable. They marshaled nearly 100 million Euros to create not only a dramatic piece of architecture, but also, as Ex notes, “a new typology of museum building.” There has been a trend toward “open storage” in the museum world for some time—see the American wing at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art for one prominent example—but the Depot in Rotterdam goes further, admirably placing even greater emphasis on public access.

One our chief protagonists describes the Depot as “a building in which Rotterdam contemplates itself.” This film, too, is a useful and broadly accurate reflection of the labor it takes to create a new kind of museum space—one premised on what Ex describes as “quality but eccentricity.”

Depot: Reflecting Boijmans screens in Toronto on October 24 at 9:00. Learn more, watch the trailer, and buy tickets here.

Character Sketches

In London in 1976, architect and theorist Léon Krier lashed out at Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown from his seat in the audience at one of their talks. He laments the wave of American Pop art and neon signage about to wash over European public spaces, and suggests that the Philadelphia-based architects are partly to blame. Venturi’s cool response? “That’s your problem. I’m really sorry about that.”

The interaction, included in director Jim Venturi’s entertaining biopic about his parents, encapsulates much about what upset people about the couple. It demonstrates their willingness as designers to embrace, rather than try to impose strict order upon, what they saw around them. And it shows how their wry humor could seem, at times, like dismissiveness.

Stardust does a good job of outlining the twists and turns of their long careers. It ranges from Venturi’s relationship to Louis Kahn at the University of Pennsylvania and Scott Brown’s embrace of Los Angeles and Las Vegas, leading to their landmark collaboration with Steven Izenour, Learning from Las Vegas. It touches on early projects, built and unbuilt, including the house Venturi designed for his mother; proceeds to their 1991 building for the National Gallery of London, the subject of more controversy; and includes the couple’s reflections on career fortunes that waxed and waned with the public’s changing tastes. “We were the last to know we were out of fashion,” Scott Brown says at one point.

But the film’s real strength is suggested by its subtitle: “The Story of Robert Venturi & Denise Scott Brown.” I appreciated its glimpses of the contours of their relationship—how they riffed for each other, since “play can be very holy”; how they each responded to the places, frequently in Italy, where they traveled. They discuss what it was like to live in his mother’s house soon after their marriage, and we also see them watching TV together in their own home. She recalls how he cried when she told him the story of her first husband’s death, and how that reaction “healed” her. Later, she admits that “he has some southern Italian opera in him.” His observations about her character are less frequent, but his love for and appreciation of her are evident throughout.

In recent decades, and especially since Venturi’s death in 2018, scholars have paid closer attention to the contributions Scott Brown made to their shared output. (The Pritzker Prize committee famously omitted her name when giving him the prestigious award in 1991.) Stardust shies away from neither this effort nor, as his memory failed late in life, Venturi’s occasional lapses to credit her as he discussed their work.

Late in the film, Scott Brown muses about how the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s were a particularly difficult period for women with professional ambitions. This was true in architecture, as Stardust makes clear by portraying late-modern architects like Philip Johnson as villains unwilling to take them, and especially her, seriously. She then wonders aloud, “Maybe if I hadn’t been around [Venturi], I wouldn’t have gotten the chances I did.”

There’s painful truth in the statement. But not long after she says this, during the closing credits, they’re seen back in Las Vegas, wandering with tourists beneath a barrel vault entirely covered in LED screens. He covers his ears and asks about a rock song being piped in. She, still irrepressible in her eighties, IDs the track and bops along to its beat.

Stardust screens in Toronto on October 24 and 26 at 6:15 p.m. Learn more, watch the trailer, and buy tickets here.

More from Frontier Magazine

- Six months ago: An interview with programmer Jake Dow-Smith on the web’s needless complexity and translating signals from one medium to another

- One year ago: An interview with writer and engineering professor Deb Chachra on infrastructure as “care at scale” and our abundant-energy future

- Eighteen months ago: “bettering the built environment requires architects and non-architects to come closer together in their efforts.”